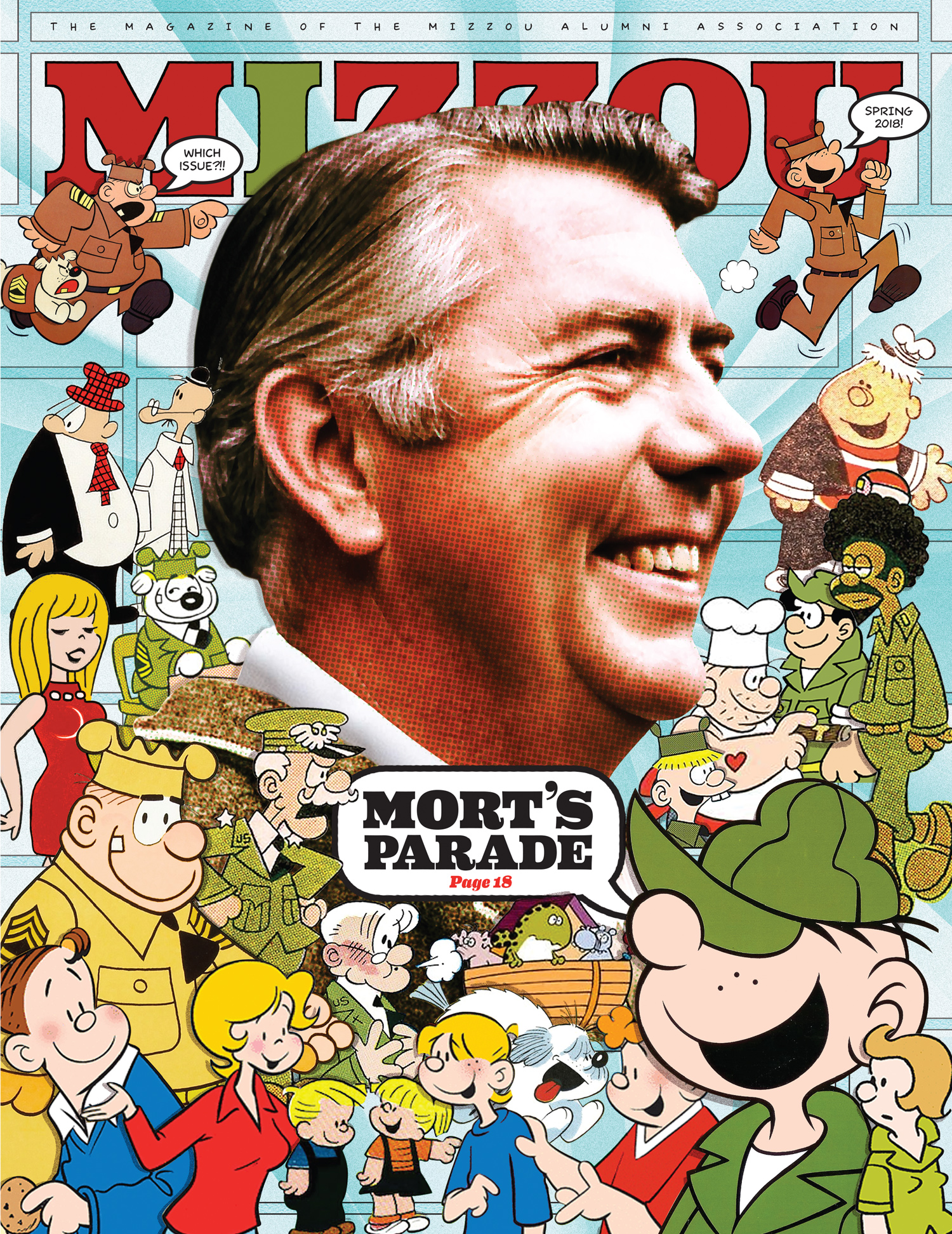

Mort Walker may have created the U.S. Army’s laziest private, but he was the hardest working cartoonist in the business. The Beetle Bailey creator spent nearly 68 years in his studio cranking out six dailies and a Sunday strip, giving him the longest tenure of any cartoonist on his original creation. And with nine syndicated comics in all, he’s one of the most prolific cartoonists ever.

“Old cartoonists never die,” Walker used to say. “They just erase away.” Walker, BA ’48, died Jan. 27, 2018, at his home in Stamford, Connecticut, at age 94. But to millions of readers around the world who chuckle daily at Beetle Bailey — and to the thousands more who stop by the Reynolds Alumni Center to take a picture with the bronze life-size sculpture of Beetle, which was created by his son Neal, or visit the MU Student Center to eat Sarge’s Breakfast Nachos at Mort’s Grill or brainstorm brilliant ideas at the Shack — Walker’s legacy is indelible.

The College Comic

Walker was born in El Dorado, Kansas, Sept. 3, 1923, with ink in his veins. Drawing from the time he could hold a pencil, he sold his first cartoon to Child Life magazine when he was just 11 years old. He realized that, to be a good cartoonist, he needed to be a good writer as well, so he chose Mizzou’s J-School for college. Walker completed one semester before he was drafted in 1942. Stationed overseas at an ordnance depot in Italy, Walker was an intelligence and investigating officer in charge of 10,000 German prisoners of war. Along the way, he sketched constantly, picking up ideas for characters and trying to capture the humor of military life.

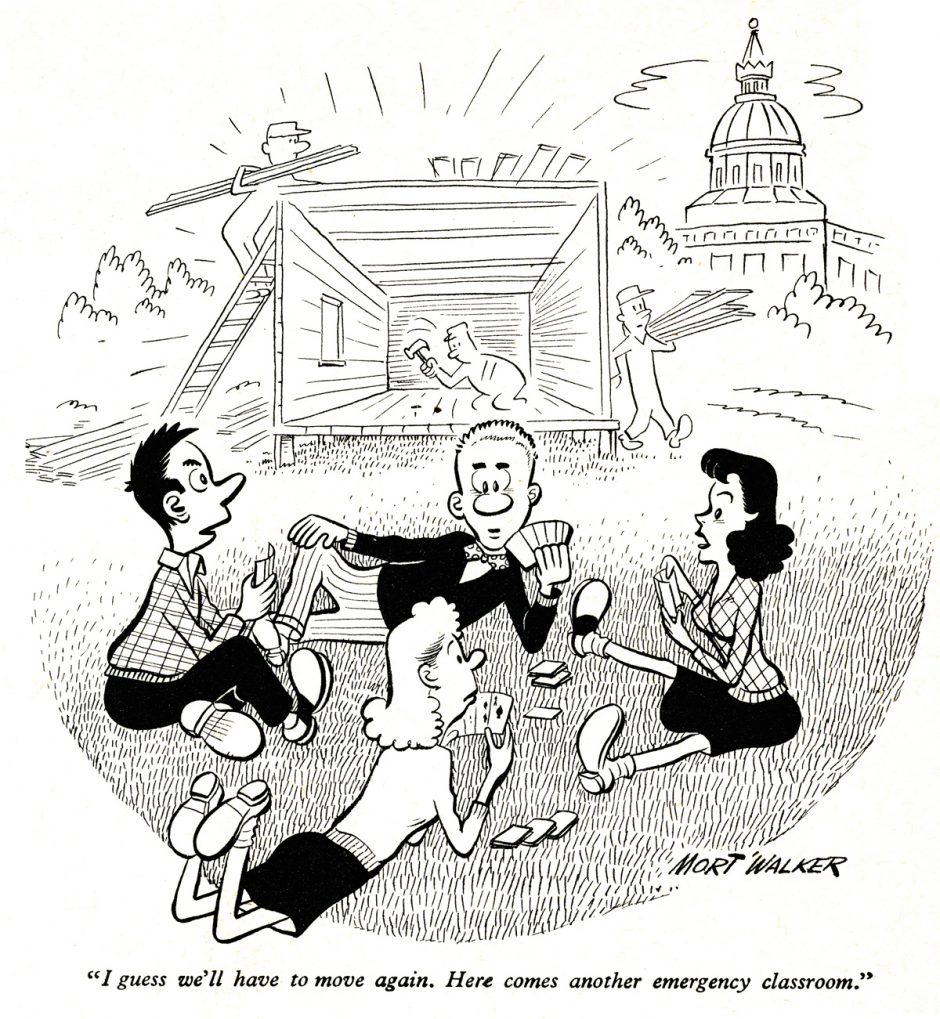

In 1946, Walker returned to Mizzou and joined the staff of Showme, then a drearily dull college humor magazine. Covers were black and white, and inside were full-page essays with no illustrations. From a converted broom closet in Neff Hall, Walker started to shake things up. His first run-in with administration occurred when he satirized claims that campus was overrun with communists: He drew an editorial cartoon showing an American Government class full of Joseph Stalins. Before the magazine was distributed, J-School Dean Frank L. Mott ordered the staff to tear the page out of all 5,000 copies. Shortly thereafter, they arrived at the Showme office only to find they had been evicted — their furniture and files piled in the hallway and the office door locked. Undeterred, they moved staff meetings to the infamous dive bar and campus hangout the Shack.

When Walker became Showme editor in September 1947, he debuted full-color covers and double-page, center-spread cartoons. “Mort was one of those World War II veterans who had a great talent as an artist and cartoonist but who also transformed Showme into a much more professional product,” recalled then–story editor Charles Barnard, BJ ’49. “Needless to say, his drawings were a great asset, but he also gave the magazine a sense of order and format that it had not had. We looked up to him.”

One day, Dean Mott called Walker into his office and told him he wouldn’t be receiving a journalism degree because he hadn’t taken History and Principles of Journalism. “I was too busy saving the world for democracy, sir,” the headstrong Walker remembered replying. The dean not only kicked Walker out of his office but also the journalism school. Walker opted for a degree in humanities, and he didn’t hang around for graduation ceremonies before hopping on a plane to the Big Apple.

A Beetle Is Born

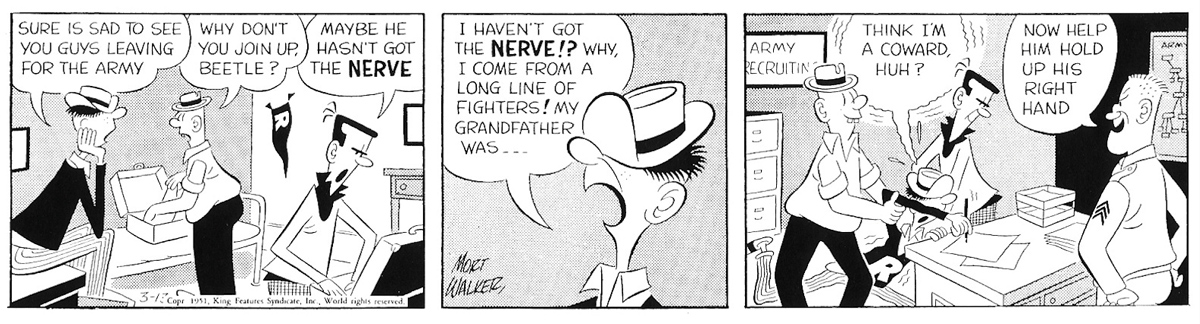

In New York, Walker spent about three years selling cartoons to magazines. One of the editors recognized his work from Showme and hired him to edit humor and cartoon magazines for Dell Publishing. At the Saturday Evening Post, cartoon editor John Bailey encouraged Walker to draw cartoons based on his college experiences. So, Walker resurrected a character from earlier gag cartoons, a goof-off named Spider who wore a hat over his eyes, and he took the strips to King Features Syndicate. King already distributed a strip with a character named Spider, so Walker renamed the character Beetle.

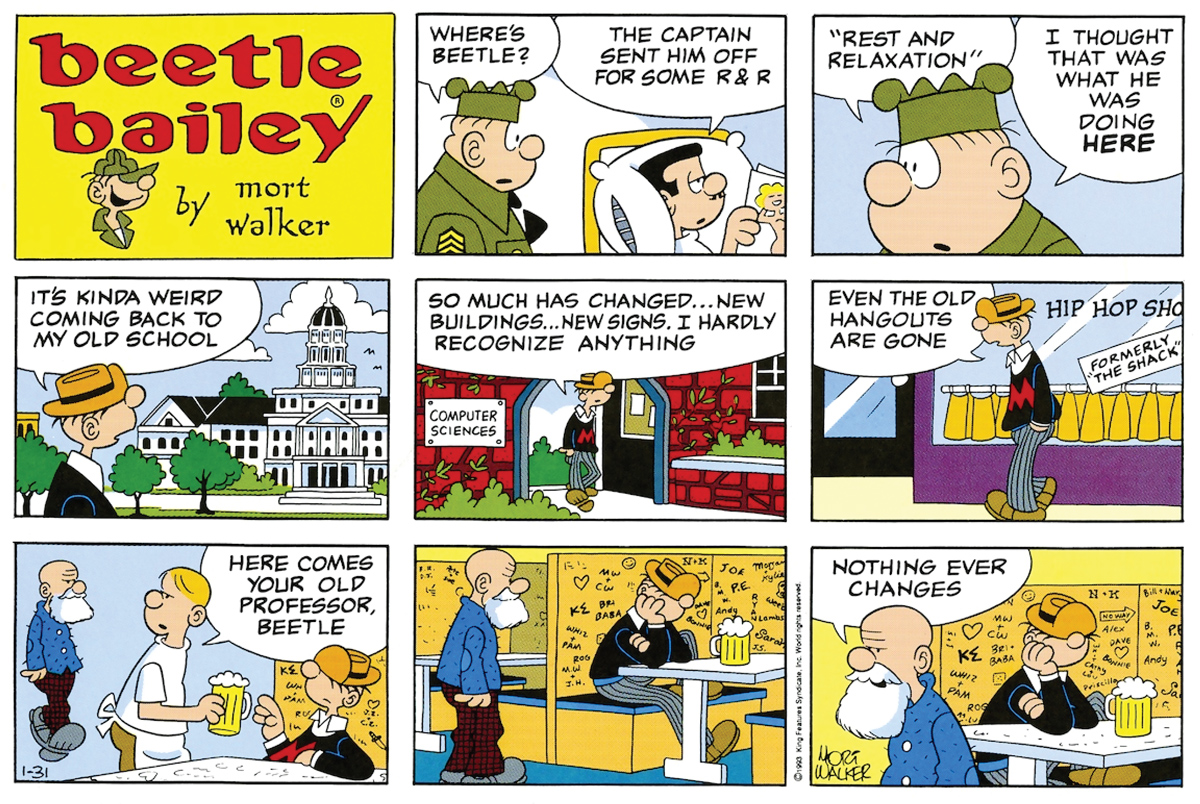

Beetle Bailey launched Sept. 4, 1950, in 12 papers. Although Beetle went to Rockview University, several campus details came right out of Columbia. These included the Shack, Memorial Union and Francis Quadrangle; characters who closely resembled Walker’s Kappa Sigma fraternity brothers; and an eccentric professor named Jesse Wrench. Guided by his motto — “Whenever the urge to work comes over me, I lie down until it goes away” — Beetle’s character began to emerge.

But after six months, only 25 papers carried the strip. A larger population of potential readers had been in the military than had gone to college, so when the Korean War started heating up, Walker enlisted his campus clown in the Army. College comrades became barracks buddies, peculiar professors became strict sergeants, and Beetle Bailey became the perpetual private of the funnies page.

Controversy followed Walker in his new strip when military brass didn’t appreciate him making fun of authority and romanticizing foot-dragging. They banned the strip from the Tokyo edition of Stars and Stripes. But the publicity increased its reach even more. From 1954 to 1968, circulation grew from 200 newspapers to 1,100, according to King Features.

Circulation increased again in the early 1970s when Walker created Lt. Jack Flap, and Beetle Bailey became one of the first established strips to integrate a strong and proud black character into a white cast. “He was a pioneer in reinventing comic strips for new decades and audiences,” says Mark Evanier, a comic book and television writer known for his work on the animated TV series Garfield and Friends.

Critics now recognize that Beetle Bailey was never really an Army strip. “Beetle is essentially a humorous attack on a hierarchical society,” says comics chronicler R.C. Harvey. “Most of us resent people with power and wish we could fight back. Mort made a 68-year career out of fighting back.”

Today, Beetle Bailey runs daily in roughly 1,800 newspapers in more than 50 countries with a combined readership of more than 200 million — and it will continue under the seasoned hands of Walker’s sons Greg, Brian and Neal.

The Funny Factory

The Walker boys grew up in Fairfield County, Connecticut, a hotbed of comic-strip artists, where normal meant cartoons hung on the walls, families received personalized Christmas cards from world-famous cartoonists and fathers worked from home. When their dad wasn’t talking in goofy voices and making funny faces, he was in his studio brainstorming one-liners and sketching strips.

“He was sort of a cartoon character himself,” Greg says. “We’d go into the grocery, and he’d say, ‘I came in here with my wife. I can’t find her. Which aisle do you keep the wives in?’ ”

To make sure he always had enough ideas to keep readers cracking up every day of the week, Walker brought in a team of cartoonists for brainstorming. Over the years, he worked with Jerry Dumas, Bob Gustafon, Frank Johnson, Bud Jones and his longtime assistant Bill Janocha. “It felt like half the comic strip page was Mort Walker and his disciples,” Evanier says. By the mid-1980s, the two eldest Walker brothers were assisting with the production of Beetle Bailey. Every month, Walker, Dumas, Greg and Brian would meet for a gag conference where they’d each bring about 30 ideas to compete for a spot in the strip.

“I remember him telling me, ‘This is Beetle Bailey, not Doonesbury,’ ” Brian says. “His mantra was, ‘Funny pictures. Funny pictures.’ Mort was OK with a corny gag. He had a little bit of that Midwestern sensibility. He understood the common man, and this was the secret to the success of the strip. He wasn’t trying to be too smart.”

Not only was Walker seemingly without competitive ego, but he also was an activist for cartoonists. He served as president of the National Cartoonists Society, and spent 35 years — and millions of dollars — establishing the first cartoon museum of its kind in the world. Today, his International Museum of Cartoon Art Collection, which contains more than 200,000 original cartoons and other priceless objects, is housed at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum at Ohio State University. “He recognized earlier than most people that comic strips embodied so much knowledge about our culture and how it changes, and that this material is just a gold mine for the future,” says Cullen Murphy, author of Cartoon County, a book about the Connecticut cartoonists, and a former writer of Prince Valiant, a comic strip that his father drew.

Mort’s Mizzou

It was to this cultural sensibility that Dean of Students Jeff Zeilenga appealed when MU began planning the new Student Center. “Our students wanted a space that was uniquely Mizzou,” says Zeilenga, who was then the assistant vice chancellor of student affairs. “We also wanted alumni to come back and have this new building remind them of their time at Mizzou,” he says. The Shack may have been a dilapidated fire trap, but students of that era “have fond memories of spending time there with friends, meeting their spouse, carving their initials into the wood.”

And no one is more synonymous with the Shack than Walker. Zeilenga called upon the watering hole’s most famous patron to talk about creating a place that celebrated his time at Mizzou. During the building of the Student Center, Zeilenga would fly to Connecticut, where he and Walker would brainstorm ideas for how to tell stories of his Mizzou years.

In 2010, Walker returned to campus to dedicate the new MU Student Center, complete with Mort’s Grill, a games and grill area, and the Shack, a programming and lounge center. The area contains large images of Beetle Bailey strips, trophy cases of memorabilia and a 6-foot statue of Beetle leaning against the now beer-free bar. “I’m getting a kick out of the fact we’re celebrating the Shack,” Walker told the Columbia Daily Tribune. “It’s like celebrating a Dumpster.”

Of course, the Shack of today is a far cry from the Shack of Walker’s era, but it’s once again an iconic spot on campus. Some of the tables even have the original initials carved in them.

“We’ll have students who come to campus for a visit, and when their parents walk into Mort’s and the Shack, they beg their students to go do the rest of the campus visit while they search for their name carved into the wall,” Zeilenga says.

Walker’s is still there, too.