I remember the moment that I promised myself I would never father a child. The moment happened 55 years ago. Yet I can still turn my eyes from whatever I am looking at and call it up with lapidary precision. That night. The glitter. That station wagon.

The setting is Gaslight Square in St. Louis. The square was in the middle of its dozen-year existence — a vapor-lit Milky Way of Dixieland joints, piano bars, and jazz and blues venues that spilled eastward down Olive Street from Boyle until it trickled into darkness.

The nighttime sidewalks on both sides of Olive were thronged with girls in bee-hive bouffants and guys in Vietnam-ready crew cuts: the hip, the groovy, the young, the Forever Young.

I was feeling kind of hip and groovy myself on that spring night in 1964. A year out of Mizzou, I had landed a cool gig: sportswriter for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. And here I was on the square with a bunch of college buddies. We were standing out in front of a hot pastrami mecca called Jack Carl’s 2 Cents Plain. I was inspecting a young dolly-bird in a short mod dress and go-go boots when, for some reason, I shifted my gaze to the street and spotted the station wagon.

It was crawling eastward in the honking traffic. A Ford Country Squire, I think. Brown and yellow. A real Atomic Age job. The gaslights illuminated the faces inside. Dad was behind the wheel. Mom was beside him. In the back seat were Sis and Junior. I’m pretty sure there was a dog, and I’m pretty sure the dog’s name was Spot.

In an instant the gas-lit lamps of Gaslight Square glowed a hellish red as the future slouched in behind that station wagon. A rage boiled up inside me. I must have registered it somehow; my friends shot me glances. I said nothing to them — how would I have explained it? — and we made our way inside Carl’s.

But I knew exactly where the rage came from. It came from my sense of an invasion. One that threatened my identity.

My world of the Forever Young had been breached — violated — by this family and its goddamn station wagon. They represented everything I loathed and feared about what my future might bring. A parade of invective — contempt — streaked through my mind like life flashing before death: These people were plastic! They were ticky-tacky! Uptight! Straight arrows! Honkies!

I made a promise to myself as I watched this un-welcome wagon creep off into the dark adult reaches beyond the square. No children, ever, for me.

* * *

Flash ahead 12 years. Twelve years of the single life. Of “Is that all there is?”

In May 1976 I took a leave of absence from the Chicago Sun-Times, where I was laboring as a TV critic, and rented a country house on the southern tip of Lake Michigan. I planned to write a book. And score with as many chicks as I could lure to the Michigan Dunes.

On a return flight to Chicago from New York after a round of interviews, I took my assigned aisle seat. And looked up to see Honoree Mary Fleming walking … down the aisle. Green eyes, auburn hair that flowed to her waist. And wonderfully, no mod dress, no go-go boots. She was, is, the picture of Celtic beauty. I whispered, “Please, God, for the few good things I’ve done in my life, let her sit next to me.”

God let her sit next to me. The station wagon receded.

She later told me that she’d hid the physics textbook she’d been reading — she was a recent PhD in biophysics at the University of Chicago — so I wouldn’t think she was a nerd.

We were married on Oct. 8, 1978, at the Ethical Culture Society in New York. After the ceremony, we took a taxi to the West Side apartment we’d been sharing, where Honoree, still in her wedding dress, baked the hors d’oeuvres for our guests.

We were ardently in love, and still are. Yet in 1978, children remained an abstraction to me. Children were fine. But children happened to other people. I would stay Forever Young.

* * *

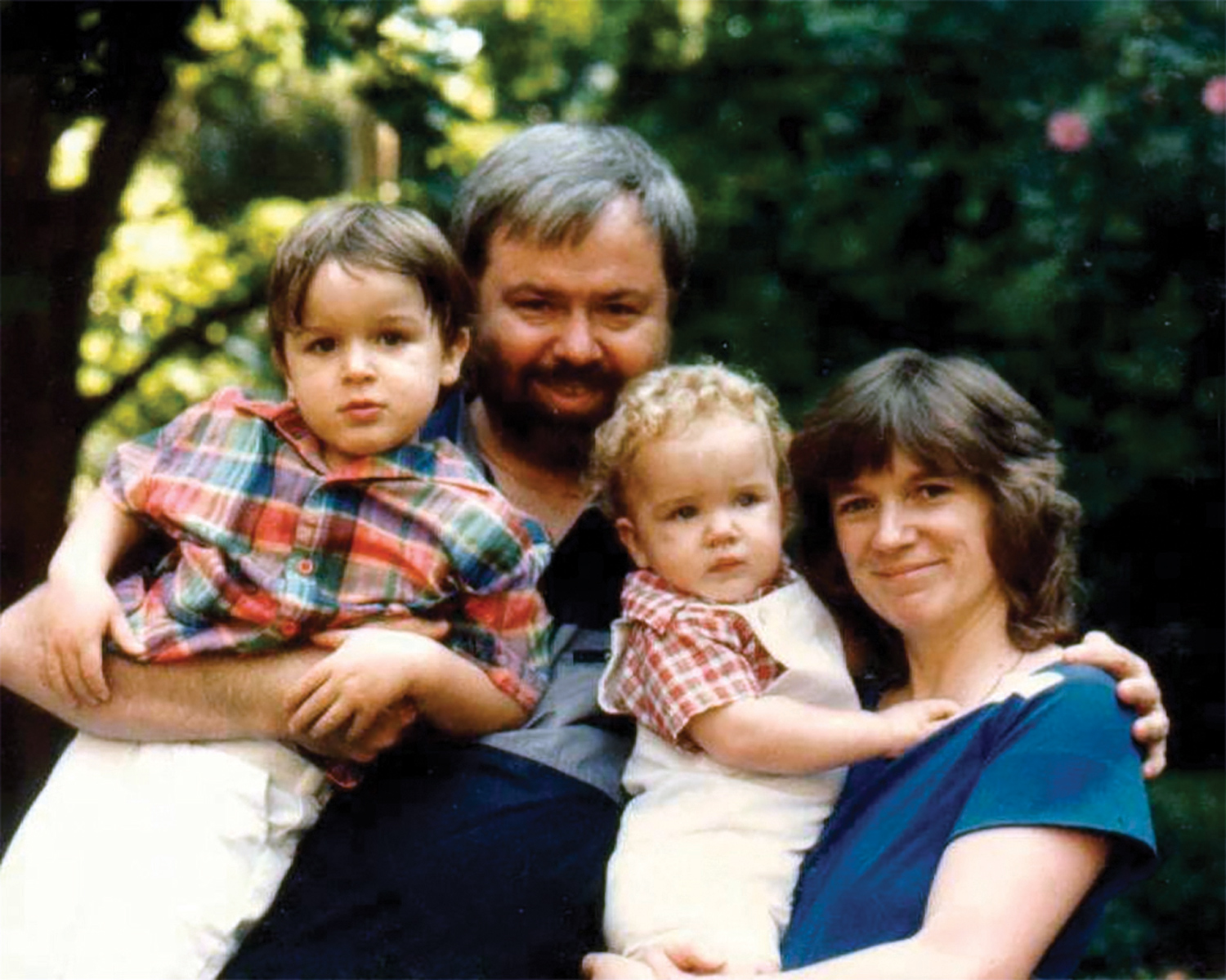

Dean Paul Justin Powers was born on Nov. 18, 1981. My 40th birthday. The station wagon receded further, and my world re-formed itself around the aura of this luminous, dreamy child. As he grew, his blue baby-eyes transmuted themselves into hazel — my brown, dancing with Honoree’s green; his thick caramel hair spilled over his forehead, and his cheeks glowed crimson. I thought of him as a child the color of wheat and apples. With his small hand gripping mine on our daily short walk from our apartment to Riverside Park — where Dean would inevitably cause kid-gridlock as he stood motionless at the top rung of the slide, gazing into New Jersey — I felt my Midwestern anxieties about the city slip away. No bad guy could harm me; no light-running crosstown bus flatten me. Dean Powers was at my side.

Kevin Berkeley Powers rocketed into the world on July 21, 1984, nearly streaking through the outstretched hands of the obstetrician. In a sense, he never slowed down. We’d moved into a house north of the city by then. Kevin loved velocity: high arcs on the backyard swing, tearing around the downhill curve full tilt on his mobile bulldozer, his yellow curls flowing behind him; years later, skiing at breakneck speed down Vermont slopes with his graceful brother. One summer day in his first year, as he sat watching his mom from his highchair in the kitchen, Honoree hummed some musical scales. Kevin startled her by shrieking with laughter. Honoree hummed the scales again; another shriek of delight. Again. Another shriek.

Musical genius was roiling in Kevin, probing for a way out.

* * *

Schizophrenia is rare. It strikes between 1.5 and 4 percent of the world population. Yet it is far from benign, nor just another form of “mental illness.” It is not a product of depression or alienation or alcoholism or any other complaint of the “worried well,” to use Freud’s term.

It is a disease not of the metaphorical “mind” but of the physical brain. Its victims are usually adolescents in the final dangerous phase of the brain’s cell reformation and carriers of a rare cluster of inherited, flawed genes stimulated to destructive action by an overflow of normally protective chemicals such as serotonin or dopamine. This overflow can be triggered by “environmental” upheavals such as severe stress. The resulting brain destruction can be largely stabilized by accurately prescribed medication. It cannot be cured.

Some neuroscientists, including Nancy Coover Andreasen of the University of Iowa, have established that a high correlation exists between creativity and madness. Writers show significant incidences of schizophrenia.

And musicians.

* * *

Honoree and I never saw any of it coming. In those lamb-white days (as Dylan Thomas phrased it), we remained as clueless and heedless as anyone about this disease. Schizophrenia happened to other people.

Our family embarked upon a hegira of happiness that lasted for 20 years. We departed New York for Middlebury, Vermont, where I taught each summer at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference. Honoree and I received appointments at Middlebury College — she in the biology department; I in creative writing.

Dean and Kevin floated in arcadia. The seasons enveloped our small town in their New England rhythms: football and foliage in the fall, neighborhood caroling at Christmas, the big community bonfire and ice-skating and hot chocolate on New Year’s Eve, the Festival on the Green in summer. Swim team (Dean’s relay team set a state record, with rangy Dean swimming backstroke). Community theater. And the Bread Loaf conference in August, held on its manicured 19th-century mountain-meadow campus. Our family was assigned Robert Frost’s clapboard summer cabin, where my sons fell asleep to the organ-stop of howling coyotes from the nearby forest.

Kevin talked his way into guitar lessons at age 5; within a year, his college-guy instructor confessed that he had nothing more to teach our son. We persuaded a seasoned but skeptical town musician (“Six years old?!”) to take him on. The instruction melted into exercises of call-and-response sessions, which melted into thrilling duets, which melted into wondrous improvisational guitar concerts, sadly confined within Michael Corn’s little studio down an alley from the town bagel bakery. These concerts had an audience of one: me, sprawled and enraptured on the linty carpet.

At 14, Kevin won DownBeat magazine’s Student Music award in two categories, jazz and rock.

Dean, after years of looking on with interest, now requested his own instruction. He would never match Kevin’s musicianship — few would — but he unveiled a genius for lyrical songwriting. The image of the two of them jamming at some festival or open mic around the state — heads bent over their instruments, knees touching, shoes crossed, nodding subtle signals to each other, grinning sheepishly at the applause — this image has become part of my DNA.

This was hardly the sterile life I had read into those blameless people inside that long-ago station wagon crawling along Gaslight Square. And speaking of DNA, had something in my own brain, perhaps itself a host to that rare yet un-activated cocktail of flawed genes, been trying to warn me not to go there?

* * *

We sent our sunny younger son off to the Interlochen Arts Academy in 1999. In that same year, Dean enrolled for a postgraduate prep year at the Gould Academy in Maine, before embarking on his collegiate years at Colorado State University.

I drove Kevin across Canada and south to the beautiful Michigan campus. He arrived full of anxiety about how to talk to girls. He graduated three years later under this benediction from his guitar teacher: “Kevin is the most talented musician I have encountered in my years at Interlochen.”

From our Vermont vantage point 900 miles away, it was impossible for Honoree and me to analyze our son’s growing mood swings, expressed in emails and telephone calls. Had we witnessed them in person, we probably would have interpreted them as the normal turmoil of an adolescent. We would have been wrong.

It was at the Berklee College of Music in Boston, in the fall, that Kevin came apart.

A phone call to our Middlebury home one predawn morning: “Mom, Dad, I’m going to Russia! My guitar instructor invited me on a tour with a combo!” We innocently gushed congratulations, not picking up on the strain in his voice until we noticed that he was no longer on the line.

We tracked him down at a hospital in Syracuse. He’d boarded a Greyhound in Boston after the call, intending to cross the country to Los Angeles and get a job as a rock star. Unthinkably for our gentle, happy-go-lucky son, he’d been thrown off the bus after accosting the driver and taken to the hospital by state police. We brought him home, sedated.

The three years that followed remain emotionally difficult for me to recount in detail. Here goes an attempt at the essential moments:

At the hospital, we asked one another: Was it a bad reaction to a drug trip?

Nothing that hopeful. We soon learned that Kevin had been stricken with bipolar disorder.

A summer of recuperation at our house, then back to Berklee.

A call from him one autumn night as we prepared a pasta dinner: “Come and get me!” We abandoned dinner, jumped into our car and sped the 200 miles to Boston.

We found Kevin shivering and gaunt on a street corner near his apartment. He slept in the back seat all the way home.

And then a new and more horrifying psychiatric diagnosis: schizophrenia.

A rehabilitative summer in Colorado Springs in Dean’s care, a summer of sublime music-making and recording. And a medication regimen.

Then a cataclysmic mistake: Kevin begged to stay on in Boulder by himself when Dean came home for Thanksgiving. Honoree telephoned him a recipe for roasting a turkey, a fact that still breaks my heart. Dean returned to their apartment after three days and found his brother slumped and gazing at what he said was a large blue musical note suspended in midair. He had stopped taking his medication. His untreated psychosis had almost certainly deepened.

* * *

Back to Middlebury. Kevin lived with us, still sleeping with his socks on as he had from childhood, and in the company of his cat, a feline pillow of a Maine coon named Spikey. He took classes at nearby Castleton State College, where Honoree was now dean of education. He played the best jazz guitar of his life — the last year of his life — in a combo led by the college’s music instructor, at Vermont bars and jazz clubs.

But by then, a great amount of Kevin’s personality had deserted him. Normally an impish chatterbox, he now was mute at home, staring at something the rest of us could not see. The sounds from him were mainly giggles: He was listening to the voices in his head.

Honoree and I were ravaged by the realization of our own powerlessness. There was nothing we could do, except shepherd our beautiful son, and … shepherd our beautiful son.

* * *

Then came July 15, 2005, a week before his 21st birthday. Kevin had informed us a few weeks earlier that he had gone off his meds again and would not resume them: He was fine. We pleaded. He remained adamant. This resistance is tragically common to schizophrenia sufferers. It has a name: anosognosia, Greek for “lack of insight.”

Honoree and I knew well that stabilizing medications were the only hope for people in Kevin’s condition. We understood the consequences of anosognosia. But we could not make Kevin understand. He was fine.

We were not fine. We lived in helpless dread.

Friday, July 15, was a recycling day. On my second early-morning trip through the basement with a vinyl bag in either hand, I grew aware of a presence behind my right shoulder. I turned and saw Kevin. His head was bowed. His yellow hair was illuminated by light from a dirty window. This was his trademark guitar-playing posture. But Kevin was not playing the guitar.

Forever Young.

* * *

It seems unfair to Dean to conclude my family story with but a brief summation of his own ordeals with schizophrenia. Yet Dean himself, a private soul like his mother, prefers it this way.

Dean was stricken a few years after Kevin’s suicide. The loss of his brother had been just one of several contributing stresses he had suffered. The dark years commenced again in our family, years that included Dean’s own suicide attempts.

This time, we were all spared the worst.

The psychiatrist who rescued Dean understood the menace of anosognosia. He devised a strategy to help our son surmount it: Instead of oral medications, he assigned Dean to a monthly injection of a drug called Haldol. This made Dean directly accountable to a clinician. The doctor warned our son that if he missed appointments, he would end up in a hospital bed for an indefinite period. Dean loathes hospitals even more than he loathes needles. His treatment has worked for five years, and his re-entry into the light is a blessing in our lives.

* * *

The three of us now form a small, loving universe in a house on a hillside above Castleton, Vermont. We gather each evening on our front deck or, if it’s cold, in our living room, to celebrate a period of quiet conversation organized by Dean, who calls it “Happy Hour.” It is a happy hour indeed.

Honoree has finished writing up the results of her 40-year investigation into cell growth and movement, with its implications for understanding cancer. They are pending publication. I give talks and write blog entries that advocate for drastic reform of our country’s shockingly dilapidated mental health-care systems. Dean writes and spends time with his beloved companion, the amiable pit bull/boxer known as Rooster the Wonder Dog.

And somewhere, I like to imagine — somewhere as far away as a guitar chord played years ago and now spiraling through the heavens — a brown and yellow Ford Country Squire station wagon makes its way resolutely from the dark gaudiness of Gaslight Square, toward the light.

To read more MIZZOU magazine stories online, visit mizzou.com.

Below: My Romance by Kevin Powers