September 22, 2020

Contact: Eric Stann, 573-882-3346, StannE@missouri.edu

Left or right. Among other uses, these terms can generally identify most Americans’ political beliefs — liberal or conservative, Democrat or Republican. When these views are at the extreme ends of the political spectrum, they are known as political polarization. With the gap between these political ideologies in American politics growing wider, experts argue that the gap between both sides is threatening the health of America’s democratic system of government.

However, up to this point little has been done in proposing a solution to help decrease this political animosity. Now, communication experts at the University of Missouri have recently developed a narrative writing exercise designed to encourage people to reduce their political polarization.

“When people become politically polarized, they are unable to understand the people who are politically different from them, so they tend to make up reasons for why they are in disagreement,” said Ben R. Warner, an associate professor of communication at MU’s College of Arts and Science and co-director of MU’s Political Communication Institute. “It’s rooted in a belief that similarly minded people are motivated by benevolence, while those from the other group are motivated by malevolence. When that happens, the stakes of winning and losing in politics are too high, and it becomes impossible for people to cooperate with others who are politically opposite. This belief system can also lead to negative thoughts about democracy as a viable form of government.”

For Warner, the encouragement to reduce political polarization needs to happen early on in life.

“For most people, their political socialization occurs sometime between the ages of 16 – 22,” Warner said. “So, this is the prime time to reach young people as their long-term political attitudes are forming.”

Warner’s self-described "obsession" with politics began early. After he joined his high school’s debate team, his interest in the study of communication began and continued into college. In graduate school, his debate team coaches encouraged him to study political communication, since the team was based in the communication department. This occurred during the rise of the internet in the early 2000s, and Warner, while optimistic that the internet would help foster a democratic culture, quickly learned it could also lead to political polarization. Despite this notion, his self-described obsession with politics continues today.

“It’s a puzzle,” Warner said of his passion for watching politics. “For example, I love watching people perform in the debates, and then seeing the reaction afterward from the media and the polls. I follow politics like some people follow their favorite pop culture, sports or hobbies. It’s entertaining. The higher the stakes, the more compelling the content.”

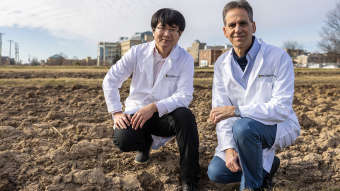

Warner reached out to two colleagues in MU’s Department of Communication to help create and test his exercise — Haley Kranstuber Horstman, an associate professor of communication at MU, and Cassandra Kearney, an assistant teaching professor of communication at MU. Horstman has experience using narrative writing in the context of health and family communication, and Kearney focuses on issues of communication and violence. Together, the researchers asked a group of 179 college students to test their theory.

First, each student was asked in an online survey to self-report their political beliefs. Using this information researchers could determine the following imaginary scenario — the student finds a hypothetical classmate’s Twitter profile, and upon reading six of their classmate’s tweets, discovers the classmate is strongly political with different beliefs than the student. The tweets were modeled after actual partisan tweets, and designed to provoke angst in the reader.

Upon rating the level of angst toward the author of the tweets, each participant was randomly assigned one of three types of narrative writing exercises:

- First-person perspective-taking: Describe a scene in which this hypothetical classmate was assigned to deliver a class presentation on an issue they cared deeply about in their favorite class. Something goes wrong with the presentation, and their classmate has to work creatively to salvage the project in order to get an A and pass the class.

- Cooperative contract: Participants were asked to write about a non-political task in which they cooperated with the author of the tweets, such as creating recruitment materials for Mizzou.

- Control: Participants were instructed to write a story about themselves rather than the author of the tweets.

At the end of the exercise, each participant was asked to re-evaluate their level of angst toward the author of the tweets. While other research studies on narrative writing have shown value for emotional and physical health, the researchers in this study also found narrative writing can reduce political polarization by fostering different perspectives and creating a sense of common identity.

“First, it forces people to think like someone they do not agree with,” Warner said. “I think when people disagree with someone, they tend to think of them like a caricature image, or as a one-dimensional character. But, when someone has to write about that person, the character develops depth. So, by all of a sudden getting inside someone else’s head like that, it’s hard to develop that caricature image.”

“Reducing political polarization through narrative writing,” was published in the Journal of Applied Communication Research.