Many Tigers have Mizzou history highlights memorized by the time they don a cap and gown: the birth of Homecoming, the story of MU’s iconic columns, a sports rivalry that lasted more than a century and the leaders who shaped the university into what it is today.

Take a trip to University Archives, and you’ll quickly realize how much more there is to Mizzou’s past.

“The university is an institution with a 175-year history,” says Michael Holland, director of University Archives and head archivist at MU since 1997. “While students may be here for only a few years, they are part of a larger and longer history.”

To document MU’s official functions and the Mizzou community, the archives accept a variety of materials, many of which come from departments when their records are no longer in use.

“The majority of what we have is on paper because that’s how business has been transacted since the founding of the university,” says Anselm Huelsbergen, technical services archivist. “We don’t just deal in paper. We’ll see audio recordings, video recordings, film. We also have some 3-D objects,” which include the first university seal, a uniform from the first football team and what is believed to be Walter Williams’ composition typewriter.

How do the archivists determine what to preserve?

“That’s sort of the art of the process,” Huelsbergen says. “We try to represent all the aspects of the university, all of its functions, all the individuals that take part in creating the history. Context is just as important as content for an archivist.”

They also pay attention to which materials are most often requested, which helps determine what to preserve for the future.

Records in the digital age

The entire collection takes up about 13,000 cubic feet of space. (For reference, that’s about 383,468 quarts of Buck’s Tiger Stripe ice cream.)

Some of the archives are housed in Lewis and Clark Halls, where the University Archives offices are, but most live in the records center on LeMone Industrial Boulevard.

"Currently, we’re still adding between 300 to 400 cubic feet of paper a year," Huelsbergen says.

That number is down from a peak of about 700 cubic feet of paper per year, due, in part, to an increase in electronic records, which pose new challenges for archivists.

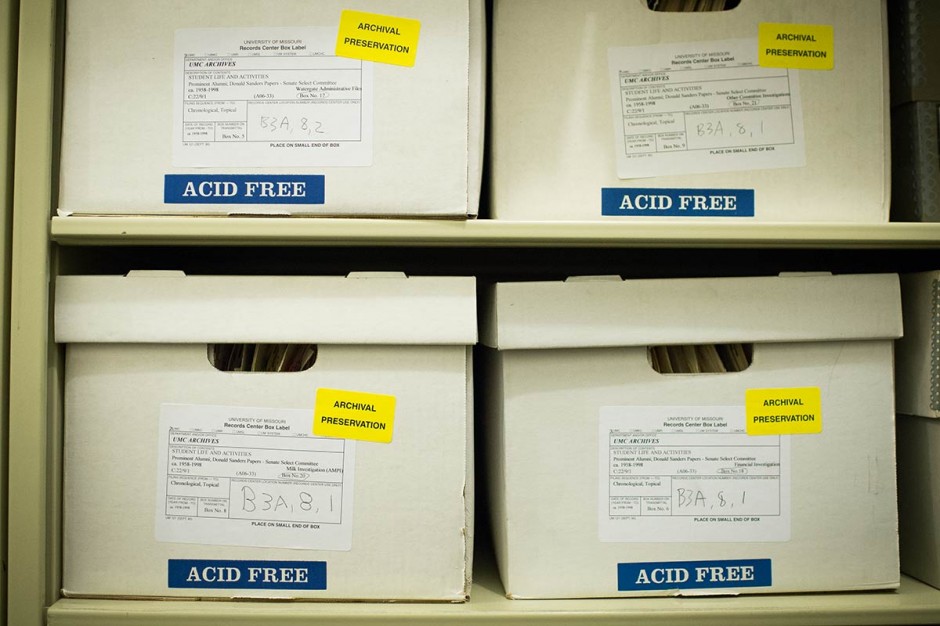

"When you take a piece of paper and house it in an acid-free folder and then in an acid-free container, your main concern is that something happens physically to that room," Huelsbergen says. "When you write some bits to a computer disc, you need to be sure that computer disc continues to spin, that you still have machines that can read it, that when they read it, they’re reproducing it accurately.”

Another disadvantage of electronic records is receiving materials.

"A lot of people give things to us because they have physical mass and don’t know what to do with them, or they’re running out of space," Holland says. "With electronic records, you don’t have that issue, so people don’t feel that imperative to move things out and send them someplace where they’ll be preserved."

Do your homework

Because the collection is so big, “you have to do your homework,” Holland says. “You have to know a little about what you’re researching before you show up.”

“In the world of archives, as opposed to libraries, we don’t have a cataloging approach where you control everything by access through author, title and subject,” Huelsbergen says. “Our concern is really where the materials come from, what office did they originate from and in what context were they created.”

Gary Cox, public services archivist, says the vertical files, or reference materials in the reading room in Lewis Hall related to broader topics (Homecoming, admissions, academic departments, student life, etc.), are a good place to start.

“Sometimes I’ll pull out a vertical file so they can get their secondary sources in line first,” Cox says. “You get your names and dates, and then it’s a lot easier to look through our finding aids.”

The finding aids, searchable on the archives website, are short descriptions of the materials in each collection.

Stranger than fiction

Requests for materials come from all over, Cox says.

“It really runs the gamut,” he says. “It can be administrators trying to understand how certain policies came about. It can be genealogists looking for information about an ancestor that was involved with the university. It could be sports fans.”

Many records requests are routine, but some can be pretty unusual.

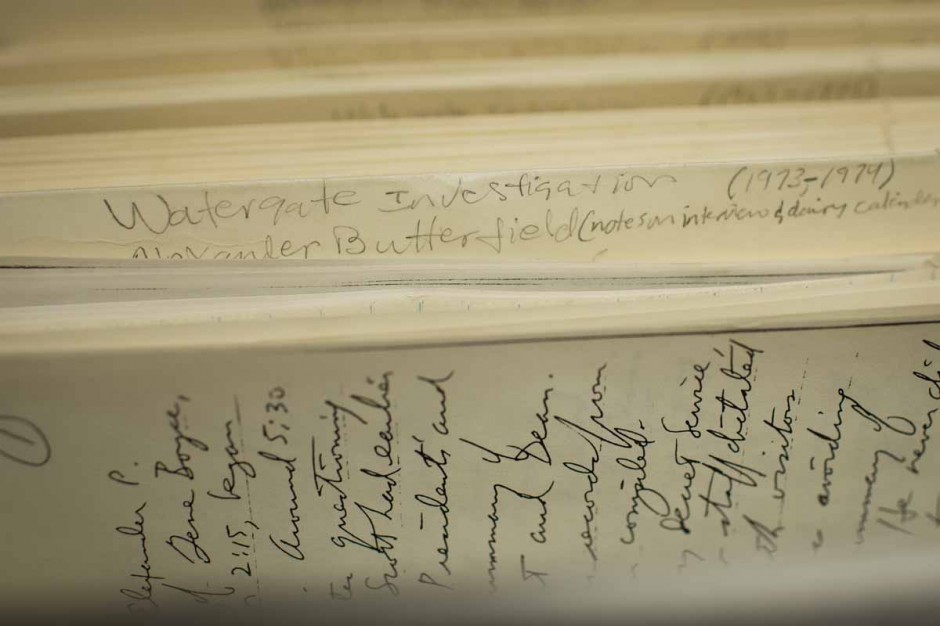

One group of records that sticks out to Cox is a scrapbook kept by Zoology Professor Winterton C. Curtis during the Scopes "Monkey" Trial in Dayton, Tenn., in 1925. Curtis was an expert witness by the defense but never got the chance to testify.

"While he was there for a week, he made a scrapbook of all the clippings and the weird broadsides," Cox says.

One of the stranger requests he receives is about Jim the Wonder Dog, a Llewellin Setter from Marshall, Mo., who lived from 1925 to 1937.

“He was supposed to be kind of a mind reader,” Cox says of the dog, who reportedly chose the winner of seven Kentucky Derbies, could understand commands in foreign languages and could predict the sex of unborn babies. “Supposedly he came to campus, and the veterinary professors did a test on him, and it was supposedly filmed. I’ve never found anything about that, but people always ask about him. It’s pretty strange.”

“That is the beauty of archival work,” Holland says. “It takes a very unimaginative person to get bored.”