Jan. 10, 2020

Contact: Eric Stann, 573-882-3346, StannE@missouri.edu

A 550 million-year-old fossilized digestive tract found in the Nevada desert could be a key find in understanding the early history of animals on Earth.

Over a half-billion years ago, life on Earth was comprised of simple ocean organisms unlike anything living in today’s oceans. Then, beginning about 540 million years ago, animal structures changed dramatically.

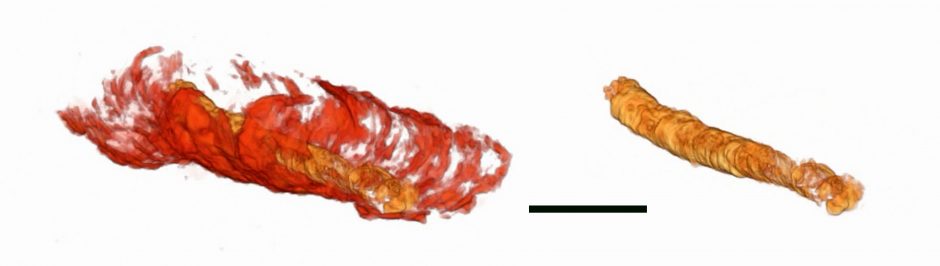

During this time, ancestors of many animal groups we know today appeared, such as primitive crustaceans and worms, yet for years scientists did not know how these two seemingly unrelated communities of animals were connected, until now. An analysis of tubular fossils by scientists led by Jim Schiffbauer at the University of Missouri provides evidence of a 550 million-year-old digestive tract — one of the oldest known examples of fossilized internal anatomical structures — and reveals what scientists believe is a possible answer to the question of how these animals are connected.

The study was published in Nature Communications, a journal of Nature.

“Not only are these structures the oldest guts yet discovered, but they also help to resolve the long-debated evolutionary positioning of this important fossil group,” said Schiffbauer, an associate professor of geological sciences in the MU College of Arts and Science and director of the X-ray Microanalysis Core facility. “These fossils fit within a very recognizable group of organisms — the cloudinids — that scientists use to identify the last 10 to 15 million years of the Ediacaran Period, or the period of time just before the Cambrian Explosion. We can now say that their anatomical structure appears much more worm-like than coral-like.”

The Cambrian Explosion is widely considered by scientists to be the point in history of life on Earth when the ancestors of many animal groups we know today emerged.

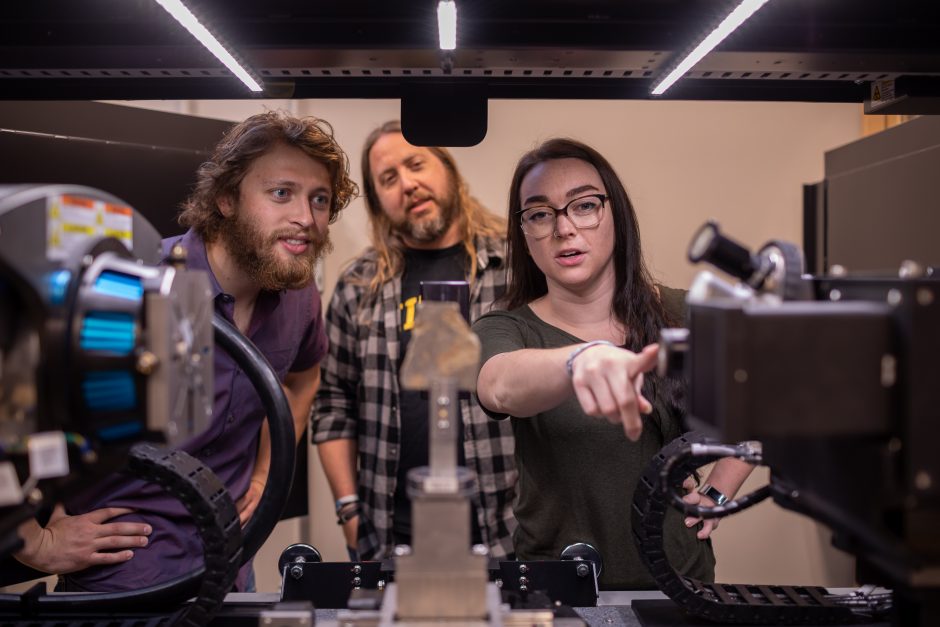

In the study, the scientists used MU’s X-ray Microanalysis Core facility to take a unique analytical approach for geological science — micro-CT imaging — that created a digital 3D image of the fossil. This technique allowed the scientists to view what was inside the fossil structure.

“With CT imaging, we can quickly assess key internal features and then analyze the entire fossil without potentially damaging it,” said co-author Tara Selly, a research assistant professor in the Department of Geological Sciences and assistant director of the X-ray Microanalysis Core facility.

The study, “Discovery of bilaterian-type through-guts in cloudinomorphs from the terminal Ediacaran Period,” was published in Nature Communications. Other authors include Sarah Jacquet from MU; Rachel Merz from Swarthmore College; Michael Strange from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas; Yaoping Cai from Northwest University in Xi’an, China; and Lyle Nelson and Emmy Smith from Johns Hopkins University.

Funding was provided by grants from the NSF Sedimentary Geology and Paleobiology Program (CAREER 1652351) and Instrumentation and Facilities Program (1636643). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.