Oct. 3, 2018

Dr. George P. Smith was already awake and walking to the kitchen for a cup of coffee Wednesday morning when the phone rang. It was 4:30 a.m., too early for a casual conversation.

On the other end of the crackling line was a call from Stockholm telling him he was among a trio of researchers that The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences had awarded the 2018 Nobel Prize in chemistry.

For a moment, the 77-year-old Curators Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Biological Sciences at the University of Missouri thought the call was a prank, a common spoof among scientist friends. But the line was too scratchy to be anything but real.

“I kind of knew it wasn’t any of my friends because the connection was so terrible,” Smith recalled with humor. “I mean, Sweden is a really advanced country, but I think they need some work on their phones.”

World-class breakthrough

Smith is the first MU professor to receive a Nobel Prize for his work conducted at MU. His achievement — dubbed “harnessing the power of evolution” by Nobel officials —also represents the first Nobel Prize awarded within the University of Missouri System. His research has led to the production of new antibodies used to cure metastatic cancer and counteract autoimmune diseases, among other things.

MU Chancellor Alexander N. Cartwright said Smith’s work demonstrates the scholarship that Mizzou is doing to change the work through a commitment to excellence and innovation.

“MU faculty are shaping how research is conducted and how advancements are made in the world of research,” Cartwright said. “As the state’s flagship, research and land-grant university, MU’s talented researchers work hard every day to bring expertise to critical needs. The Nobel Prize represents Dr. Smith’s valuable contribution to the university over his 40-year career.”

Smith shares the prize with two other researchers — Frances Arnold of the California Institute of Technology, who was awarded half of the 9-million-kronor ($1.01 million) prize, and Gregory Winter of the M.R.C. molecular biology lab in Cambridge, England, who splits the other half with Smith.

‘This is what we do at Mizzou’

News of his prize spread quickly across campus and by late morning, Smith had already been invited and later joined students in a general genetics class whose excited professor was thrilled to have her students interact with a world-class researcher.

Pat Okker, dean of the College of Arts and Science, said Smith’s generosity with his time and talents speaks volumes about the university’s mission.

“This is what we do at Mizzou. We make sure our students — our undergraduate students and graduate students — have access, direct access, to researchers, even on the day they win the Nobel Prize,” she said. “I mean, you can’t script that any better.”

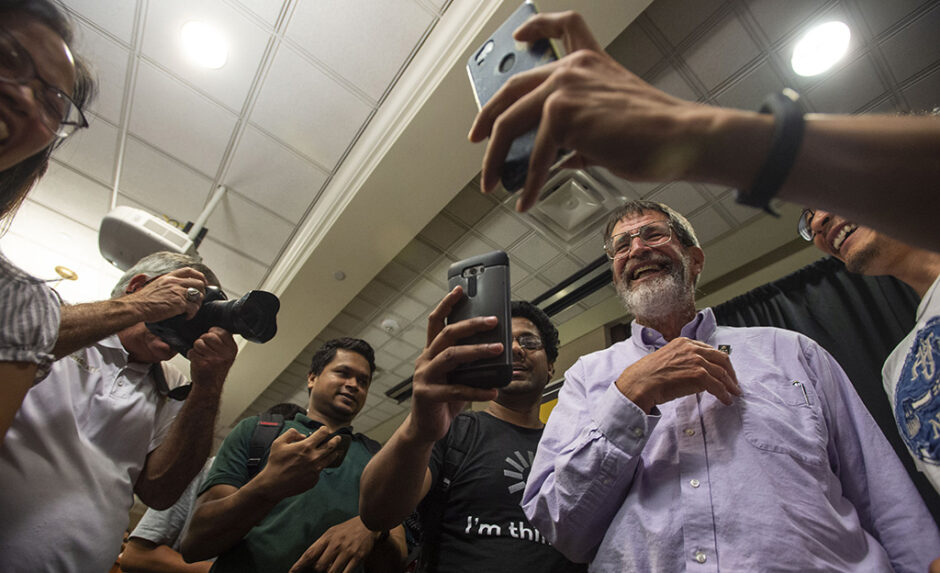

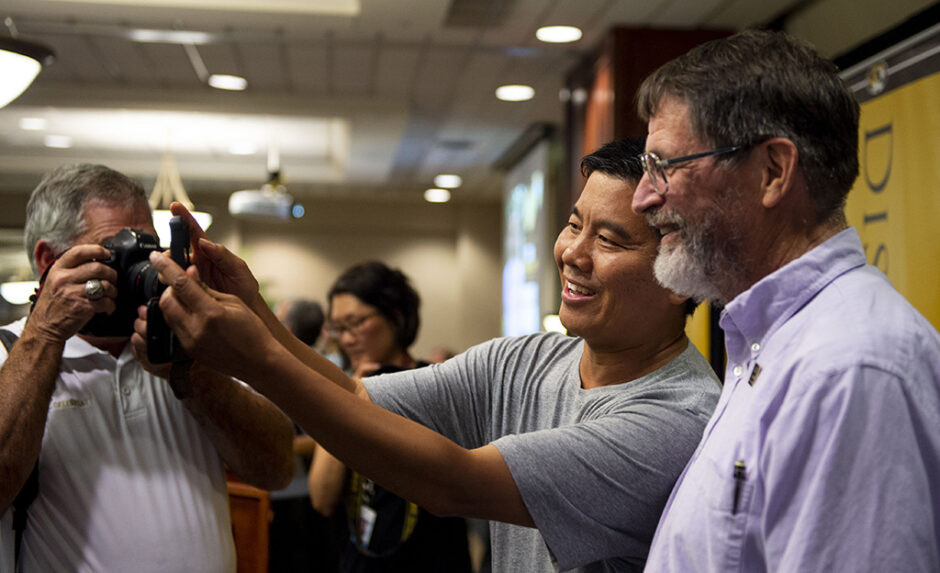

By late afternoon, Smith was on his way to a reception and media event at the university’s Memorial Union where throngs of enthusiastic students, faculty and staff mobbed the unassuming scientist for more than 30 minutes. The crowd of more than 300 crammed into the room for a glimpse of the prize winner, and some held cellphones in hopes of shooting a selfie with Smith in the background.

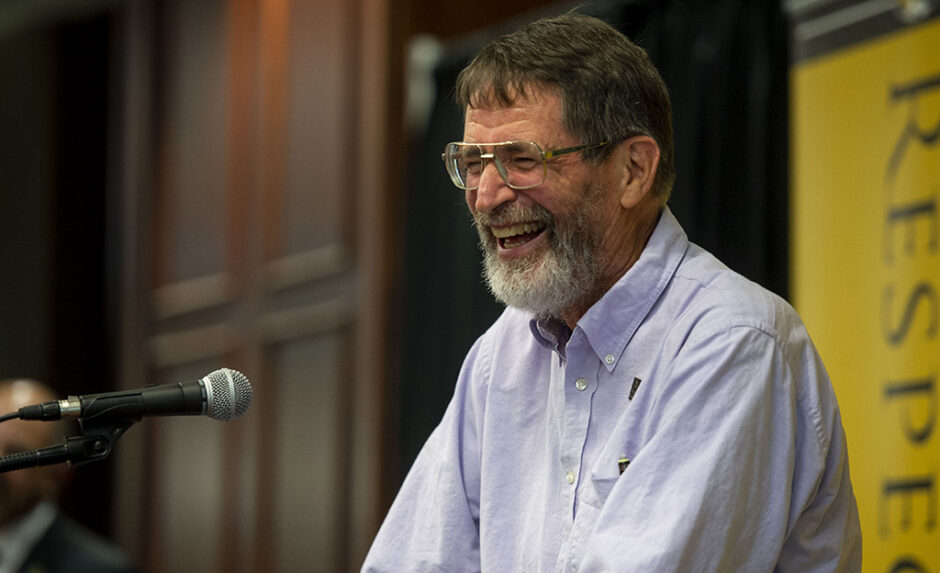

Highlights from the campus reception and media event

Watch the entire reception and media event here.

A modest man by nature, Smith reminded the audience that science is a web of ideas and that breakthroughs come as the result of many scientists’ work.

“I don’t know if I particularly want to say that I am proud personally of this award because as I think all Nobel laureates understand, they are in the middle of a huge web of science, of influence and ideas, of research and results that impinge on them and that emanate from them,” he said.

'Tackling the grand challenges'

Smith acknowledged his work developing phage display, which allows a virus that infects bacteria to evolve new proteins, but was emphatic that he could never have imagined how it would be applied to result in improved treatment of cancer and autoimmune diseases and even to help locate stress fractures in steel.

“I happened to be in the right place at the right time to put those things together,” Smith said. “I am getting an honor that has been earned by a whole bunch of people.”

UM System President Mun Y. Choi said, Smith’s recognition is “a testament to how UM System faculty are tackling the grand challenges facing Missourians, the nation, and the world. The Nobel Prize represents Dr. Smith’s decades of hard work, innovation and leadership in biological sciences and the collaborations he continues to establish worldwide.”

Cartwright said it’s impossible to overstate the importance of Smith’s work and the opportunities he was given at Mizzou to research new ideas. “Our job here is to give people the opportunity to work on new ideas and to think about what they are interested in,” he said. “We don’t know where some of that basic science will lead us when we first start.”

Research rooted in basic science

Smith joined the faculty of the MU College of Arts and Science in the Division of Biological Sciences in 1975. The University of Missouri Board of Curators appointed him a Curators Distinguished Professor in 2000, and he became a professor emeritus in 2015. Smith has focused much of his research on the generation of genetic diversity. He has authored and coauthored more than 50 articles in top scientific journals, and he was selected by the American Society of Microbiology for its 2007 Promega Biotechnology Research Award. He retired in 2015.

“This award, in my opinion, celebrates and validates the impact of basic research, especially research that is interdisciplinary in its focus,” Okker said. “Dr. Smith asked, ‘What would happen if we applied the principles of evolution to the fields of immunology and molecular biology? What he came up with, in terms of an answer, is a method called phase display, the applications of which are far greater than any one person could ever have imagined.”

Smith talks about his lifelong of science and his time at Mizzou

Smith was born in Norwalk, Connecticut, in 1941. As a boy, Smith was fascinated with the natural world, especially reptiles. His favorites were alligators and crocodiles. His parents were exasperated during trips to the zoo where their son spent hours studying animals that didn’t move.

“They were bored out of their skin,” he said in an interview with MU’s NPR station, KBIA.

His interest continued through adolescence and into adulthood. Before going to college in 1959, he was an exchange student in England where he learned to play cricket and rugby, but “not very well,” he said. As an undergraduate at Haverford College in the early ‘60s, Smith witnessed the working out of the genetic code, and his senior project focused on molecular immunology. He received his bachelor of arts degree in biology from Haverford in 1963, and after a year as a high school teacher and laboratory technician, went on to earn a Ph.D. in bacteriology and immunology from Harvard University in 1970. After a postdoctoral fellowship with Oliver Smithies at the University of Wisconsin, he joined the faculty at MU in the mid’70s.

Eventually, Smith developed phage display, which became the center of his work.

Building a legacy in the classroom and beyond

While at MU, Smith trained six postdoctoral fellows, graduated six doctoral students and six master’s students. He taught undergraduate courses and/or labs on general biology, general genetics, basic genetics I and II, molecular genetics, molecular biology, introduction to cell biology as well as senior seminars on biological issues in third world diseases and biological perspective on influenza. He taught graduate-level courses on nucleic acids, cell biology and molecular genetics. As a teacher, Smith was well known for his hands-on learning approaches and critical thinking skills he instilled in students.

“Being at Mizzou, I had a tremendous amount of freedom to explore what I think is interesting,” Smith said. “Not all universities give you the freedom to do that, and I think science really depends on that.”

Smith, a founding member of the Columbia Chorale, lives in Columbia with his wife, Marjorie Sable, professor emerita and director emerita of the MU School of Social Work. They have two sons, Alex, a physician, and Bram, a journalist.