July 16, 2019

Contact: Austin Fitzgerald, 573-882-6217, fitzgeraldac@missouri.edu

July 20 will mark the 50th anniversary of humanity’s first steps on the moon, a feat of technological wizardry and audacity once unparalleled in history. Then and now, it nearly defies imagination: Three men guided machinery with less computer power than an iPhone all the way to the moon, and there was no guarantee of success — President Nixon even had a draft of a speech prepared in the event that none of them returned. But the legacy of America’s sprint to the moon is more than the awe it inspired. Its impacts can still be felt today at universities across the country, including the University of Missouri.

Mizzou’s involvement with the space program stretches back to 1964, when its own Space Sciences Research Center was established. While Mizzou was the epicenter of this project, housed in a $1.5 million facility ($12 million adjusted for inflation) that supported dozens of space-related research projects, the center also had a significant presence at Missouri University of Science and Technology in Rolla and the University of Missouri-Kansas City. Kickstarted by more than $2 million in allocations from the Missouri Legislature, the plan was to create an enormous, system-wide research engine that would lead the nation in university-driven space science research.

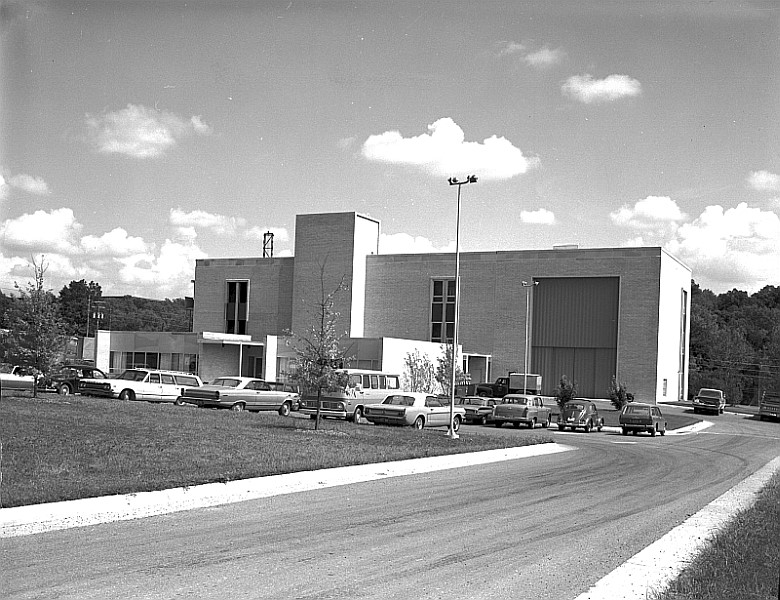

The Space Sciences Research Center’s flagship facility, located near the MU Research Reactor, as it appeared soon after construction.

At Mizzou, much of the focus was on hibernation — the ability of certain species to survive in unfavorable conditions by slowing their metabolic rate via a process known as depressed metabolism. If humans were going to survive in the hostile environment of space, they would need to learn from animals that survived improbable conditions on Earth. Unsurprisingly, NASA had made this area of research a priority.

The center attracted some of the nation’s top scientists, including Rowand Chaffee, a zoologist who came to Mizzou from the Los Alamos National Laboratory. By the spring of 1965, only a year after its creation and still more than a year away from the completion of the first stage of its permanent facility, the Space Sciences Research Center was involved in 20 separate research projects on Mizzou’s campus, at least two of which were funded by NASA. By the following year, there were more than 40 projects systemwide.

The center was also part of a nationwide trend: An overwhelming number of universities (and municipalities) around the country attempted to develop their own “space centers” in the 1960s after President John F. Kennedy pledged to put a man on the moon by the end of the decade. But amidst this national craze, Mizzou stood out for the large number of projects and researchers it dedicated to space-related life sciences. Faculty from the colleges of Agriculture, Arts and Science, Engineering, Veterinary Medicine and the School of Medicine worked on such projects as “energy metabolism in artificial atmospheres” and “photosynthetic and gaseous exchange rhythms in dormant plants.”

There could be no doubt Mizzou was aiming high. “It is our belief,” the center stated in 1966, “that the ultimate object of the space effort is Man’s colonization of, and full adaptation to, extraterrestrial environments.”But with the moon landing in 1969 came a change of priorities, and not long after, the Space Sciences Research Center and its flagship Mizzou facility became what is now the Dalton Cardiovascular Research Center.

An era had ended, though the transition was smooth. To this day, Dalton works with researchers in many of the same colleges and departments as it did in its space research days. Nor did space-related research vanish from campus. Indeed, space remains a vibrant part of Mizzou’s body of research, and people all around campus have connections to, and unique perspectives on, the space program.

A spacewalk snafu

When it comes to Linda Godwin, it’s putting it mildly to say she has a “connection” to the space program. As a former astronaut with more than 38 days spent in space over the course of her career, the anniversary of the moon landing hits close to home.

“I don’t know that my interest in science would have been the same without the Apollo Program,” said Godwin, who was in high school when Neil Armstrong set foot on the distant rock. “Like so many young people at the time, I was awed and inspired by what I saw on TV.”

Linda Godwin logged more than ten hours of extravehicular activity in outer space during her career as an astronaut.

Godwin received a master’s and doctorate in physics from Mizzou, and after a successful career at NASA — in which she became an astronaut just five years after joining the agency — she returned to her alma mater as a professor of physics and astronomy. Though her research interests now lie in the less human-centered realm of astronomy, she still recalls the impact of seeing the Earth from outside the atmosphere.

"It only took 90 minutes to orbit the planet, and to go from one side to the other so quickly really made everything seem interconnected. It certainly gave me a renewed understanding of the importance of preserving our planet,” she continued.

Godwin never made it to the moon herself, but she did perform two spacewalks, and so when NASA announced its first all-female spacewalk, she was listening. When the spacewalk was scrapped in March because of a lack of medium-sized upper torso components (HUTs) on the available spacesuits, she knew what had happened.

“There are only medium and large-sized HUTs, which could put women at a disadvantage, because they tend to have smaller shoulders. They are expensive to produce, so there isn’t a lot of leeway when it comes to sizing. Unfortunately, wearing a suit that is too big can impair movement and precision, so I really respect the astronaut’s decision not to wear a larger suit even though the walk had already been announced.”

For Virginia Huxley, JO Davis Professor of Cardiovascular Physiology and director of the National Center for Gender Physiology at Mizzou, the spacewalk snafu was a perfect example of the importance of considering both men and women at every stage of space research and development.

Huxley once worked on NASA-funded research at Mizzou that sought to explain why smaller people — many of them women — tend to faint upon returning to normal gravity from space. The study was halted when she realized that there hadn’t been enough prior research on female physiology to pursue the study.

“Researchers were investigating all sorts of different effects of space on humans, but they were only using men in their studies,” Huxley said. “We have seen again and again that sex differences in humans and other animals are not inconsequential, and yet a large portion of space-age research was only advancing our knowledge of one half of the human race. This made it more difficult for women to become astronauts, because it allowed for certain excuses, such as the idea that the menstrual cycle would endanger women in space.”

At the urging of Huxley and others, many researchers now include both sexes in their studies. Still, Huxley said there is work to be done.

“It’s getting better, but we’re not there yet. Unfortunately, I was not surprised when NASA canceled the spacewalk. It’s not specifically a NASA issue; it’s in many areas of research. Time and time again, we have encountered situations where women have to play catch-up because there is some nuance that wasn’t considered.”

Engineering the future

While the Space Sciences Research Center is long gone, space-related research continues across Mizzou. In the College of Engineering, Craig Kluever, a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering, worked in space shuttle guidance, navigation and control for an aerospace manufacturing company before joining Mizzou. His aerospace research has been funded by NASA. Haojing Yan, an associate professor of physics and astronomy, studies galaxy formation and evolution over cosmic time. Electrical engineering and computer science professor Jae Kwon’s work includes batteries and nanotechnology that can be applied to satellites. The list goes on.

For students, there is the Mizzou branch of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, as well as Mizzou’s Students for the Exploration and Development of Space.

In addition, there is a long list of alumni like Brooke Harper, a graduate of the College of Engineering and NASA engineer who recently made national headlines for her unique celebration of a successful Mars rover landing. Micheala Sosby and Haley Reed, two recent alumni from the School of Journalism, helped create NASA’s new audio series, Nasa Explorers: Apollo.

The origins of life

Of course, space-related research isn’t always as straightforward as building rockets. Just as researchers at Mizzou’s Space Sciences Center once studied hibernating animals to gain insight into human metabolism, Donald Burke-Agüero is experimenting with RNA (ribonucleic acid, which regulates the expression of genes and acts as a messenger of genetic information from DNA) to help NASA understand the origins of life.

Donald Burke-Agüero is studying RNA in order to unlock the mysteries of the origins of life and the universe.

“There is a hypothesis that life began as RNA,” said Burke-Agüero, a professor of molecular microbiology and immunology and a joint professor of biochemistry at Mizzou’s Christopher S. Bond Life Sciences Center. “If this is true, then the more we learn about the biological and chemical functions of RNA, the more we know about how life began.”

This may seem surprisingly abstract for the likes of NASA, but understanding the origins of life has an important practical purpose.

“One of the things NASA needs to do is identify possible signs of life in its early stages on other planets, and you can only recognize what you know. If we only knew of oxygen-based life on Earth, for example, we would only look for life in the presence of oxygen. But we recently discovered marine life that appears to be able to live completely without oxygen. As we learn more about every possible permutation of life, NASA has a better idea of what to look for on other planets.”

With the help of doctoral student Haritha Dhanikonda (and Jordyn Lucas, before she graduated recently), Burke-Agüero uses molecular evolution techniques to develop artificial ribozymes, which are RNA molecules that catalyze chemical reactions. Through the process of creating new applications for RNA, Agüero hopes to contribute to a better understanding of how RNA may have developed into more complex forms of life.

Unlike Burke-Agüero, who was in Kindergarten when the moon landing occurred, Lucas and Dhanikonda can only imagine what it was like to witness such a momentous event. Still, its significance is not lost on them.

“I grew up in Chennei, India, and people there didn’t have the means to connect to the rest of the world through technology like they do today,” Dhanikonda said. “Even so, they knew Neil Armstrong’s name. The moon landing had a worldwide impact — as Armstrong said, this was a giant leap for mankind, not just for America. All over the world, people understood that this was an incredible accomplishment.”

Researchers like Burke-Agüero are thriving at Mizzou as they work on research that contributes, directly and indirectly, to scientific knowledge of our solar system and the cosmos. It has been half a century since the space sciences research center closed permanently, but Mizzou is still carrying on its work. As we acknowledge the 50th anniversary, our researchers are looking to the skies, eager to discover where their work will take them next.

![062625_CEI Aerial View_email-cropped[29] (1)](https://showme.missouri.edu/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/062625_CEI-Aerial-View_email-cropped29-1-940x529.jpg)