When John Neihardt joined MU’s faculty 70 years ago, this charismatic poet not only beguiled legions of students with his epic tales of the frontier but also helped forge the voices of talented young authors, including William Least Heat-Moon, who went on to write the bestseller Blue Highways. In the 1960s, well into his ninth decade, the national spotlight shone on Neihardt when his Black Elk Speaks struck a cultural chord and became a spiritual guide to a new generation. This dirt-street scholar, a lover of wide open spaces and the audacity it took to master them, could with equal aplomb navigate the Missouri River, commune with a cousin of Crazy Horse and make literature to immortalize it all.

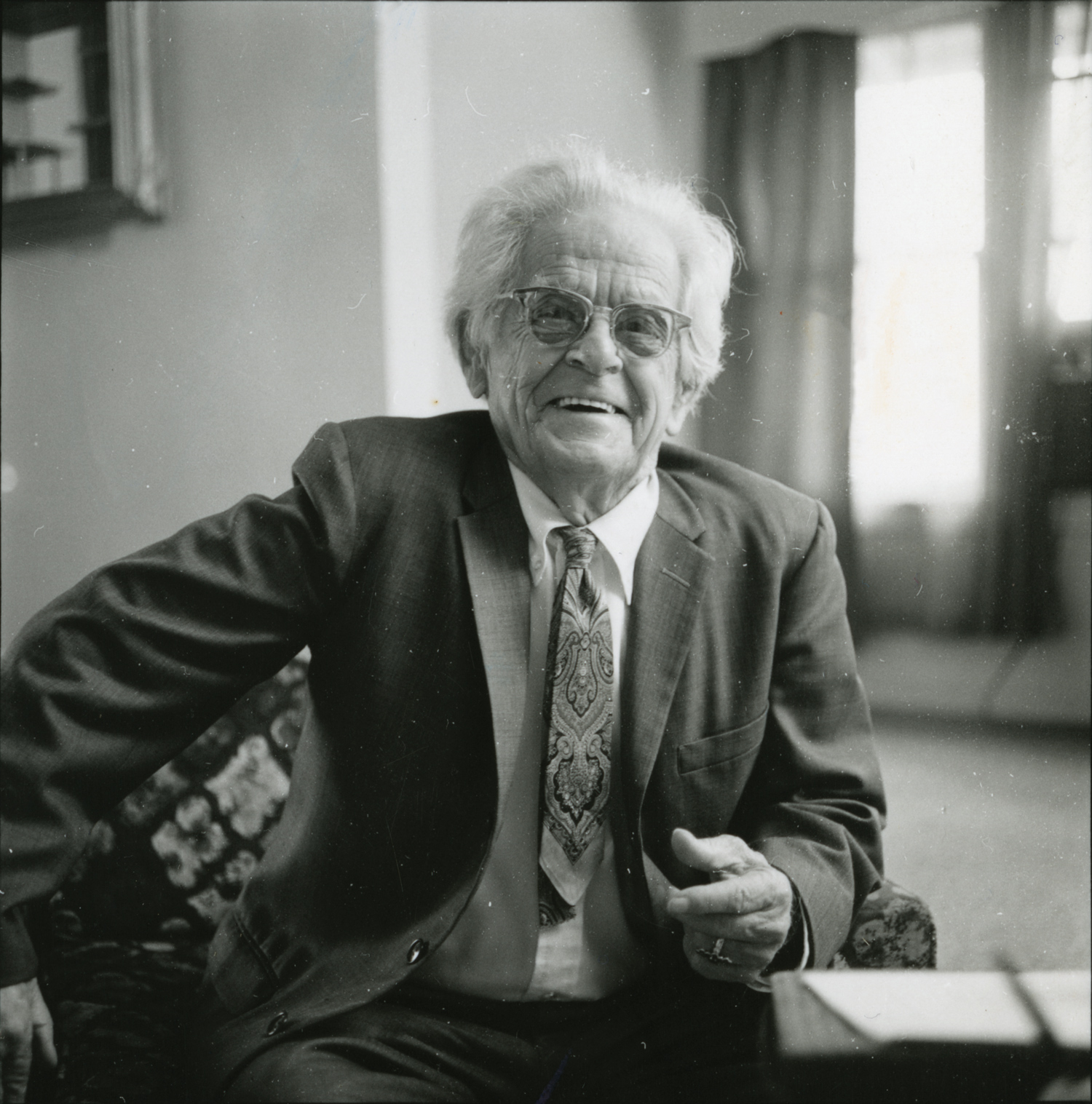

In the spring of 1949, a diminutive man named John G. Neihardt — barely 5 feet tall with a shock of buoyant white hair and a blue serge suit — perched himself casually on the edge of his desk at Mizzou and began performing a course he called Epic America. The lectures were based on his life’s work, a series of five “songs” or “heroic narrative poems” called A Cycle of the West, written at a pace of roughly three lines a day between the ages of 31 and 60, “designed,” he wrote, “to celebrate the great mood of courage that was developed west of the Missouri River in the nineteenth century.” With the last song several years behind him now, and the Macmillan Company promising to publish the cycle in full, Neihardt turned “with great enthusiasm” (and a long wooden pointer) toward that which he had once considered the “backwaters” of creativity: academia.

Students campuswide soon relished their encounters with the Hobbit-like bard in browline frames, an epic written in his wrinkles, in the way he carried himself, small but mighty, like the amateur boxer he once was, so many years ago. “For a poet,” his daughter Hilda would later write, “John Neihardt was unusually physical.” She claimed that, as a younger man, “he could lift his own weight — 125 pounds — over his head with one arm.” Due to his reputation as an easy grader and exceptional storyteller, his voice animated by grit and gusto, his crooked fingers galloping across the oaken desk, Neihardt’s course routinely attracted more students than the largest room in the Arts and Science Building could accommodate. In 1952, in fact, so many students were unable to enroll in Epic America that they petitioned the university to repeat it the second semester.

“Indeed, I do often think of the good days when we were together in Epic America and the meals we shared,” wrote Earl Thompson in a letter to Neihardt in December 1972, not long before his first novel A Garden of Sand was named a finalist for the National Book Award. Thompson, a former student, then listed three things in his life that “shaped his soul”: his grandfather, his children and “the words and way of seeing” he learned from Neihardt, “which gave shape and understanding [to that] which was before stubborn intuition and enormous lonely aches.”

In his nearly spiritual admiration, Thompson — whose often-explicit work couldn’t have been more different from his mentor’s — was hardly alone, especially amongst former students and would-be writers. Neihardt continued teaching Epic America at Mizzou for the next 16 years, but those who encountered the new poet-in-residence upon his arrival at the university had little idea where he had been or where he was soon to go. Few knew of the Pulitzer whispers or his crusade against modernist poetry, of his career as a literary critic or his bent toward the mystical, of the fever dream that sparked his “cosmic awareness” or his friendship with Black Elk, a Lakota holy man whose “great vision” he broadcast around the world. In the beginning, few of them knew what fueled his “words and way of seeing” or from what ancient stardust this Midwestern mahatma must surely have risen.

“Here is a man greater than his works,” wrote M. Slade Kendrick, a friend and economics professor at Cornell University, in 1971. “ … To know him is to forget his short stature and to see that he is truly a moral and spiritual giant.”

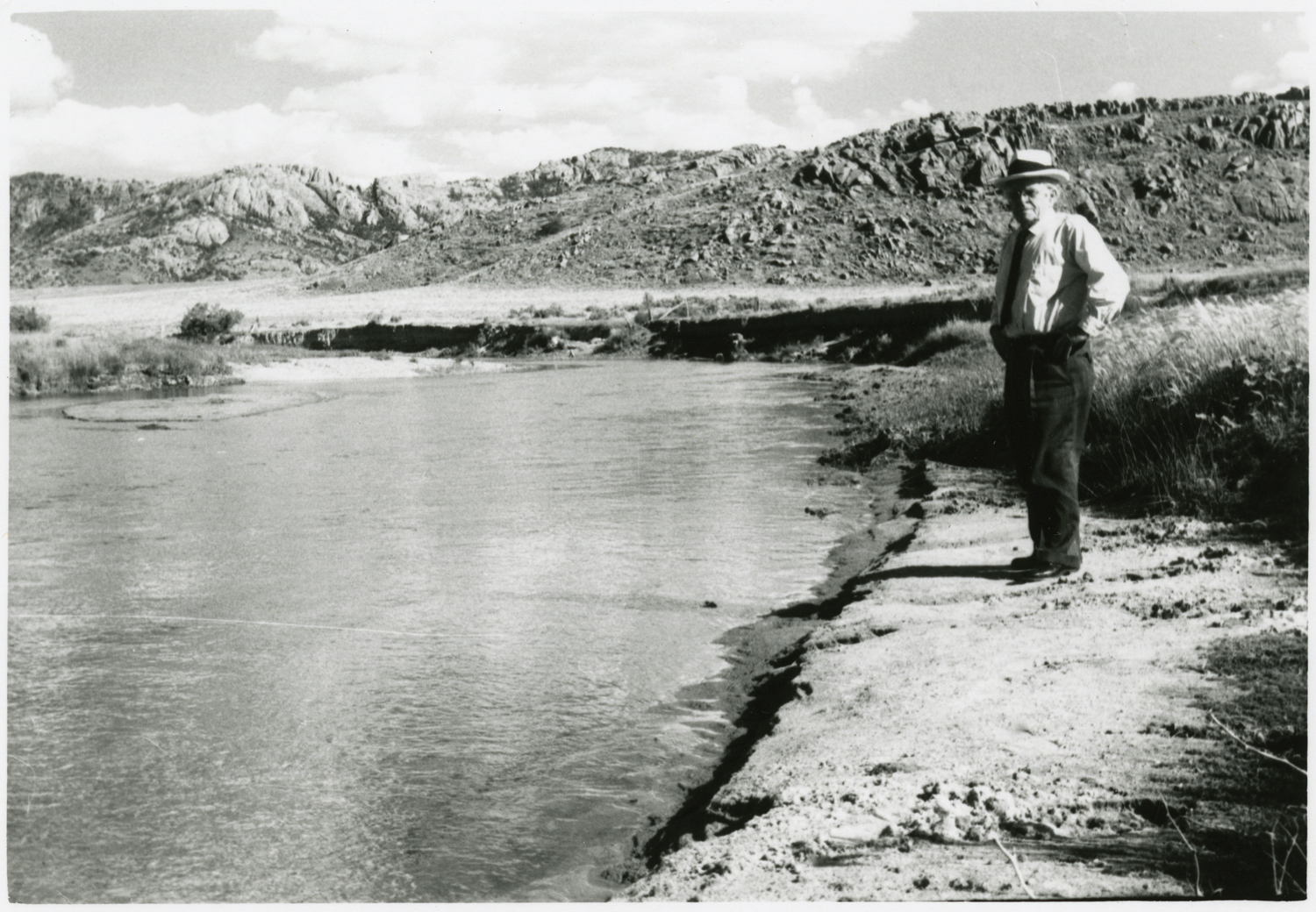

Born Jan. 8, 1881, in a two-room shack on a windswept farm in central Illinois, Neihardt moved with his mother and two older sisters first to Springfield, then to the scorched plains of north central Kansas, and finally to the gristle and grind of Kansas City. They were chasing his father, Nicholas, a loving but restless soul, “a V-shaped little giant of a man” who leapfrogged from one blue-collar job to the next. From a bluff overlooking the flooding Missouri River, the city belching behind them, Neihardt held tight to his father’s forefinger and — at just 6 years old — caught his “first wee glimpse into the infinite.” The experience of such “elemental grandeur” stoked in Neihardt a sense of wonder that never left him, a sort of Old Testament fear he would later depict in The River and I, a travelogue detailing his journey down a still-wild Upper Missouri.

“There was a dreadful fascination about it — the fascination of all huge and irresistible things. … Many a lazy Sunday stroll took us back to the river; and little by little the dread became less, and the wonder grew — and a little love crept in. In my boy heart I condoned its treachery and its giant sins. For, after all, it sinned through excess of strength, not through weakness. And that is the eternal way of virile things.”

After finally leaving Nicholas, Neihardt’s mother transplanted the family once again, this time to Wayne, a small farm town in northeastern Nebraska. Neihardt would later call the state his “spiritual and intellectual mother,” for it was here he began to write. It was here his passions bloomed. And it was here, in the fall of 1892, at age 11, the world “tottered and began to rotate” and he experienced a vision — in the grip of a high fever — that shadowed him forever after.

There was no warning. No parting of the clouds. No tingling in his feet or his fingers. Just “blackness,” he later recalled in his 1972 memoir, All Is But A Beginning. He drifted in and out of consciousness, could trace — just for a moment — the blurry outline of his mother above his bed, could feel the cold cloth she pressed to his forehead. He strained to beckon her, but in doing so she became someone else, someone he didn’t know. She “slowly dissolved,” he wrote, and in the next moment, still untethered, he tore through an emptiness with arms outstretched like a diver.

“There was vastness — terribly empty, save for a few lost stars, too dim and wearily remote ever to be reached. And there was dreadful speed, a speed so great that whatever lay beneath me — whether air or ether — turned hard and slick as grass. I wanted to rest. I wanted to go home. But when I cried out in desperation, it seemed a great Voice filled the hollow vastness and drove me on. There was something dear to leave behind, something yonder to be overtaken. Faster! Faster! Faster!”

His fever broke the next morning, but the dream — like that first gulp of the Missouri — forever changed him. Although he still found time for childhood shenanigans, Neihardt fixated on the notion of leaving something of himself behind, a “worthy work” to compensate for his many blessings. Not yet a teenager, Neihardt possessed the raw material that would compose the rest of his storied career: an epic sense of being and a contract with the cosmos to make it tangible.

Simply put: Neihardt felt destined to become a poet.

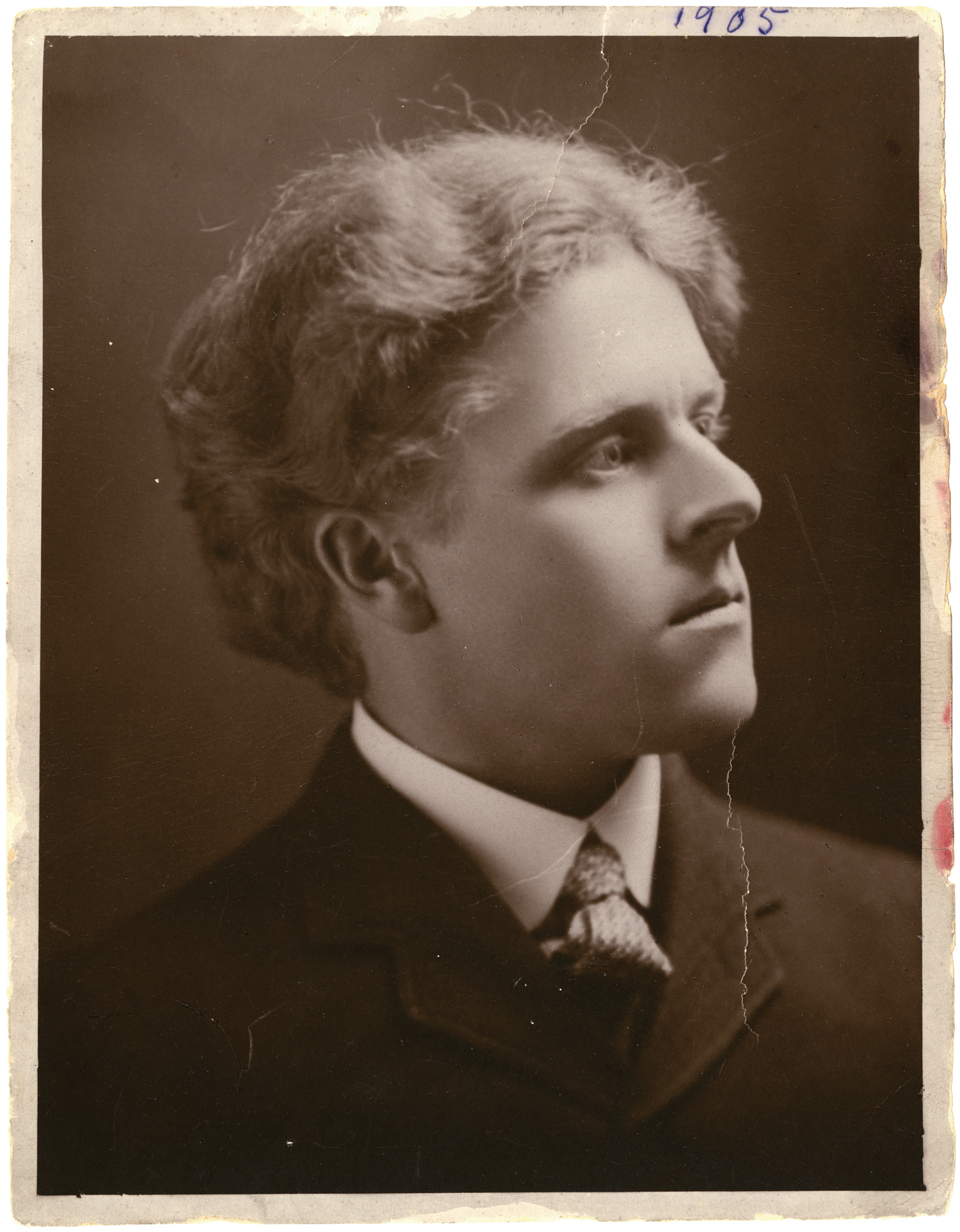

When he was 13 years old, he enrolled in the Nebraska Normal College in Wayne, paying for his tuition by ringing the campus bell. At 15, he earned a teaching certificate; at 16, when most boys his age were still chasing girls and reconciling their hands with their feet, he graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree. All the while, inspired by Alfred Lord Tennyson and Robert Browning, the young scholar wrote poetry — as flowery and contrived as one might expect of a beginning poet and painfully sincere. As a kid, he later wrote, he lived dual lives: one the carefree existence of youth, the other dreadfully preoccupied with his newly ordained purpose. He later memorialized these awkward years in The Poet’s Town. One stanza details the ache of his unmet potential and the alienation imposed on the small-town romantic, a symptom, ultimately, of his command from above:

“Then what of the lonesome dreamer

With the lean blue flame in his breast?

And who was your clown for a day, O Town?

The strange, unbidden guest?”

He completed his first book, a 10-part narrative poem called The Divine Enchantment, based on Vedanta philosophy and his own fever dream, while teaching at a small country school nearby. He was just 17, and though the reviews were middling at best — years later, in fact, he would burn the few remaining copies in disgust — they were enough to justify his ambitions. He soon quit teaching, moved 40 miles southeast with his family to Bancroft, Nebraska, near the Omaha Reservation, and began writing full time, fully submitting to his vision. Over the next two decades, Neihardt completed the bulk of his life’s work: two novels, dozens of short stories and magazine articles, all of his critical reviews for The New York Times and the Minneapolis Journal, and half of the cycle, that “worthy work” he would leave behind, a paean to his dogged western heroes, to Jed Smith and Hugh Glass, to Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull, and what he called a “genuinely epic period.”

“It was a time of intense individualism, a time when society was cut loose from its roots, a time when an old culture was being overcome by that of a powerful people driven by the ancient needs and greeds,” he wrote in the introduction. In approaching the cycle, he wrote, “There has been no thought of synthetic Iliads and Odysseys, but only of the richly human saga-stuff of a country that I knew and loved, and of a time in the very fringe of which I was a boy.”

Out of necessity, he was a prolific prose writer — the mountain of his papers alone, housed at the State Historical Society of Missouri, proves as much — but when it came to poetry, there was no rushing divine inspiration. No shortcuts for what he called the “spiritual progression onward to the loss of the sense of self in cosmic awareness.” It often came at a glacial pace, or not all. The idea for The Song of Jed Smith, for example, the third in his cycle, took 20 years to fully “ripen.” He never wrote when he was “the least weary” and only between 8 a.m. and noon, and even then, he admitted, “doing these things has always been for me something like dying slowly.” More than three lines a day was a bumper crop and only with his wife Mona’s

approval did he consider them finished.

“He said she had that ‘indefinable something called taste,’ ” says Alice Thompson, the youngest of their four children, now 97. “She used to embarrass us because she was so terribly frank. He’d read something to her, and if she praised it, he knew it was good. If she didn’t say much, it wasn’t too good.”

Since childhood, Neihardt had poetized largely in the form of his idols, spicing his verse with meter and rhyme. But following an epistolary feud with Harriet Monroe, the founder and editor of Poetry: A Magazine of Verse, Neihardt quickly fortified his instincts with a critical philosophy of the form. Irked by Monroe’s lackluster response to a hulking 700-line narrative poem he called The Death of Agrippina, and even more by her glaring fancy for the free verse of his contemporary Ezra Pound, Neihardt commenced what became a lifelong campaign in support of traditional poetic form. True to fashion, he conjured the cosmos in his defense.

“Form is not free and cannot be so conceived,” he wrote in his column for the Minneapolis Journal, addressing what he once — in a rare show of cynicism — called “Ezrapoundism.” “It was not through whim or chance that poets first chanted in rhythm; it was not through mere whim that rhyme was invented. Rhyme and rhythm came about naturally, in accordance with the universal tendency of power to return upon itself, to make cycles.”

The campaign ensured that Neihardt remained “always outside the mainstream,” writes biographer Timothy G. Anderson in The Lonesome Dreamer. Nevertheless, Neihardt continued to plow forward with his work, growing his readership with every new book and byline, a stubborn traditionalist wielding his mighty pen and fighting the avant-garde from the workaday, manure-caked streets of tiny Bancroft, Nebraska. Whether poetry or prose, his works dripped with bravado, his verbs strutting around the page, always attendant to the physicality of his characters, be they human, beast or the wild, personified landscapes of the west. His account of a violent Missouri River in flood observes how, “A cottage with a garret window that glared like the eye of a Cyclops, trembled, rocked with the athletic lift of the flood, made a panicky plunge into a convenient tree; groaned, dodged, and took off through the brush like a scared cottontail,” he wrote in The River and I.

He often expressed his delight with a single interjection: Bully! He loved the color purple, the surreal mood it seemed to invoke, and he peppered it throughout his work: purple sunsets, purple moonlight, purple distances, “purple like the lips of a strangled man.” He wrote with an earnestness nearly unheard of today, a narrative voice that spoke sincerely or not at all. At times the effect is an undeniable rigidity, but it can also — at its best — build upon itself until his own epic views inundate and become the reader’s, too, propelled by the rhythm of his verse. Take these lines from The Song of Three Friends, which limns an 1820s St. Louis riverfront scene as a fur trapping expedition embarks for the frontier:

“Behold them starting northward, if you can.

Dawn flares across the Mississippi’s tide;

A tumult runs along the waterside

Where, scenting an event, St. Louis throngs.

Above the buzzling voices soar the songs

Of waiting boatmen — lilting chansonettes

Whereof the meaning laughs, the music frets,

Nigh weeping that such gladness can not stay.

In turn, the herded horses snort and neigh

Like panic bugles. …”

In July 1930, still chipping away his pièce de résistance, Neihardt drove to the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. He had just begun work on The Song of the Messiah, the last in the cycle, focused on the Ghost Dance Movement and the downfall of the Plains Indians, and he was looking for “some old medicine man who might somehow be induced to talk to me about the deeper spiritual significance of the matter.” The authorities at Pine Ridge directed him to Nicholas Black Elk, a Lakota holy man and second cousin to Crazy Horse who, like Neihardt himself, had experienced “a great vision” as a young boy, a dream that prophesied the struggles the Sioux would endure. After completing his interviews, Neihardt wrote, “There was often an uncanny merging of consciousness between the old fellow and myself.”

Whether he simply transcribed the interviews or embellished them for dramatic effect — scholars debate the authenticity of the narrative — Neihardt published Black Elk Speaks in 1931, removed altogether from the cycle. Like most of his previous work, the reviews were appreciative, if never quite heralding an American Homer. In fact, though success never seemed to resemble what Neihardt imagined, his works hardly went unrecognized. In 1919, his Song of Three Friends won “Best Volume of Verse” from the Poetry Society of America. In 1921, the Nebraska Legislature declared him the state’s first poet laureate. He received numerous honorary degrees, busts and plaques were erected in his honor, and in 1935, following publication of The Song of the Messiah, the National Poetry Center in New York deemed him “foremost poet of the nation” with the gold scroll medal of honor. In reviewing the book, critic John Holmes at the Boston Evening Transcript even wrote that if Neihardt, upon completing his cycle, didn’t win the Pulitzer Prize, it would discredit the award. “The prize was created for such a work,” Holmes wrote.

Yet when The Song of Jed Smith was finally published in 1941, Neihardt not only failed to receive the Pulitzer, but also the significance of the cycle’s conclusion registered as merely a blip on the literary radar. Even the Macmillan Company, his longtime publisher, procrastinated in publishing the

cycle in full. His previous accomplishments, numerous as they were, did little to buffer his disappointment.

“My chief life work, A Cycle of the West, to which I had given my most vital years, had been completed and was like a voice that had fallen echoless upon empty air; and there was nothing to fill the emptiness it had left,” he later wrote. “It was as though I had died without the comfort of a funeral, and had to go on playing that nothing unusual had happened. “Apparently there was one of two things I could do,” he added. “Honestly acknowledge my virtual decease, or begin a new life.”

When the University of Missouri came calling, he said yes.

Not long after accepting Mizzou’s offer, Neihardt purchased a small acreage 7 miles north of Columbia. He called it Skyrim Farm and built a Sioux prayer garden like the “sacred hoop” in Black Elk’s vision: two paths — the good red road and the fearful black one — crossing in the center and a tree flowering between them. He often invited his students to the home, where he and Mona hosted them for dinner and roaming fireside chats. He called the students of this generation the “new long hairs,” referring to their spiritual sensibilities, not so different, he believed, from many of the “old long hairs” he had befriended amongst the Omaha and Lakota Sioux. Not so different from Black Elk. Not so different from himself.

“This ‘younger generation’ in which I claim honorary membership, regardless of my years, is caught up in the greatest social revolution the world has ever known,” he wrote in All Is But A Beginning. “ … Surely there is more than frivolity and fashion in their hirsute excesses, more than clowning in their irreverence for the Established and the smug.”

Already hugely popular, Neihardt’s Epic America course grew more competitive still following the reissue of Black Elk Speaks in 1961 by the University of Nebraska Press. Most who encountered the reissue had never heard of the book, but given the burgeoning counterculture movement, “the timing of the new edition couldn’t have been better,” Anderson writes. Just as American youth were beginning to question the Establishment, Black Elk Speaks lamented a freedom and philosophy lost to the very same. Just as American youth were developing a new environmental ethos, Black Elk Speaks promoted a harmony between man and nature, between the “two-leggeds” and the “four-leggeds.” The book exploded, many considering it an instant religious classic, and Neihardt himself was quickly becoming, as one journalist wrote, “one of the authentic legendary folk heroes of our time.” In 1971, Dick Cavett, a fellow Nebraskan, invited him on his late-night talk show. As he often did before his students, Neihardt began reciting part of the cycle, the words punctuated by swift and

labored breaths, head bobbing to his own theatrical rhythm. The next week alone he sold more than 16,000 copies of Black Elk Speaks.

“Black Elk wanted me to take his message out to the world,” he told the Omaha World-Herald. “We were just 40 years too soon.”

Finally, well into his 80s, Neihardt’s work was gaining the audience he’d always imagined. One of those new readers was a graduate student named William Least Heat-Moon, who taught an English course in the same building and would often eavesdrop on his lectures from the hallway. Heat-Moon recalls that he was just beginning to explore “that minor part of my genetics that comes from the Osage,” and given that the Lakota and Osage share a common language, he thought Black Elk Speaks might help usher him forward. But the book sat on his shelf, mostly unread, until 1978, the year he lost his teaching job and decided subsequently to travel America’s backroads, for “a man who couldn’t make things go right could at least go,” he later wrote in his bestselling travelogue, Blue Highways: A Journey Into America.

He packed two books: Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman and Black Elk Speaks by that curious little man so excited about the American West, that sagely old professor who died five years before, at 92 years old, of natural causes. “I was being set up, though I don’t think I knew it,” he says. To read Whitman on the road was a journey into himself. To read Neihardt — to read Black Elk — was something quite the opposite, a journey into “otherness.”

“And that’s when I realized the problem with my life, the reason I was 38 years old and living out of the back of a truck unable to get a teaching job, unable to get any kind of a job, is that I was too self-absorbed,” he says. “The disease of our time.”

Certainly, the lonesome dreamer would have agreed. Despite his failing sight late in life, Neihardt continued a robust correspondence with many of his closest friends until the very end. In his most vulnerable moments, he focused not on his verse, not on the cycle or Black Elk Speaks, but on those with whom he had shared a long and

exceedingly happy life.

“We live in a mystery as fish live in water,” he wrote several years before he passed. “What matters most in this world is love.”

About the author: Carson Vaughan’s writing has appeared in The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The Guardian, The Paris Review Daily and Outside. His first book of literary nonfiction, Zoo Nebraska: The Dismantling of an American Dream, was published by Little A in April.

To read more MIZZOU magazine stories online, visit mizzou.com.