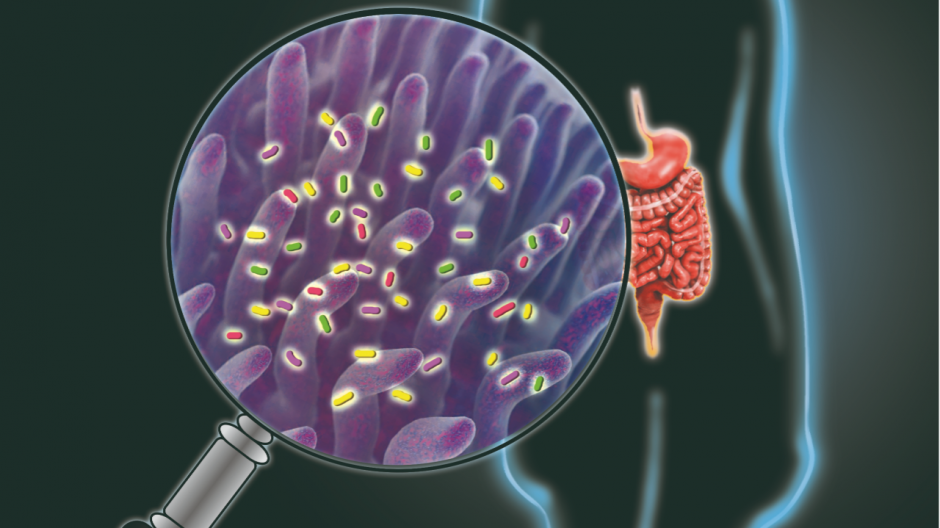

An illustration of the non-invasive way for identifying the major functions of the gastrointestinal tract. Illustration is courtesy of Marina Resnyanskaya.

Feb. 3, 2021

Contact: Eric Stann, 573-882-3346, StannE@missouri.edu

A healthy person has a general balance of good and bad bacteria. But that balance is thrown off when someone gets sick. So, to help boost their levels of good bacteria, many people take probiotic supplements — live bacteria inside of a pill. Various commercial probiotic supplements are available for consumer purchase, and while health experts generally agree about their overall safety, controversy surrounds their efficacy.

Inside the human body lives a large microscopic community called the microbiome, where trillions of bacteria engage in a constant "tug of war" to maintain optimal levels of good and bad bacteria. Most of this struggle takes place within the body’s gastrointestinal tract, as bacteria help with digesting food and support the immune system. Although health experts believe good "gut" health is key to a person’s health and well-being, scientists are still developing a detailed picture of what goes on inside a person’s gastrointestinal tract.

“Until now, we have not had any ways to noninvasively monitor activity in the intact gastrointestinal tract, given the unique chemical environment, variable distribution and highly dynamic nature of the gut microbiota,” said Elena Goun, an associate professor in the Department of Chemistry at the University of Missouri.

In a new study published in Science Advances, Goun and an international team of scientists have developed a noninvasive diagnostic imaging tool to measure the levels of a naturally occurring enzyme — bile salt hydrolase — inside the body’s entire gastrointestinal tract. Goun said their tool accomplishes three major functions:

- Predicts the clinical status of inflammatory bowel disease, such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

- Determines the efficacy of many commercially available probiotic supplements by testing for the level of bile salt hydrolase, which is responsible for all of the major health-promoting functions of probiotics.

- Evaluates whether certain types of prebiotics — dietary fibers known to support digestive health — can increase bile salt hydrolase levels in a similar way that probiotic supplements do.

Goun, who specializes in the development of biomedical imaging tools to advance the knowledge and understanding of various processes underlying human diseases, believes their findings are exciting, especially with the discovery related to prebiotics, which can be naturally found in foods such as whole grains, nuts and seeds, and fruits and vegetables.

“Prebiotics are often used in combination with probiotics to enhance their functions in the body,” Goun said. “We show for the first time that certain types of prebiotics alone are capable of increasing bile salt-hydrolase activity of the gut microbiota, which among other health benefits has been shown to decrease inflammation, reduce blood cholesterol levels, and protect against colon cancer and urinary tract infections. In my opinion, this discovery is huge because the production and storage of prebiotics is less expensive than with probiotics.”

Previous reports have noted high bile salt-hydrolase activity of the gastrointestinal tract is reflective of better digestive health and a lack of inflammation in the body. Goun said their noninvasive method uses bioluminescence — a chemical reaction that produces light inside a living organism — to measure the level of bile salt-hydrolase activity throughout the entire gastrointestinal tract.

“Our imaging tool is a bioluminescent probe in the form of a capsule,” Goun said. “When someone swallows it, it’s exposed to the intact gut microbiota while traveling throughout the harsh environment of a person’s entire gastrointestinal tract. After it passes out of the body, we can analyze a person’s stool sample. We can take the results from that analysis and correlate it with the amount of bile salt-hydrolase activity within the human gastrointestinal tract.”

Goun believes this research could lead to better precision medicine treatments by providing a way for scientists to better understand how a person’s individual gut health is connected to various human pathologies, or the origin and nature of human diseases.

“This is the first example of the use of bioluminescent imaging probes in humans,” Goun said. “The gut microbiome plays a huge role in various health issues such as cancer, diabetes, obesity, Parkinson’s disease, depression and autism, and now, this new tool will help us better understand the relationship between the gut function and these diseases. In addition, it will allow us to develop more effective probiotics and prebiotics to improve gut health.”

Highlighting the promise of personalized health care and the impact of large-scale interdisciplinary collaboration, the University of Missouri System’s NextGen Precision Health initiative is bringing together innovators from across the system’s four research universities in pursuit of life-changing precision health advancements. It’s a collaborative effort to leverage the strengths of Mizzou and entire UM System toward a better future for Missouri’s health. An important part of the initiative is the construction of the new NextGen Precision Health building, which will expand collaboration between researchers, clinicians and industry leaders in a state-of-the-art research facility.

“Noninvasive imaging and quantification of bile salt hydrolase activity: from bacteria to humans,” was published in Science Advances. This was a highly collaborative work, including institutions such as the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne, Switzerland; Nestlé Institute of Health Sciences in Lausanne, Switzerland; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; and Nationwide Children's Hospital in Columbus, Ohio.