June 29, 2020

Contact: Austin Fitzgerald, 573-882-6217, fitzgeraldac@missouri.edu

In nearly two decades of working as a researcher at the University of Missouri, Chung-Ho Lin has never felt the urge to study human waste. But science isn’t always glamorous work, and now, to help put a stop to the COVID-19 pandemic, Lin and his team in the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources’ MU Center for Agroforestry are willing to do whatever it takes.

Recent studies from around the world have shown that the virus responsible for COVID-19 can be detected in waste, a discovery that has paved the way for a new kind of early warning system for communities at high risk of an outbreak: wastewater monitoring. As part of a project funded by the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services and the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, MU researchers will be monitoring wastewater in areas throughout Missouri for one year to detect any presence of the novel coronavirus.

It might sound simple; Wastewater is collected from sewer systems and sent to MU researchers for analysis. But that analysis is a complex, multistep process requiring intensive preparation.

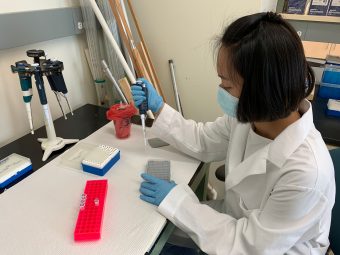

First, wastewater samples are sent to Marc Johnson, a professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at MU’s Christopher S. Bond Life Sciences Center. Johnson’s lab extracts viral genetic material from the sample in the form of RNA, which is then sent to Lin’s team for examination. Using a process known as quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR), which amplifies the samples for more detailed study, Lin’s team is able to determine whether the virus is present, and quantify the concentrations. The technique has been central to Lin’s work for 15 years, but this is the first time he has applied it to study a human virus.

“Our team has been working around the clock,” said Lin, who earned a PhD from MU in 2002. “With help from Dr. Johnson, we were able to develop our method within three days, and we spent more than two weeks optimizing that method for the particulars of this virus. There were a lot of parameters that needed to be fine-tuned to increase the sensitivity of our method, and that meant long days in the lab.”

With the assistance of Hsin-Yeh Hsieh — a research scientist at the College of Veterinary Medicine and the Christopher S. Bond Life Sciences Center — and two students, Lin said he has developed a method of RT-qPCR that works more accurately with the SARS-COV-2 virus than standard methods, one that could make wastewater analysis quicker, cheaper and more effective. Hsieh is a frequent collaborator of Lin’s, and the team noted her expertise in molecular biology was invaluable in designing and optimizing their method.

The researchers plan to eventually test 80 sites per week, meaning communities from all over the state could have advance warning if the virus is obtaining a foothold in their area. The speed of this project, from execution to real-world impact, has made an impression on the two students on Lin’s team.

“It feels incredibly satisfying to have an opportunity to work with this team on a project that could contribute to mitigating current health issues,” said Sydney Oberdiek, a senior pursuing a bachelor’s of science degree in biochemistry.

Shu Yu Hsu, a second-year PhD student in the MU Center for Agroforestry bioremediation program in the School of Natural Resources, agrees.

“I think this is a great opportunity to apply science to solving a problem in the real world,” Hsu said. “We are learning a lot from each other on this project. Everyone on our team is supportive.”

Lin said the project, known as the Coronavirus Sewershed Surveillance Project, is a rare opportunity to have an immediate impact in a field that often requires years of work before the tangible benefits of research begin to become apparent.

“It is gratifying to be able to be able to respond scientifically to a serious current issue like COVID-19 and have results that communities can act on immediately,” Lin said. “Science has the reputation of having a gradual pace, but I think we are seeing the ability of researchers to respond and innovate quickly, whether they are developing vaccines or monitoring wastewater. To be a part of the worldwide response to this public health threat, and to see my colleagues at the University of Missouri addressing so many different aspects of that threat, is inspiring.”