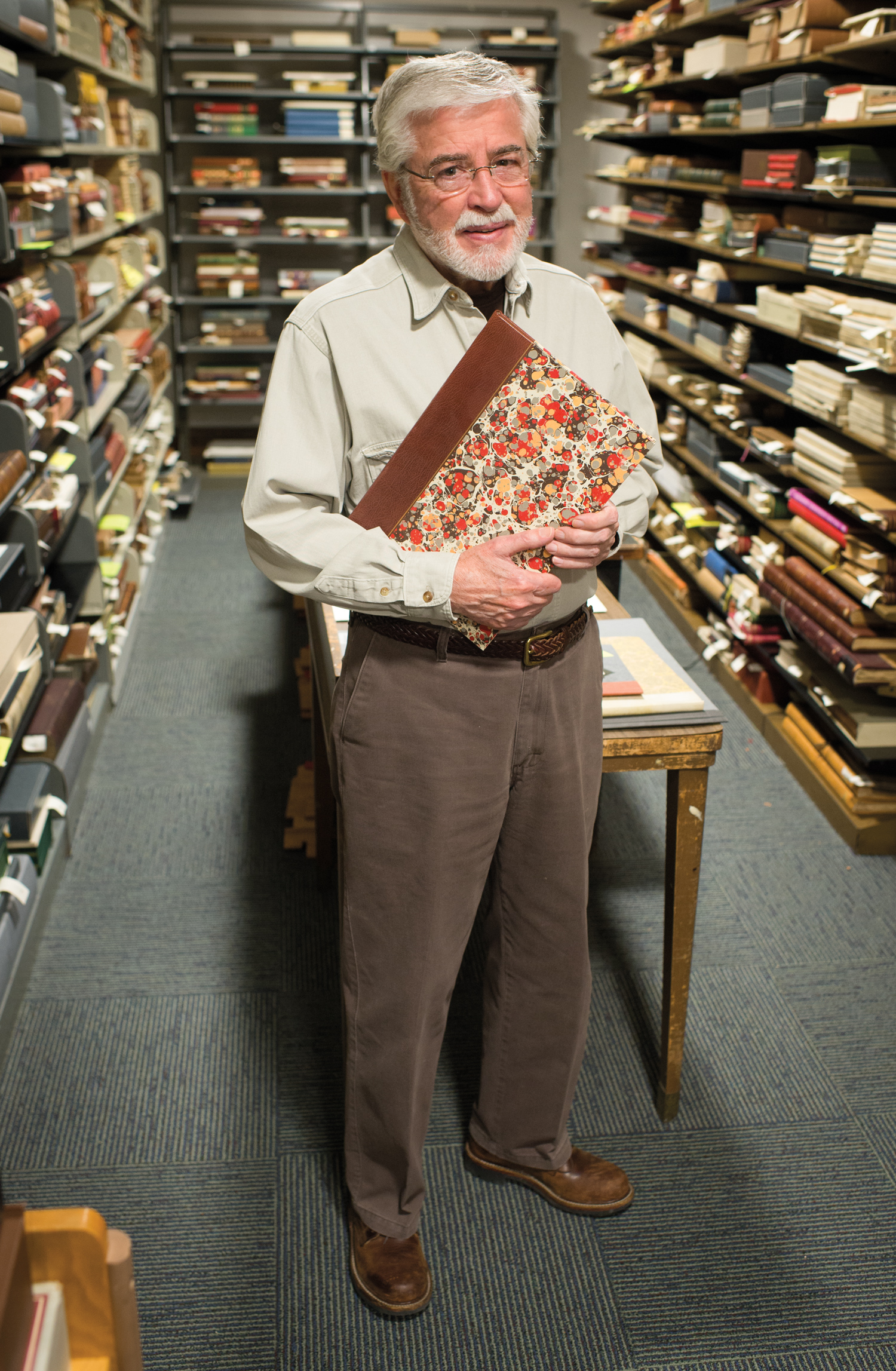

On first hearing, the story smacks of so much over-proud, possibly mythical, family lore surrounding a precocious tot who grows up to become an acclaimed author. But there is the photograph: Wee William Trogdon, age 2, seated on the floor, studying a book — a reader amongst toddlers.

Nevermind that the book is upside down.

“I’ve always had this love of books,” says Trogdon, BA ’61, MA ’62, PhD ’73, BJ ’78, DHL ’11. “It came in the genes. I can’t explain it.”

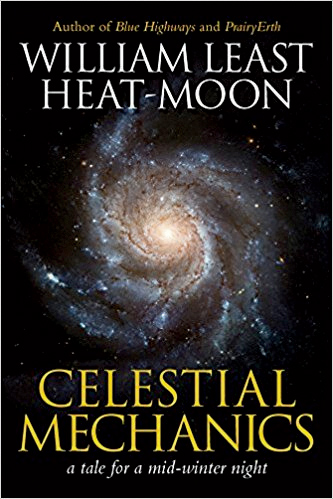

Unexplainable, but fruitful nonetheless. Trogdon, who writes under the nom de plume William Least Heat-Moon, has authored nine books, including the best-sellers Blue Highways, PrairyErth and River-Horse. His new book, Celestial Mechanics (Three Rooms Press, 2017), excerpted on the following pages, is his first novel. Anchored in Trogdon’s experiences and layered with his authorial imagination, he calls the book hybrid fiction.

Despite Trogdon’s bibliophilia, he arrived at Mizzou in 1957 on academic probation, owing to low grades in high school. However, a stratospheric entrance exam score previewed his potential, and soon he was thriving in honors college courses. For Trogdon, campus was embodied by Jesse Hall, where he took classes; the Columns, whose physical presence inspired him; and the library, his sanctum.

In the 1950s, the only freshmen allowed in the library stacks were honors students, Trogdon says. “I remember going through that little entrance on the second floor and seeing the closed stacks for the first time.” He was awestruck. In that moment, Trogdon voluntarily shouldered what felt like an overwhelming responsibility for the hundreds of thousands of volumes hunched under the low ceilings. They were somehow his to read and care for. “Noooooo! I’m doomed,” he thought. “But I loved it.”

Fifty-eight years later, Trogdon formalized that paternal feeling by making a seven-figure donation to Ellis Library. The estate gift goes to a fund for rare books and special collections on American exploration, travel, topography and Native American studies.

If books have requited his affections during a 35-year career in the highest echelon of American nonfiction, they’ve also played matchmaker. He met his wife, author Jan Trogdon, 20 years ago when she was working on The Unknown Travels and Dubious Pursuits of William Clark (University of Missouri Press, 2015). It’s based on a heretofore obscure log William Clark kept of his travels a few years before he and Meriwether Lewis led the Corps of Discovery. MU acquired the logbook for 25 cents in 1928 and housed it, all but unnoticed, at the Western Historical Manuscript Collection within Ellis Library. Jan found the logbook, which led to she and William finding each other, and the rest is nuptial history. Of the library’s treasures, she says, “This one has been discovered, but there must be others.”

The debut novel of best-selling nonfiction writer William Least Heat-Moon, a.k.a. William Trogdon, offers a glimpse into the famous author’s mind. Celestial Mechanics includes the following introduction to protagonist Silas Fortunato, a playwright and astronomer who is falling in love with Dominique Heppermann (Spoiler alert: a proposal is in the offing). In the following excerpt, meet the curious and philosophical Silas, a careful listener and observer. Silas, it turns out, has much in common with Trogdon.

A Double-Bell Euphonium

Silas Fortunato, nearing his thirty-third year, was an ordinary-looking fellow—not handsome, not unhandsome. Perhaps it was his regular features that gave him a kind of universal face, one people weren’t always sure they’d actually seen before. He was clean-shaven although he’d tried a beard, but his chin, poor of follicles, left him not dashing but scraggled. Had he the inclination, his every-man-jack of a mug might serve well in a heist: What bank clerk could put the finger on somebody who’d stand out only if lined up with men of another race or, more usefully, a different species? Trim, nimble, dexterous, having a pleasing symmetry of frame, Silas was neither small nor tall, only medium without being also average. Dressing in earthen brown more than is good for a young man, his dark hair starting to streak with strands of argent, he wasn’t likely to bald. He wore no jewelry, and on him was nothing artifactual unless you count the tiny tattoo of a ship anchor at the base of his left thumb. Rarely did he wear a watch or tote a phone.

Trim, nimble, dexterous, having a pleasing symmetry of frame, Silas was neither small nor tall, only medium without being also average. Dressing in earthen brown more than is good for a young man, his dark hair starting to streak with strands of argent, he wasn’t likely to bald. He wore no jewelry, and on him was nothing artifactual unless you count the tiny tattoo of a ship anchor at the base of his left thumb. Rarely did he wear a watch or tote a phone.

Leery of unmindful use of digital devices and what he sometimes called antisocial media, he accepted the binary realm cautiously by restricting mechanical contrivances to prevent them from constricting him. A habitual traveler of twisting backroads, not for him the information superhighway of factoids and factettes. He saw cyber absorption as a blunting of capacities, a stupefaction requiring an electronic glitch to awaken a twiddler from a synthetic world of trivial connections where excessive interplay numbs communication of significance, a theft of real time on a real Earth, a narcotic for those unable to carry on without a jolt from a battery or a nearby wall socket. He considered spurious the implicit message in a digital linkage: You are not alone. Nor did he trust anything designed to transmute his reality into raw data and transform him into virtual inconsequence. For him, the Internet too easily imperiled discriminating thinking.

It was, in fact, a letter to the Washington Post that led then twenty-year-old Silas toward journalism:

Corp-Power is propelled by its drive for absolute dominion—the creation and control of a universal consumer, even if that pawn has seven billion faces. The way to such an end is through info-mining by search engines. And what is it they search for? Means to direct your spending. To do so, Corp-Informatics must first mine you, while distracting you with gadgets and games. You get gamed into yielding up your confidentials with your own thumbs, allowing your brain to be picked clean of its marketable data— -formerly called your life. Your smartphone and keyboard surrender to Corp-Power your identity. (“Participate in our online customer survey and receive a coupon worth $5 on your next qualifying purchase.”) In the age of punch cards, the battle cry was “Fold! Spindle! Mutilate!” But now, is it even possible to imagine such a cri de coeur?

Some days after their meeting at the Drummer’s Inn, Silas phoned D. E. Heppermann whose first name he didn’t yet know. They met at Bistro Pagliaccio where not long before she’d stood on Ninth Street to look in at the intent diners. Her conversation with him was guarded, Dominique feeling her way until the second pour of Barolo. At a near table a couple squabbled over something on a smartphone, and Silas said,

—People, besotted with pop culture and gizmos, tap on their gadgets as if to make the Universe programmable to their own desires. They walk, eyes fixed on a screen, insulated, oblivious to a deteriorating environment that’ll make their dreams impossible.

—Are you an enviro?

—The great Rachel Carson wrote—this is a paraphrase—The more clearly we focus on the wonders and realities of this Universe, the less taste we have for destruction.

Dominique thinking, What do I have this time? Silas was saying,

—We’re environmentally dysfunctional because we don’t observe or honor our relationship with the Cosmos.

—I have enough issues in my relationship with myself.

Undigitalized though he was—often favoring the happy clackety-click of his portable typewriter to the silence of his laptop—Silas never left home without a pocket compass, one of a dozen he owned. When next they met, Dominique said,

—What’s with the compass thing?

—I like to know where I am.

—That little red needle tells you?

—To a degree, you might say. More so than a watch. How much use—ultimately—is knowing the hour? Clocks are boss machines telling you what you’re running out of. People look at a phone to learn what to do next with their lives.

—That’s the way it is today. Deal with it!

—A compass is proof of existence in a way an hour can never be. A watch stops because it depends on you. A compass never stops because it depends simply on a fundamental power of the Universe: magnetic force. A compass registers cosmic influence, and Earth is the battery.

In her mind: Mom must have dropped him on his head.

—Wherever I am, this device is correct. The hands of a watch don’t move because I move—they move in spite of me. But a compass needle follows me along. Call it more companionable.

—Wherever I am, this device is correct. The hands of a watch don’t move because I move—they move in spite of me. But a compass needle follows me along. Call it more companionable.

—Where do you get this stuff?

—My thoughts wander.

—I’ll say.

—My Swiss grandfather was a young compassmaker who immigrated to America. From Italian-speaking Canton Ticino.

—Yeah?

—A clock can deceive, but a good compass speaks only the eternal truth of magnetic poles. Hours, minutes—they’re necessarily momentary. Give me the precise time, and even before you finish, your answer is wrong.

She took something from a pocket, held it up, and said,

—This is a smartphone. Smart as in knowing stuff. Like the hour or the way to somebody’s front door or who Rachel Carson is.

—If you don’t forget to recharge its brain. And, you’re within range. The range of my compass—which never goes dead—is planet Earth.

—Bravo.

—When Einstein was a boy, his father gave him a compass. Albert later said the mysterious play of the needle started him toward his great theory. Far beyond hours, E equaling mc squared has to do with time. Truly meaningful time. Young Albert never owned a watch.

—Speaking of time.

—An invisible intensity moving the needle convinced the boy of unseen powers in the Universe. Ones like magnetic force.

—Should I be impressed?

Keeping her eyes on him, Dominique listened. This man was different. To life, he didn’t just react—he interacted. He didn’t skim a surface, he entered it—more a diver than a swimmer. Silas was still talking.

—Magnetism—as Plato understood it—he speculated it was divine. He half-realized the Earth, like galaxies, are massive magnets. But our planet’s not much of a clock, although it tells cosmic time pretty well.

—Are you a New Ager?

—Don’t know, but I know hours give a temporal fix. A compass gives a cosmic position. Marcus Aurelius—.

—Marcus who-lius?

—A Roman emperor and philosopher. He said something on the order of, To fail to perceive there’s an ordered Universe is to fail to comprehend where you are. To fail to perceive that order is to be blind to what you are and what the Cosmos is.

—You actually believe a compass would help me know myself?

—And your place in the Universe. Again, to a degree.

—The Universe is on its own.

—In the Navy, we had a slogan—Ship, shipmate, self.

Dominique watched him looking at her, and she said,

—You talk different. Like a professor.

—Maybe because I was one.

—They fired you?

—I hung it up when I realized teaching journalism to undergraduates reflected my praying.

—What’s that mean?

—I was talking to myself.

—That I can understand. I have to ask, are you autistic?

—You like labels? Enviros, New Agers, autistics? Okay. I’m not, but I may have been sourced to the wrong planet.

—Don’t be coy. Speak truth. I dated an Asperger. He didn’t talk normal. Nutty stuff, weird sentences. Low-frequency words.

—My mother deplored inarticulateness. She’d scold me, Don’t abet the corrosion and erosion of our tormented language!

—That’s America. That’s how we do it.

—Well, my mom, you know, actually, she’d like go, Enunciate! Right? And I’m like just, Okay, Mom! And she’s like, Use language to the best of your capacity! And I’m all, God, Mom! But anyway. If, you want, like, I mean, hey! You know, I could like just definitely dial it down, you know, if that’s kinda sorta what you’re totally into. Right? I mean, like, you just gotta, you know, I mean, actually, just like, tell me. Right?

—I was only asking.

—For lovely Dominique, I’ll attenuate my vocabular locutions lest you find me aberrant beyond forbearance.

—Stop it!

—I got you to smile.

Shaking her head, she tried to change the subject.,

—Your silver keyring—a lucky charm?

—Charms are magical thinking. This thing’s the Hopi Maze of Emergence. A simple admonition to keep trying to emerge.

—Charms are magical thinking. This thing’s the Hopi Maze of Emergence. A simple admonition to keep trying to emerge.

—From what? Being a character?

—Blindness. Misconceptions. Misbeliefs. My failures. Almost everything. Maybe even being a character.

When they left Bistro Pagliaccio, a ward of the streets mumbled and raised an open palm, and Silas handed him a two-dollar bill, several of which he carried for tips, and the man returned a suspicious nod.

—Greasing the palm of Saint Peter?

—Easier than greasing my conscience.

—What if it’s only buying off your conscience?

—Couldn’t the world use more buying off consciences?

And so Silas, like the onset of sleep, quietly and imperceptibly came into her life, and it was as if one morning she awoke to find he’d just happened to her.

Over the days, they talked, they appraised each other, and she would tell her sister: He might be out there, but he can get through a date without texting. Dominique had not met a man of real ideas, and she found some of his notions useful. Above all, he never bored her. Free of manipulative lines crafted to deceive, it wasn’t what Silas said so much as his attention to what she said, his listening intently, following her along—or trying to—and when her thoughts ran out, only then did he speak, expressing interpretation without judgment. He listened to her describe her father’s bitterness, her mother’s abused tolerance, her sister’s decision to enter a convent, and especially to her own uncertainties to which he responded with questions: Was a single life inherently one of self-interest and self-indulgence? Can a sense of increasing isolation alter from choice into an identity? A destiny? And self-immersion—does it lead into becoming less communal, less empathetic, more alone?

She began to see, of those who live at another level of perception and awareness, Silas was often among them. He revealed a rare hospitality of sustained listening. Happier to receive words than throw them around to make himself known, he tried, so he said, to practice the art of auscultation. She had encountered enough self-engrossed men whose absorption was so complete it took them but moments after meeting her to sink like a pebble in a puddle.

Rarely speaking in terms of unequivocal solutions, Silas instead would hunt a trace through thickets, on occasion entangling his reasoning; yet to see him think his way back to a trail gave her heart she might learn to do the same. He had confidence from a capacious mind, never totting up scores as did she to figure who was worth her time.

Dominique believed he recognized her latent abilities—in addition to admiring her face and legs—and when he complimented her, it seemed he’d not ever before uttered anything similar. With him she was the only person present, no matter how crowded the room or how attractive the woman at a next table. She calculated he wouldn’t attempt to put one over on her, and she could relax because he was without sneak or ridicule.

Having no need to steer him, when a troubling situation did occur, Silas had a plan often smart, sometimes whimsical, but never unconsidered or hopeless. Testing him by half-revealing a piece of her past to observe how he treated it, not just then, but in ensuing days, she watched for exploitation of his knowledge of her. In a coarse age, he was a civil man who wouldn’t force her to fight for her life.

Both men and women responded warmly to Silas, they too noting he was without guile even to the point of his striking some as being naive as well as singular. Although poor with figures—uncertain how many aughts to include in an answer when multiplying numbers ending in zeros (Twenty thousand times two million, is it forty million or forty billion?)—he was a good psychological mathematician able to add up character and motivation. If Dominique lacked a capacity with people, that was it: adding them up. But one evening in Pagliaccio’s, she warned him,

—If you ever get the idea you understand me, then you have no understanding.

—Ah, to be un-understandable! Sweet mystery of life at last I’ve found thee!

—What?

—It’s from an operetta. Naughty Marietta.

When their drinks arrived, she said,

—Are you staring at me?

—I’m not staring.

—I think you are.

—Under the gaze of such dark eyes, what can a man do?

—You tell me.

—Tell you what?

—How about I’m tough?

—Could be your middle name.

—Thank you.

—Welcome.

—Next time, don’t make me drag compliments out of you.

—Easily done.

She raised her glass,

Books by William Least Heat-Moon

Blue Highways: A Journey Into America, 1983

PrairyErth (A Deep Map), 1991

River-Horse: The Logbook of a Boat Across America, 1999

Columbus in the

Americas, 2002

Roads to Quoz: An American Mosey, 2008

Here, There, Elsewhere: Stories from the Road, 2013

An Osage Journey to Europe, 1827–1830, 2013

Writing Blue Highways: The Story of How a Book Happened, 2014

Celestial Mechanics: A Tale for A Mid-winter Night, 2017

—Here’s to confiding a single thing about yourself nobody else remembers.

—If I can think of one. I’m hardly a closed book, despite all of them on my shelves.

To retrieve something only he remembered, he studied the ceiling painted with a caricature of a tearful clown, then said,

—Here’s an amusing word—twelfth. Say it aloud six times.

—Try again.

—In high school I was manager of Adam Wang’s rock band, Adam and the Electrons. A girl told him it was a stupid name, so he asked me to invent something real kick ass. His terms. I suggested Gone Fission. They sold nine or ten CDs.

—Keep trying.

—When I was a boy, my uncle taught me to carve decoys from basswood. After a half-dozen, I finally made a green-winged teal I saw as perfect and entered it in the county fair. It received a blue ribbon. My mother set the duck on our mantel. One day I got the idea to hollow it out and insert a small bottle holding my name and address and a dated message asking a finder to keep the bird but please write and say where the teal ended up. I went down to the river and let the current take it. When it floated off, it was as if my decoy came to life.

—What a waste.

—How far the thing might go, that’s what was important.

—How far did it go?

—Haven’t heard. But someday. Now you. Your turn.

She followed his gaze upward to the dolorous clown watching over them.

—My life—in my life—I don’t make wooden ducks. And if I did I wouldn’t toss them in a river. I make mental blueprints. Calculations. Then along comes some nullifying factor, and everything, my whole achievement, gets taken times zero.

—I know that equation.

The next night, Dominique, working to unwind in a warm bath, assessed him, and for the first time in months she thought perhaps it wasn’t too late for her to have a chance to summon the Dominique she believed she was destined to become and discover a new way to acknowledge her nature and learn to pursue a course instead of recourse. Silas might have means for disclosing different approaches before opportunities diminished and could no longer serve her. She stopped the notion cold: What am I thinking? The man carries a compass rather than a watch. Instead of ice, it’s a smooth rock to cool his whiskey. He looks at the sardines on his lunch plate and tries to picture them swimming the deep. Show him a bird egg, and he’ll see an egret.

Stepping out of the tub, she thought, Nevertheless, and to the mirror she whispered,

—Have to admit I like him. He’s not blind to my potential. And, he does know how to kiss.

To read more MIZZOU magazine stories online, visit mizzou.com.