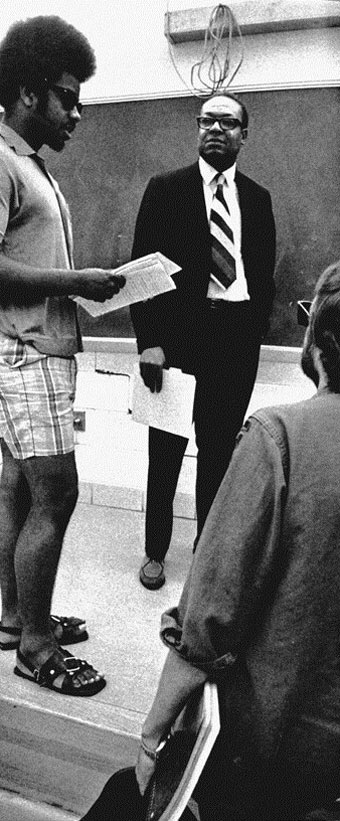

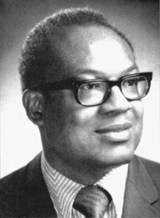

Arvarh E. Strickland, the University of Missouri’s first tenure-track black professor, an internationally acclaimed historian and a lifelong advocate for education, died Tuesday morning. He was 82.

Born in Hattiesburg, Miss., on July 6, 1930, Strickland earned a bachelor’s degree from Tougaloo (Miss.) College in 1951 and earned a master’s degree and a PhD from the University of Illinois in 1962. He taught at Chicago State College for seven years before being hired as the first black professor at MU in 1969.

But Strickland didn’t know he was going to be a trailblazer when hired by the history department. “I figured at such a large institution, there had to be another African American professor somewhere,” Strickland said.

Building black studies

Strickland was teaching one of the first black history courses in the state of Missouri outside of Lincoln University. His course, History 392: The Negro in Twentieth Century America, covered historic events from Reconstruction to the current period. The course aimed to help students reevaluate the place and role of black people in U.S. history.

Nearly 100 students enrolled, making it the second-highest enrollment of an upper-level history course on campus. Worried that students were enrolling for the novelty, Strickland warned them they would be in for an “unpleasant shock.” This was a history course, plain and simple.

Strickland led the way in creating a black studies minor at the university, and in 1971, MU made it official. Students in the College of Arts and Science could now graduate with a minor emphasis in black studies.

“The purpose of black studies is to give an understanding and appreciation of the black role in this country. It is not for ego gratification,” Strickland said. “The part blacks played in building up America is often dismissed, and there is little study of what blacks are doing today.”

Although black studies was initially only an undergraduate program, Strickland also worked with graduate students. He advised two master’s candidates through their theses in the first year. He was appointed by interim chancellor Herbert Schooling to aid in the recruitment of qualified faculty from minority groups starting in fall 1972.

“Even with the increased opportunities for black people to advance in our society, there is skepticism among young blacks,” Strickland said. “They have the typical Missourian show-me attitude. Show me I have something to aspire for.”

Professors who followed in Strickland's footsteps say his dedication to mentoring students is unparalleled. His record in guiding graduate students through the process of earning a doctorate far surpasses that of his colleagues and many reigning public intellectuals of the time, says Sundiata Cha-Jua, former director of black studies at MU. One of Strickland's major accomplishments as an educator was to give the world more educators.

“That’s his legacy,” says Cha-Jua, now a professor of history and African American studies at the University of Illinois. “Your task as a black scholar is to reproduce yourself and expand the pipeline, and Arvarh did that in the field of history at a higher level than most in his generation and many in subsequent generations, with fewer resources.”

Research and publications

In addition to his roles as an educator and mentor, Strickland was much involved with the research of history. He wrote the seminal History of the Chicago Urban League, published by the University of Illinois Press in 1966, and was the joint author of a secondary school textbook Building the United States.

Strickland was a contributing author to Encyclopedia Britannica in 1971 and was elected as a trustee of the State Historical Society in 1974. Later that year, his book five years in the making, The Black American Experience, was published. The publisher hailed it as “the most comprehensive program in black history available.”

In 2001 Strickland took the reference guide a step further with the publication of The African American Experience: An Historiographical and Bibliographical Guide, which he coauthored with fellow MU history professor Robert E. Weems. Weems says the experience helped him to both grow as a researcher and grow closer to Strickland.

“When we worked together on that project, I got the chance to see how meticulous he was as a scholar,” says Weems, who taught at MU from 1990 to 2011. “With collaborative projects, sometimes there's some friction involved, but I can honestly say we were better friends after that project than we were going into it.”

Advocacy

As Strickland continued to grow as a professor, he also evolved as an advocate for students. When the administration looked at various enrollment standards, Strickland was one of the leaders in supporting equal opportunity.

“I often get the idea, particularly with minority students, that we expect them to fail,” Strickland said. “Many who could succeed don’t because, as human nature, we live up to the expectation people have of us, especially those in authority. Many of us have been trying to change that image and feeling. I think in many ways, in some areas, we have been successful. But in a large place, it takes longer.”

In 1985, Strickland was one of seven councilors elected to the Phi Alpha Theta International Honor Society in History, and he later went on to become its international president. His leadership in the education of all students about minority issues, history and culture played a large role.

“He’s challenged non-minority students intellectually,” N. Gerald Barrier, then chairman of the history department, said. “Besides raising the normal issues, he’s forced them to look at their values and to look at aspects of the black experience as an American experience they may not have encountered.”

Honors

During the final years of his teaching career and soon after his retirement on Jan. 1, 1996, Strickland received several honors and awards. In 1994, he received the University of Missouri’s Byler Distinguished Professor Award and the St. Louis American’s Educator of the Year Award. In 1995, he was awarded the Alumni Association’s Distinguished Faculty Award and was placed in the Tougaloo College Alumni Hall of Fame.

In 1997 Strickland received an Alumni Achievement Award from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and distinguished service awards from the State Historical Society of Missouri and Phi Alpha Theta Honor Society in History. In 1999, he received the Carter G. Woodson Medal from the Association for the Study of African-American History and Culture.

“I would urge young people not to let barriers, real or imagined, keep them from preparing themselves to fulfill their dreams,” Strickland said when receiving the Alumni Association’s award. “And to not let anyone convince them that their dreams are unattainable.”

In 1998, the Missouri Endowed Chair and Professorship Program, with the support of the state’s legislature, created the Arvarh E. Strickland Distinguished Professorship in African-American History and Culture. Wilma King, the current chair of the Black Studies Program, is the current holder of the professorship. King says Strickland’s groundbreaking efforts to work with university administration in establishing black studies at Mizzou was tremendously important to higher education in the state.

“I’m very grateful. That has benefited me and will benefit other professors in the future,” she says. “That is a part of his legacy.”

In 2007, the General Classrooms Building was renamed Arvarh E. Strickland Hall at the urging of MU students in the Legion of Black Collegians; a room in Memorial Union also bears his name. Strickland taught on every floor of the former GCB during his 26-year tenure.

Deputy chancellor Mike Middleton was chair of the committee to choose the namesake. The choice of Strickland, a unanimous selection by the committee, was a “no-brainer,” Middleton says.

“He was such a significant man on this campus for so long that anybody else suggested paled in comparison,” Middleton says. “He was one of the most honorable men I knew. I can’t even think of any negatives; he was truly a good man.”

Middleton was a leading voice for MU students who demanded the university hire a black professor before Strickland was hired in 1969, and the two got to know each other soon after. They had intermittent correspondence while Middleton practiced law in Washington, D.C., and became closer friends after Middleton returned to teach at Mizzou in 1985. Middleton describes Strickland as a tall, dignified gentleman and a true academic with the mission to impart knowledge on young people.

Remembrance

Otto Steinhaus, Strickland’s former pastor at Missouri United Methodist Church, confirmed that Strickland died Tuesday morning. He is survived by Willie Pearl, his wife of more than 50 years, two sons and their families, and a great-granddaughter, Pearl.

“He loved history and was committed to excellence,” Middleton says. “But I suspect he’s probably most proud of his students and the influence he had on them over the years.”

Flags on campus will fly at half-staff through the weekend to honor the memory of Dr. Strickland. The Switzler bell will ring at 9:30 a.m. Saturday in conjunction with visitation, which will be held at Missouri United Methodist Church at 204 S. Ninth St. Services will take place at 11 a.m. Interment will follow at Memorial Park Cemetery at 1217 Business Loop 70 W in Columbia.