Published on Show Me Mizzou April 20, 2022

Story by Tony Rehagen, BA, BJ ’01

Jan Wesley remembers growing up in a quiet town in southern Pennsylvania with the distinct feeling that her mother had lived a secret, separate life. The mom Wesley knew was a prototypical 1950s housewife, the woman in charge of cooking and child-rearing and driving the family car to pick up Wesley’s father from the local newspaper when his reporting work was done. But, packed away in dusty cartons were magazines, portfolios and news clippings from another world — words written about and pictures taken by an intrepid wartime photographer who had packed her camera around the globe, a celebrity and artist who shared little more than a name and a vague resemblance with Wesley’s mother, Marie Hansen.

“There was a tremendous distance,” Wesley says. “It was a complete separation between this calm, domestic life and her work because it was all just in books. I never got more curious, never got further under the surface of what she did because I couldn’t see it or touch it or feel it. It wasn’t alive to me.”

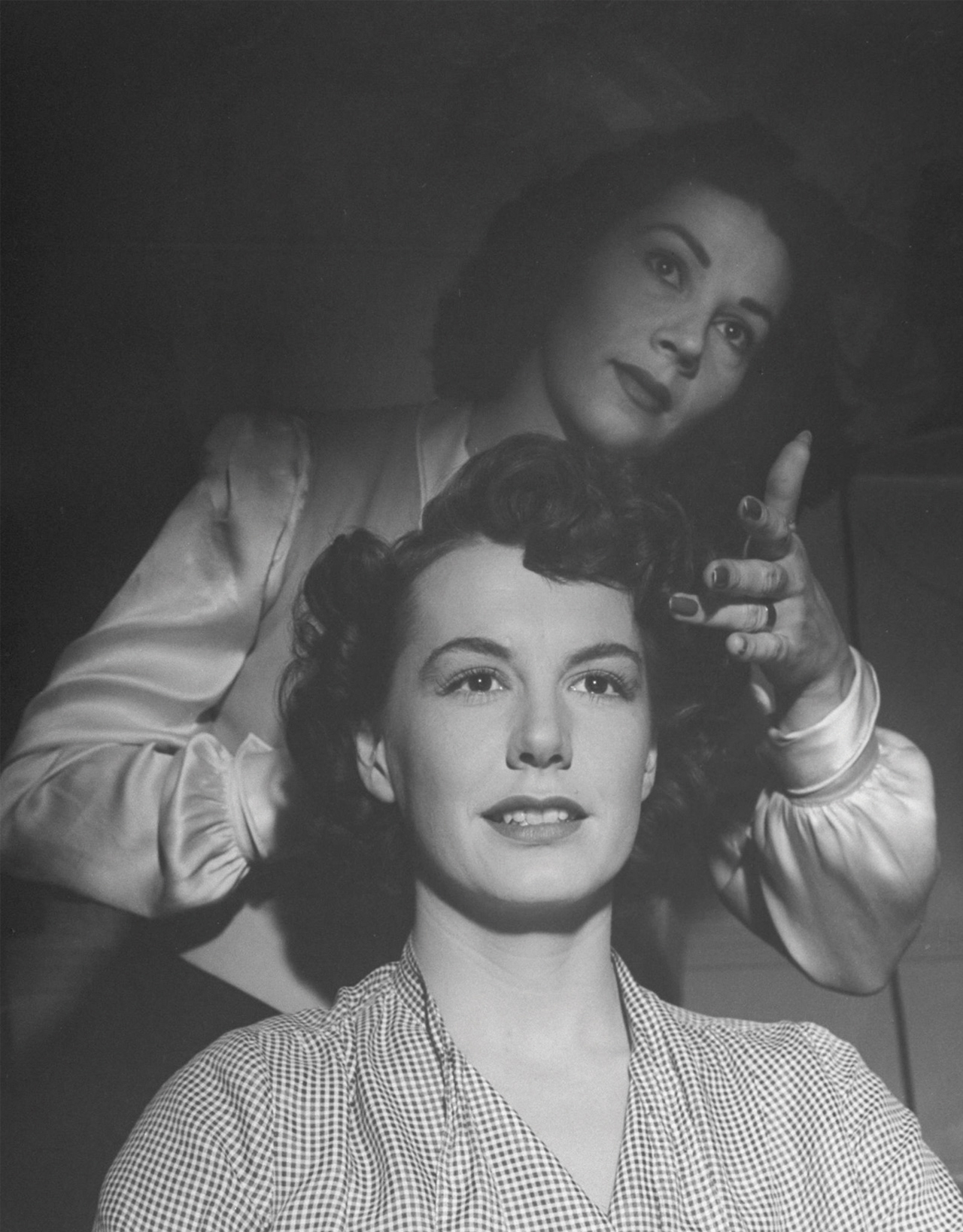

But Hansen had seen and experienced more by age 29 than any Midwest girl born in 1918 had any reason to expect. She had studied journalism at the University of Missouri and parlayed her skills as a reporter into a career in the burgeoning field of photojournalism. She had been only the third female staff photographer hired by Life magazine, a publication renowned for its breathtaking photography, at the height of its popularity. She captured images of U.S. presidents and movie stars and ordinary Americans on the home front during World War II. She had worked in Europe, Asia and South America and had been ahead of the times in covering early civil rights, the Cold War and even feminism. “She was a true pioneer of photojournalism,” says Rita Reed, professor emerita of photojournalism at the School of Journalism. “You can see as her work progressed that she was learning how to tell stories through multiple pictures, controlling things less and taking a more documentary approach. She was growing in that way.”

Then, abruptly, it all ended. The men came home from war and reclaimed their jobs and expected the women to return to the status quo, too. Hansen was left like so many women of postwar America: unwelcome in the wider professional world they had only begun to explore and yet too independent ever to fit comfortably back in the Barbie doll box they tried to put her in. And Wesley suspects it was her mother’s inability to reconcile these two lives that ultimately took the heaviest of tolls later in her life.

When Hansen first came to Mizzou in the late 1930s, the J-School had no photojournalism sequence. Instead, students who were interested in taking pictures toted cameras along with them on reporting assignments — they simply did it on their own. It was an initiative that Hansen took with her to her first job as a reporter at the Louisville (Kentucky) Courier-Journal in 1939. Within a year, she had been promoted to editor of the paper’s photo-heavy rotogravure insert. “When she got to the newspaper, she asked to be a photographer,” Reed says. “She persuaded them. That shows a determination and an interest in photography as a field that called to her, and she pursued it.”

Hansen pursued her passion for photojournalism to New York, where, in 1941, Life hired her as a researcher, one of many women working in the background of the publishing industry. But just as she did in Columbia and Louisville, Hansen pushed for a job as staff photographer, a request the editors granted a year later. The timing was not a coincidence. “She became a staff photographer in 1942 when men were being called up to fight in World War II,” says Alissa Schapiro, co-author of Life Magazine and the Power of Photography, who has studied Hansen and her fellow female photographers. “Women had access to male-dominated jobs. And this positioned her as an extraordinary female photographer in a male-dominated industry.”

Her assignments ran the gamut from hard news to entertainment and fashion to deeper cultural essays. She had photos that accompanied stories about the flooding of the Missouri River and the Truman Committee investigation of frivolous government spending. She produced a spread on how wartime wool rationing led to the outlawing of zoot suits, shots of actress Ava Gardner modeling a chiffon negligee on the set of one of her films and a portrait of Dwight D. Eisenhower. She was one of the first women to join the White House News Photographers Association and was one of only 11 photographers — and the only woman — able to keep up with Harry Truman on his famously brisk 2-mile morning walks. One of her first contributions was an essay on the new Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC), which included a picture of uniformed trainees seated on rows of bleachers, each wearing a gas mask — a haunting image that became an iconic depiction of war efforts on the home front.

In 1944, Hansen married David Wesley Nussbaum, a reporter for Life, but she kept Hansen as her professional name. Even though she was at the apex of the industry contributing award-winning photography, even though she was invited back to MU to judge the prestigious Pictures of the Year contest, Hansen was constantly reminded that she was a woman in a man’s world. For instance, in the front of the issue of Life containing her WAAC package, the editors ran a behind-the-scenes photo of Hansen at work, looking into the viewfinder of a camera on a tripod. In the background is a male Army officer leaning over to get a look at Hansen. The caption reads: “Pretty, 24-year-old Marie Hansen, one of the newest members of Life’s photographic staff, makes her first big splurge this week with the essay on the WAACs … .”

“It’s the way a lot of these photographers were contextualized,” Schapiro says. “It’s an interesting push and pull that gets into the relationship between her photos of these women within its larger social dynamic of gender: Women are still pretty and do feminine jobs for the war effort. They are helping out, but it’s not making them masculine, and it’s temporary.”

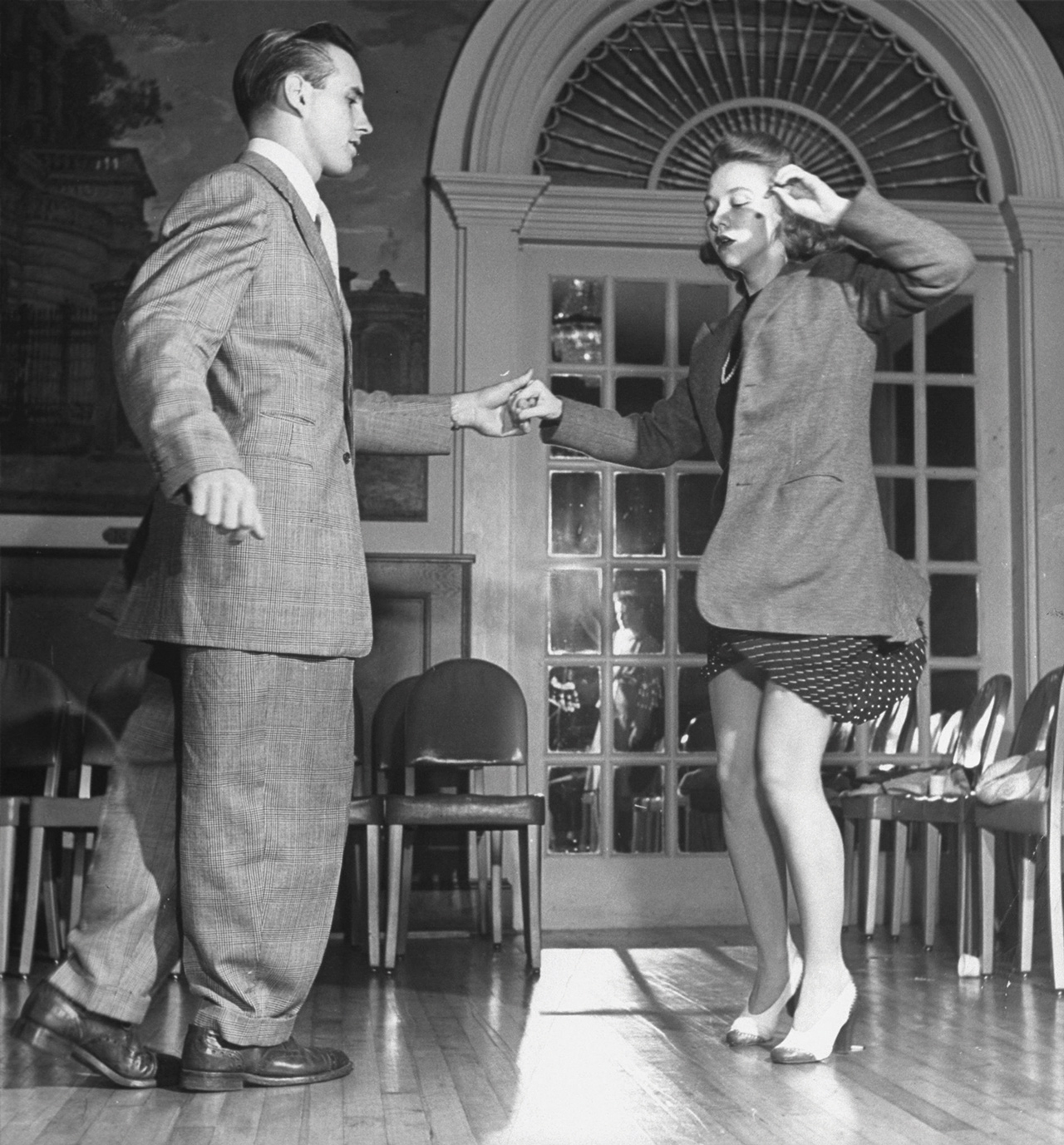

For Hansen, it was temporary. In 1947, the war over and the men back home, she left her staff position at Life, when David, who had also quit the magazine, received a grant from Holiday magazine to freelance all over the world. Together, they did stories on Picasso, Hitler’s yacht, the king of Spain and street life in Paris. They traveled the globe for a year until Hansen became pregnant with Wesley. When they returned to New York, they decided to leave the city to raise their family. By 1950, the year Wesley was born, the family was in York, Pennsylvania, where David worked as a newspaper reporter. Hansen shot some photographs and edited copy for some companies, worked with the local League of Women Voters, volunteered at polling places on Election Day, all while keeping house, tending her prized flower garden of roses and azaleas, and rearing their daughter.

Wesley says that her mother never worked as a photographer again. Eventually, she sold her equipment to help with living expenses. “What was she going to do?” Wesley says. “Get a photo studio and take pictures of kids for school?”

Hansen rarely spoke of those wartime and postwar adventures — that was a pastime reserved for Wesley’s father, who is the one who kept and stored all of Hansen’s clippings and mementos from her professional life. Occasionally, he’d tell house guests stories about Hansen’s work, which, Wesley remembers, made her mother smile.

But as the years went on, happiness was something that Hansen struggled to find and hold on to. Instead, she became clinically depressed and turned to alcohol, a worsening habit that greatly frustrated her husband. “There was a lot of arguing,” Wesley says. “I’d be the peacekeeper. I was the adult child of the alcoholic, taking care of her until I left for college.” Things got so bad that Wesley remembers living in dread of the phone call that would inform her of her mother’s death. It came in 1969 when Hansen died by suicide at age 51.

Today, Wesley is proud of her mother’s legacy. She thinks it’s important to remember Hansen’s contributions to photojournalism in those early years of the discipline. But, of course, it’s also vital to remember her struggles as a woman in a man’s world. “It’s hard going through those materials again and not have the stab be a little more powerful than the joy. But it is.”