George Massengale was 19 years old, soon to be a junior at Mizzou, when he found himself standing beside two Tiger track and field teammates at the precipice of immortality.

It was Aug. 20, 1920, and Massengale, BA 1922, was one of 288 athletes representing the United States in the Games of the VII Olympiad in Antwerp, Belgium. A native of St. Louis County, Massengale had barely left Missouri during the first two decades of his life. Yet here he was, in one of Europe’s ancient capitals, now at the center of the sporting universe.

Before a single race had been run, the University of Missouri had already made its mark by sending multiple athletes to the games for the first time in the modern Olympiad’s 24-year history. The only other Tiger Olympian had been hurdler John Nickolson, who traveled to Stockholm in 1912 and returned with a sixth-place finish. But in Jackson Scholz, BJ 1920; Brutus Hamilton, BA 1922; and Massengale, Mizzou had seemingly tripled its chances of finally bringing a medal back to Columbia.

This day was supposed to have been Massengale’s turn. It was the final of the men’s 200-meters, Massengale’s event, and it was a race he seemed built to win. He had only qualified fourth in the 200 for the U.S., but fellow Tiger Scholz, who had qualified first and held the U.S. record for the 220-yard dash, had pulled out of the event, spent from a tearful fourth-place finish in the 100-meters. Several other prominent runners were also absent from the day’s final. Perhaps most important, days of rain had transformed the hastily built track into a muddy slog, which tended to favor long-legged sprinters like the 6-foot-1 Massengale. But on the sea voyage across the Atlantic, the teen succumbed to AS, ankylosing spondylitis, a rare disease that causes swelling of the joints, and was forced to withdraw. “In the 1920s, they didn’t even know what it was,” says Massengale’s son Robert Massengale, BSF ’56, MS ’70. “They were staggered he could run at all.” Instead, Massengale was forced to stand on the sidelines and watch alternate Allen Woodring, a Pennsylvanian, take his lane.

It was a fitting end to what had been a harrowing journey for Massengale and his teammates. It had begun with the trans-Atlantic voyage aboard the Princess Matoika, which had just returned from Europe carrying the flag-draped coffins of 1,800 servicemen who had died in World War I. The VII Olympiad was the first games in eight years, due to the 1916 games having been canceled amid The Great War, and most of the U.S. athletes were too young to have served on the American Expeditionary Forces that joined the Allies in 1917 and helped end the conflict a year later. These Americans had their first real brush with war when they boarded that steamship. For 13 days, 108 male athletes (the U.S. only sent15 women, none in track and field) bunked in the hold beneath the waterline among the rats and the stale stench of death. “Dad said it smelled terribly of formaldehyde,” Robert Massengale says. “Training [onboard] was difficult.”

The haunting passage was nothing compared to the actual ruin that awaited them in Europe. Belgium had been ground zero for the Great War’s notorious Western Front, the first stop on Germany’s march to France. Antwerp and its population had been decimated. The city had little more than a year to prepare its war-torn streets and buildings for the event — a task that generally took countries four to five years in peacetime. The city hurriedly threw up facilities, including the 30,000-seat Olympisch Stadion, and quartered visiting athletes wherever space could be found. European youths who had lived through six years of war and its aftermath expected and even appreciated the rustic accommodations. But the Americans, who’d grown up on the other side of the globe, found the old schoolhouse they were boarded in — with its straw-stuffed mattresses; cold-water showers; meals without milk, butter, or sugar; and smell of the antiquated subterranean sewers — unacceptable, so much so that they circulated a petition calling for improvements.

Dubbed “The Mutiny of the Matoika” by the press, at best the petition made the young Americans seem obtuse to a continent ravaged by war. At worst, it made them seem insensitive. These were mere boys, some still teenagers, in a world far less interconnected than today. Many of these young men had never before experienced the world outside of their home countries, regions or even states in which they were born — and that included the contingent from Mizzou.

A Tiger dream team

Around 1920, according to Olympic historian Bill Mallon, America was entering a golden age of sprinting. This was in large part because it was one of the first to retain expert coaches who instituted regimented training for their amateur runners. The best coaches attracted the best talent, so, it was common enough for a university or athletic club to send more than one athlete to an international meet or an Olympics. After the 1919 track season, Mizzou hired Robert Simpson, a former Tiger runner and future MU Intercollegiate Athletics Hall of Famer who was, himself, a world-record-holding hurdler and two-time gold medalist in the Inter-Allied Games in Paris, as its new track and field head coach. His first crop of Olympic qualifiers didn’t disappoint.

The headliner was Jackson Scholz. The Buchanan, Michigan, native was already 23 years old, had lettered three years at Mizzou and was a budding star on the international scene. Next came Brutus Hamilton, a soft-spoken intellectual from Peculiar, Missouri. Despite suffering a severe hip dislocation as a boy, Hamilton went on to win state titles in the high jump, pole vault, broad jump and shot put. He was considered one of the U.S. team’s finest all-around athletes. And then there was Massengale, a track star hailing from Webster Groves High School. His father agreed to pay for the lad’s college education in exchange for the promise that he’d return and work for the family steamboat business.

In Antwerp, Scholz was up first in the 100-meter. But after winning his first heat and quarterfinal with the fastest time at these Olympics (10.8 seconds, two-tenths of a second away from the world record), he faded late in the final, finishing a disappointing fourth. That same day, Hamilton competed in the pentathlon, leading the event after winning the long jump portion but then struggling through the other four events en route to a sixth-place finish. Hamilton later redeemed himself in the decathlon, never winning a single event but doing well enough in all of them to take the silver — the first Olympic medal in Mizzou history.

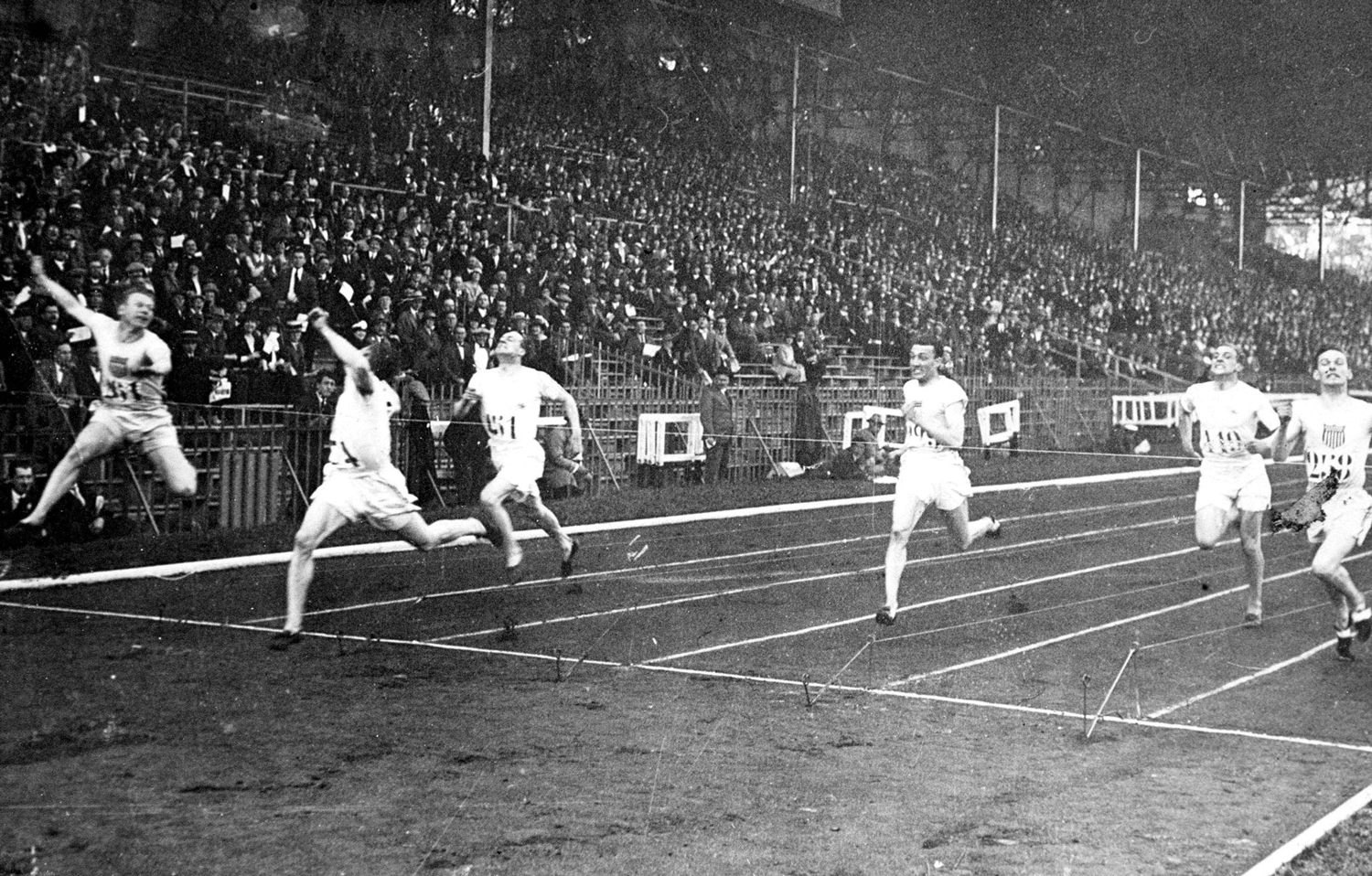

Next came the 200-meter. Massengale stood by and watched the final field of six, including U.S. alternate Woodring, take their marks.

“Pret,” called the official — “Ready” — an order that echoed through the stadium, reverberating off of hundreds of seats left vacant by locals who still couldn’t afford the three francs for admission or didn’t want to brave the cold rain.

Pop. The starter’s pistol registered, sending the six sprinters dashing. American Charley Paddock, who had won the 100-meter gold, bolted out to a quick lead, causing Brit favorite Harry Edward to accelerate his deliberate pace. Both were gassed when, about 20 meters away from the finish, Woodring — like Massengale, long and lanky — came out of nowhere to beat them to the tape. The alternate from Syracuse University had taken the gold.

The final event involving a Tiger was the 4-x-100 meter relay. Led by Scholz, the Americans prevailed, winning Mizzou’s second medal of the games and its first gold. The celebration was bittersweet for Massengale — he was supposed to have been on the relay team, too.

Regalia and regret

Of course, Mizzou has gone on to send many more Olympians to compete — but they were never more successful than in Antwerp, a century ago.

The only other time MU would ever bring home two medals from the same games was in Paris 1924, when Scholz did it himself, winning both gold and silver in the 200-meter and 100-meter, respectively. He also won a national championship in 1925 and returned to the Olympics a third time in 1928, though he finished fourth in the 200-meter in Amsterdam. He became a prolific writer of pulp fiction sports books and was inducted into the U.S. Track and Field Hall of Fame in 1977. “Scholz was definitely an anomaly for his time,” says Glen McMicken, statistician and historian at U.S. Track and Field. “It was rare for athletes to stick around in the sport to compete in two Olympic Games, and he was in three. He was the first man to make a sprint final in three Olympics.”

Ironically, Scholz is now probably better known for a loss — his silver-medal performance in the 100-meter back in 1924 in Paris. He lost to Brit Harold Abrahams, the subject of the 1981 Oscar-winning film Chariots of Fire. That race and Scholz are portrayed in the movie, though he said he never saw it, and he died five years later.

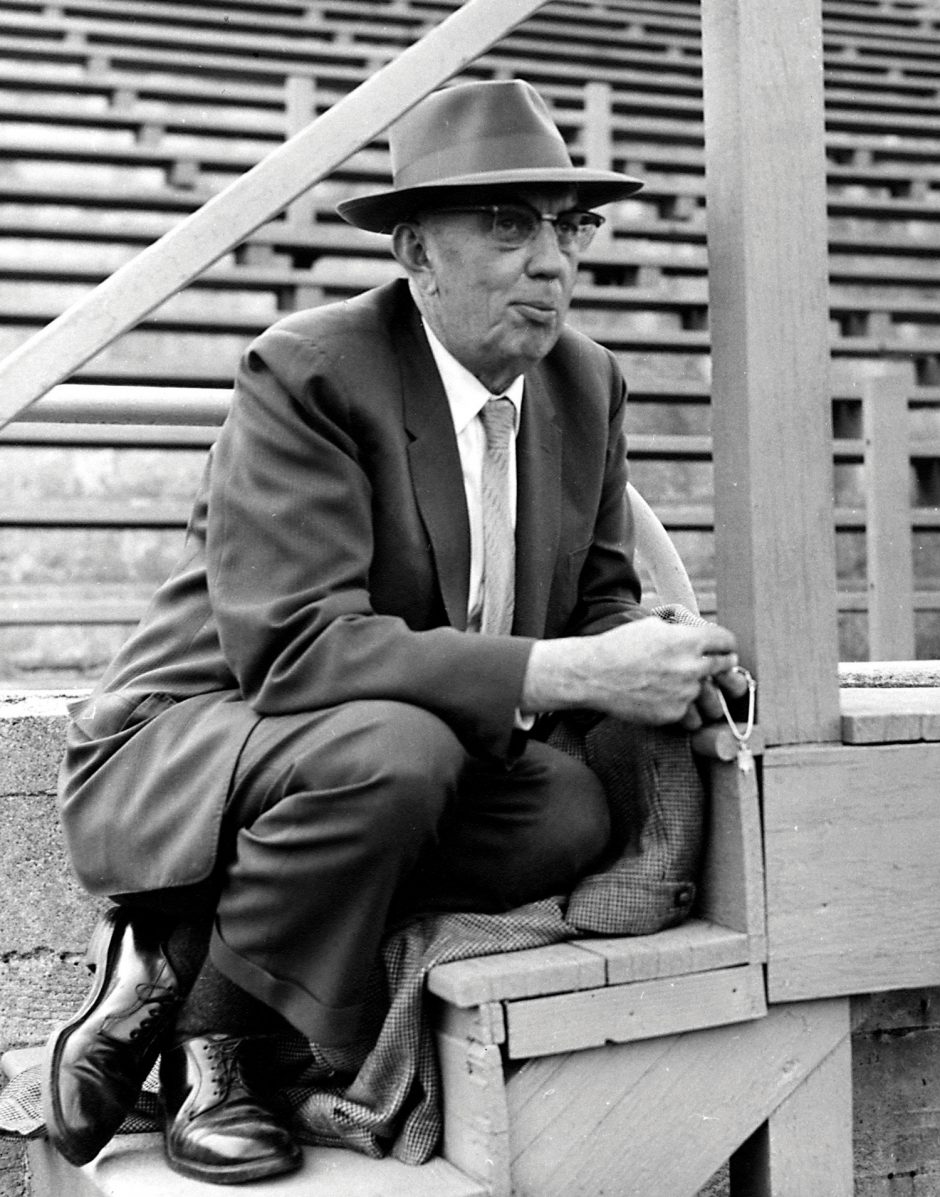

Hamilton returned for the 1924 games as well, finishing seventh in the pentathlon. After his competitive career, he landed the job as U.S. decathlon coach for the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles. Hamilton then stayed in California, where he coached track and field at the University of California, Berkeley, and eventually worked as athletic director until his retirement in 1965. He also coached the entire U.S. track and field team in the 1952 Olympics, the 1953 Maccabiah Games in Israel and the 1965 meet against the USSR. During that time, “Brutus,” as his “boys” called him, helped develop some of the world’s great track stars, including Archie Williams, Dave Maggard, Jack Yerman and Don Bowden, the first American to break the 4-minute mile. “He never talked about his Olympic accomplishments [as an athlete] at all,” Bowden says. “I never realized it until people told me — we had to research it ourselves. We respected him so much as a person that his accomplishments did not have a bearing on our relationships.”

Massengale never ran competitively again. His ailment caused him so much pain that, upon graduation in 1922, his father sent him to a rest home in Colorado Springs in hopes the professionals and the cool, dry Colorado air could help. Massengale eventually returned to fulfill his promise of working at the family business and later took an office job with Union Electric. He settled down and raised three sons, two of whom followed their father to run track at Mizzou. One of them, Robert Massengale, says his father rarely spoke about his brush with Olympic greatness.

“He didn’t talk about it a lot, and I didn’t have the sense to ask him,” Robert says. “Dad was an easygoing guy, low-key. But I know he had regrets.”

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.