Oct. 13, 2022

Contact: Sara Diedrich, 573-882-3243, diedrichs@missouri.edu

When news broke earlier this year about the first-ever partial heart transplant that saved a two-week-old baby, reports didn’t include the deeper story — that the surgery was made possible by technology pioneered 20 years ago using pigs from the University of Missouri.

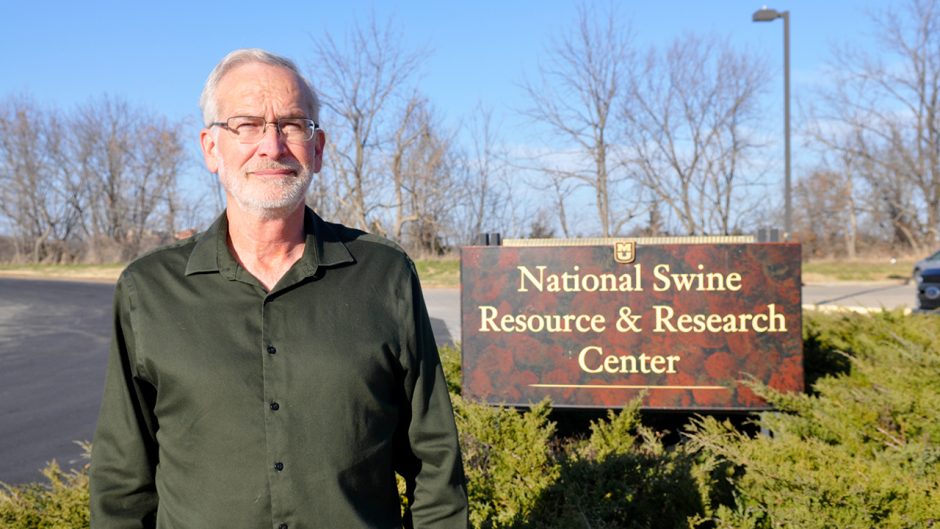

Randall Prather, a Curator Distinguished Professor and director of the National Swine Resource and Research Center (NSRRC) at MU, has been working behind the scenes for decades on genetically modifying pigs to prevent diseases that threaten both swine and humans. Recently, his research with pigs has been directly linked to successful transplants in humans — in January, surgeons successfully transplanted a pig heart into a human patient — offering hope to more than 100,000 people waiting for organ transplants.

Now add a six-month old — born with a congenital heart defect and today thriving with a partial heart transplant — to the list of patients who have benefitted from Prather’s breakthroughs. Still, the longtime researcher, whose work at MU began with cloning pigs, is modest about his lab’s impact on the field of transplantation.

“We made a small contribution in this case,” Prather said, adding more credit should go to Dr. Taufiek “Konrad” Rajab, a cardiothoracic surgeon and assistant professor in the College of Medicine at Medical University of South Carolina, who first proposed the idea of a partial heart transplant. “It’s very satisfying to see that what you’ve done has been a part of something much bigger," Prather added.

The idea

A year ago, Rajab contacted Kristin Whitworth at the NSRRC with his idea of using heart valves and the tissue around them for a partial heart transplant. If successful, such a surgery would especially benefit children whose heart valves aren’t working properly. But first, Rajab wanted to use pigs from the NSRRC to test his idea.

“One of the things that happens when you do a valve transplant is the valve generally doesn’t grow,” Rajab said. “So, if you do a valve transplant in an infant, you have to keep replacing the valves until the child stops growing. That means subjecting the child to repeated high-risk surgeries.”

Rajab and his team tested his partial transplant idea on three of Prather’s genetically modified pigs and in each case, the valve and surrounding tissue not only survived the surgery but continued to grow. In April, the fourth partial transplant in mammals — and the first-ever on a human — was conducted by surgeons at Duke University using a human donor. So far, it’s been a success, and the infant is reaching developmental milestones.

Rajab reached out to Prather’s lab via email to share his gratitude: “Thanks again for all your generous contributions to this project, it would not be possible without your help!”

The go-to source

This recent transplant success story is another example of how Prather’s longtime work with pig genetics has helped make MU the go-to source for genetically modified pigs used worldwide to push discoveries forward. The NSRRC at MU serves as a core National Institute of Health center for researchers from a variety of fields.

Years of study in Prather’s lab has helped create pigs that are now used to study a range of ailments, including cystic fibrosis, retinitis pigmentosa and cancer. Many other technologies have been developed as well, such as those to develop a heart and kidney that resists hyperacute rejection after transplant.

“What is so neat about the National Swine Resource and Research Center is the best researchers from all over the country come here to get their pigs,” Prather said. “We get to have a small piece of enjoyment from all the work they are doing.”