Published on Show Me Mizzou Dec. 17, 2021

Story by David LaGesse, BJ ’79

A walk inside the new Roy Blunt NextGen Precision Health building reveals hallways packed with clinics, offices and labs — all designed to break down walls that have separated health care research and practice. “Everything is under one roof in this building,” says Richard Barohn, executive vice chancellor for health affairs and executive director of NextGen Precision Health. “It’ll have a lot of opportunities for what I call ‘collision time.’ ” Happy collisions, that is, leading to new ideas and unusual partnerships. Links that can bridge the gap between research in a lab and care in a clinic.

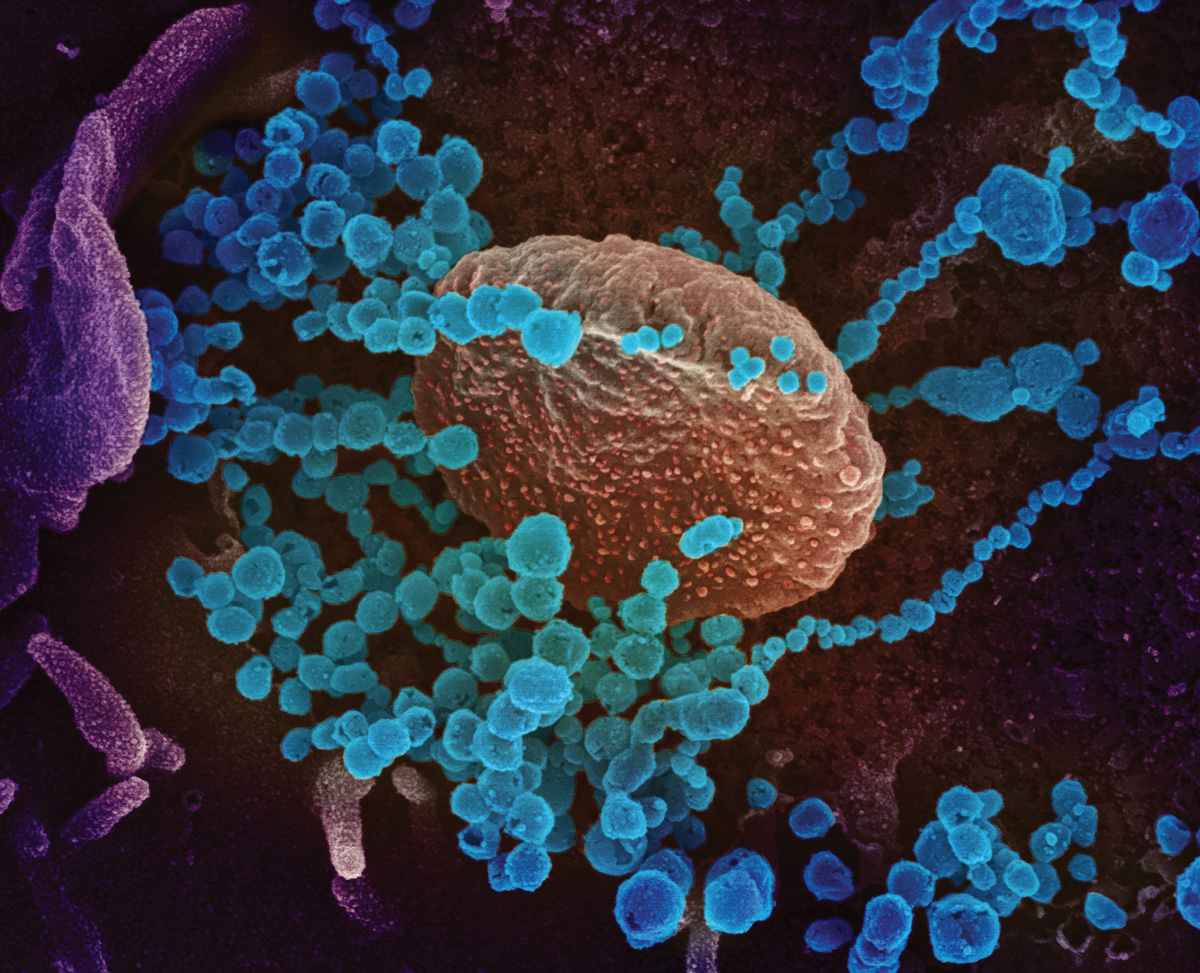

The $221 million building’s large size is telling, as well. It needed room for cutting-edge technology, including a combination that’s perhaps unique to the country: the best in magnetic resonance for peering into organs and the best in electronic microscopes for peering into individual cells. The building needed room for engineers developing new devices and for veterinarians conducting clinical trials of drugs and therapies that might later cure humans.

And the added room means bigger studies, says Elizabeth Parks, professor of nutrition and exercise physiology. “We want more people in our studies,” she says. “You learn more about how they differ and how you might be able to treat them as individuals.”

A bit counterintuitive is that precision health — the right cure for the right person at the right time — requires the study of multitudes. To that end, NextGen also incorporates big data, including a joint MU and University of Missouri–Kansas City operation that’s expert in ferreting out hidden patterns in human illness. Other investigators focus on what influences the health of whole populations, including ethnic groups, geographic areas, ages or genders.

The pandemic has driven medical advances at what appears to be warp speed, an efficiency arising from decades of research. In that sense, COVID-19 has only reinforced the urgency behind NextGen, says University of Missouri President Mun Choi: “We’ve all seen how our future depends on the medical innovations happening right here, right now.”

Tackling the big three

With its world-class building and technology, NextGen has helped draw top-tier medical investigators to MU, who, in turn, have shaped its areas of research. The initiative started with the three biggest human killers: cancer, neurological disorders and cardiovascular disease. Then came key hires that elevated two other areas, infectious disease and reproductive health. “It’s really about the talent,” Barohn says. “You need the infrastructure and the equipment, but it’s the people who will make MU a world leader in precision health.”

Gathering top researchers

The NextGen initiative draws together centers and researchers from across Mizzou and the University of Missouri System’s other three universities. For example, Russ Waitman is a joint appointment between MU and the University of Missouri–Kansas City who came to lead the NextGen Data Science and Analytics Innovation Center. “He’s sort of a genius at extracting nuggets of knowledge from medical data,” Barohn says. Also under development is the NextGen Center of Excellence for Influenza Research at a site south of Mizzou’s campus, where investigators can safely study dangerous pathogens under the direction of Xiu-Feng “Henry” Wan, also a newcomer. MU’s flu research already has attracted $15 million in federal research funding.

Moving from lab to clinic

The College of Veterinary Medicine offers special assets for NextGen, including its own imaging center that rivals those in many medical centers for humans. The school’s Veterinary Health Center, which provides Missourians with checkups, preventive health care, and specialized treatment for companion animals and livestock, also offers clinical trials of potential breakthroughs. “Our role is the translational piece,” says Carolyn Henry, dean of the college. “We help with taking research through trials to produce a test or treatment for any species affected by a disease, be it dog or human.”

Seeing the next step

The NextGen building houses powerful imaging capability. Few, if any, facilities nationwide can boast of the combined magnetic resonance imaging and electron microscopy that resides in NextGen: a 7T MRI, which can image internal organs in fine detail, and as well as Krios G4 and Spectra 300 electron microscopes, which can see into cells and even atoms. “These machines put us at the leading edge,” says Talissa Altes, professor and chair of radiology in the School of Medicine. “We’ll also be developing new ways of using the technology.” Working with MU to tweak the gear’s performance are manufacturers Siemens Healthineers and Thermo Fisher Scientific, which expanded NextGen’s capability with in-kind donations.

Partnering with government

When the pandemic hit and budgets crashed, Mizzou had a hole in the ground where NextGen was under construction. Would it get built, and when? “I was a little worried,” says Dustin Schnieders, the university system’s director of government relations. But the state’s commitment didn’t waver, and it remains crucial to the initiative’s future. The legislature and governor later converted Missouri’s $10 million investment to an annual allocation for NextGen operations in the university’s core funding, which means it should continue every year.

Growing missouri’s economy

The NextGen initiative is expected to offer significant return on its investment, according to a study by the university system’s Economic and Policy Analysis Research Center. The initiative will not only improve Missouri health care but also generate $5.6 billion in economic activity through 2045, according to center researchers. The state’s general fund alone could see a bump of $227 million in tax revenue.

Conducting key trials

Opening in the spring, a section of the NextGen building targets the key goal of translating basic research into real-world treatments. The Clinical Translational Science Unit will provide the space, staff and equipment to conduct innovative clinical trials in humans. The unit builds on similar but smaller facilities at MU, substantially expanding capacity for testing drugs, devices and lifestyle treatments, says Parks, the professor of nutrition and exercise physiology. “Conducting basic and human research under one roof is a huge advantage,” she adds. “Our discoveries can immediately help patients.”

Sharing health statewide

In a groundbreaking approach, NextGen will spread its benefits across all Missouri counties and cities by working through MU Extension. Outstate residents already know extension’s work in agriculture, business and health education. Now it becomes a two-way pipeline for medical research — informing NextGen of rural residents’ health challenges and enabling them to participate in the initiative’s trials of new treatments. “I don’t know of anywhere else in the country that’s done something like this,” says Marshall Stewart, MU’s vice chancellor for extension and engagement. Extension will partner with communities, building on video-conferencing education already offered to physicians at the service’s far-flung locations statewide.

Combining therapy and diagnostics

Theranostics is a relatively new field in medicine, combining therapy with diagnostics. That’s the magic of new, radioactive drugs that can better identify cancer tumors or treat them or both. Newly recruited to Mizzou as part of the NextGen initiative, Carolyn Anderson leads a lab that leverages its across-the-street proximity to MU’s Research Reactor, a leading producer of radionuclides used in pharmaceuticals. “We really are at the forefront of theranostics research,” Anderson says, “having access to new radionuclides and new production technologies before they are disseminated to the rest of the country.”

Fixing disparities

Perhaps no field demands more teamwork than population health, in which researchers cooperate to identify health disparities faced by groups, defined perhaps by ethnicity, location or gender. “We’ll be looking at these populations and how we can improve treatments for them,” says Gillian Bartlett-Esquilant, a new associate dean at the School of Medicine who helped develop a new doctoral program that includes an emphasis area in precision and population health. NextGen’s emphasis on collaboration and its linked data sets promise to help bridge gaps among researchers as they seek out and treat health disparities among Missouri residents, where some populations suffer higher rates of illnesses, including cancer and heart disease.

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.