Published on Show Me Mizzou August 19, 2021

Story by Tony Rehagen, BA, BJ ’01

Photos by Nicholas Benner

As the son of two voracious readers, growing up in a farmhouse in the eastern Missouri Ozarks surrounded by books, Steve Wiegenstein knew he was born to be a fiction writer. He just had to wait a few decades while life happened.

A retired college professor and administrator, Wiegenstein, BJ ’76, MA ’82, PhD ’87, didn’t publish his first novel until he was 56. But he has since more than made up for lost time, putting out two more novels and a book of short stories in the past eight years. The latter work, Scattered Lights, set in Wiegenstein’s native Ozarks, thrust the 66-year-old author into the international spotlight when it was named as a finalist for the 2021 PEN/Faulkner Award. Previous finalists have included American literary legends like Larry McMurtry, Joyce Carol Oates and Jonathan Franzen.

But if Wiegenstein’s circuitous route to this moment has taught him anything, it’s not to get too wrapped up in chasing accolades but rather to focus on the task at hand. After all, much of writing, particularly fiction, is about the author achieving proper perspective on the story and the characters therein — to let events unfold organically. “I think things happen when they are due to happen,” Wiegenstein says. “It’s wonderful to get the recognition. But I don’t begrudge the time spent building my career. There’s a whole life there.”

That life began in Annapolis, Missouri, a tiny farming town in Iron County, near the Black River. Wiegenstein’s parents were farmers who supplemented their livelihoods. His father was a quarry supervisor, his mother a freelance journalist and copywriter. Both loved to read, but Wiegenstein distinctly remembers his mother clacking out newspaper articles and ad copy on her typewriter at the dining room table. He idolized her.

The son tried his own hand at writing in high school and as an undergraduate at Mizzou, but he was only good enough to know he wasn’t good enough. It wasn’t until Wiegenstein got to graduate school at MU, after a stint as a reporter for the Wayne County (Mo.) Journal Banner, that he started believing in his compositions and publishing the occasional story in literary magazines. “It’s only after I’d been out of school for a few years that I developed the kind of discipline and objectivity about my work that allowed me to step up my ability,” he says. “I had a more mature outlook and a better sense of what I wanted to say.”

Even so, writing fiction was still more or less a hobby while he built a career in academia. Finally, in 2012, Wiegenstein acted on an idea he’d been saving for nearly 30 years. For his setting, the journeyman professor returned to his roots. Slant of Light was the first novel in the trilogy about Daybreak, a utopian settlement in the Missouri Ozarks founded before the Civil War. Its residents came of age during the rapid changes of the late 1800s and early 1900s. “I look for settings that have personal meaning for me,” he says. “I gravitate to rural people and Ozarks people in particular because that’s where I’m from, and they are what I know.”

Scattered Lights, which brought overnight attention to Wiegenstein’s work, puts the author’s examination of those people into the 21st century. These characters are virtuous but imperfect, just trying to make their own way. There’s Miss Elizabeth, a widow who quietly ruffles feathers among her small town’s elite by refusing to take her place among them. Charley Blankenship is a black sheep ex-con who, despite his son’s denouncement of him, breaks the law again in a vain attempt to secure the child’s future. And the collection is bookended by sketches of Larry, who at first blush appears to be a Bible-thumping country zealot but who comes to question his core beliefs when life isn’t working out as he had prayed it would. “What I greatly admire about Steve’s work is that he steers clear of stereotypes,” says award-winning novelist Ann Weisgarber. “He writes with compassion. At the same time, his characters are rich with flaws. That makes for stellar fiction.”

Although it didn’t quite make for PEN/Faulkner Award-winning fiction (the honor went to Deesha Philyaw, also a National Book Award finalist), Wiegenstein is taking his sudden success with the evenhandedness one would expect from a lifelong academic living out his dream in retirement. He’s working on the fourth installment of his Daybreak series, pushing on without regret. “Now I feel free to work on creative writing and do it from a perspective where I feel seasoned to do it as well as I can,” he says. “And I don’t concern myself with the fact that I didn’t do it earlier. There’s still plenty of time.”

Read an essay he wrote about life and floating for MIZZOU magazine below.

Same river twice

For a writer who grew up on a southern Missouri farm, what better teacher could there be than the state’s rivers and streams. During a lifetime of float trips, Steve Wiegenstein has come to cherish the beauty of those sanctuaries. He’s spent a career pondering the questions they’ve posed on matters of birth, death, and the struggle and wonder of life’s passages in between.

Essay by Steve Wiegenstein, BJ ’76, MA ’82, PhD ’87, PEN/Faulkner finalist, 2021

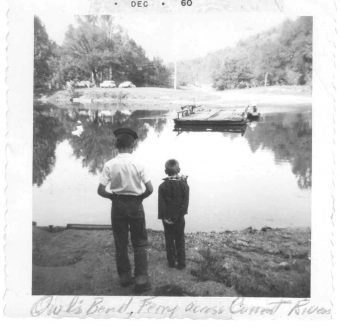

The best way to experience a Missouri river is from its surface, under your own power. Traveling by any other means makes you a mere observer. My first float took place on a salvaged johnboat my dad picked up somewhere, patched with rivets and caulk, and hauled in the pickup a few miles up the Black River, near our farm in Reynolds County. The farm’s previous owner had been a tie-rafter during the Depression, muscling mile-long assemblages of rough-hewn crossties downriver to the railhead at Clearwater. He had left behind a big steering oar, so we used that in the stern and scavenged a canoe paddle from a root wad for the bow. They worked fine for the johnboat, which didn’t need a lot of steering, as it could bounce from obstacle to obstacle and scrape over low spots without much help. From there we floated to the Highway K bridge, where the tractor and wagon had been parked for the return home. Now, 50-plus years later, I make the same float in a hard plastic kayak, and the outfitter’s bus is driven by the grandchildren of those who were once our neighbors and classmates.

Thus began a lifetime of floating — streaming along on “a living thing, a third friend,” as Ward Dorrance put it in his 1937 book Three Ozark Streams. He wrote that a day seeing a stream “speeding out of its mist at dawn cannot be like another day,” words that have rung true in my own experience again and again. Setting out into an Ozark stream is a small rebirth, a revisiting of that old metaphor about the river of life. Heraclitus had it right 2,500 years ago: One never steps into the same river twice — a musing on change that’s as much about people as water. I’ve been riding rivers since I was a kid, and they had a multitude of names: St. Francis, Black, Current, Jacks Fork, Eleven Point and more. Missouri, the state of rivers, the state named after a river.

What is this state of ours if not a place where you find an open craft and push out into the current? Mark Twain knew this, and for all the complicated legacy of Huckleberry Finn, we are left with two friends afloat at night, making stories out of the stars. John Neihardt, the university’s poet-in-residence for many years, knew this, claiming the Missouri as the symbol of his own soul in his 1927 The River and I. So whenever a Missourian with literary ambitions steps from a bank onto a stream, there’s a parade of predecessors to salute and emulate. When I began work on my first published novel, I sought a setting, and looking into the deepest, most treasured corners of my heart, as one does on such a task, I saw a mist-shrouded Ozark valley with a running river on one side and a steep hill on the other. My novels all take place in a riverside village in the Ozarks, a fictional spot, though if you think of Galena, Eminence or Van Buren, you’ll get the idea. The inhabitants depend on the river, they fight it, and sometimes they die in it. In my short-story collection, Scattered Lights, there’s a glimpse of what this 19th-century village has become: a summer camp whose owners make the kids swim in the camp’s lifeguarded pool instead of risking the liability-filled waters of the nearby river.

If Missouri is a state known by its rivers, then a river journey is the way to know a Missourian. Every Ozark stream has its champions. The Niangua, angler-friendly and placid, with spectator cows watching from the banks. The North Fork, remote and wild. The Elk, with its dramatic overhanging bluffs, and the Gasconade, with its mile-high ones. But it’s the Current that always shows up on the tourist brochures, and for good reason. It slices southeast through the midsection of the plateau from Montauk to Doniphan and beyond, queenly and photogenic, great springs lining its path. So we pack a dry bag, point the car in that direction and embark.

First Shoal: Disruption

In the summers before I left my Reynolds County home for the university, I worked as a counselor at a children’s camp, supervising timid city kids as they swam, shot .22-caliber rifles and rode horses. Group after group of campers floated the same stretch of river dozens of times, with an overnight campout as the pinnacle of their stay. Our vessels were 12-foot aluminum canoes, rackety and almost indestructible, and although the kids received daily practice at the quiet hole of water across from the camp, their reaction upon reaching the first mild S-turn after launch was unreasoning terror. Something was pushing them in an undesired direction, and all their mad paddling had little effect.

Their response was usually to paddle harder, often with the kid in the bow paddling in the opposite direction to the kid in the stern, canceling each other’s effort. The canoes bounced off trees; the campers shouted recriminations at one another; and the counselor in the lead waited in the still water below as the canoes floated down with their lifejacket-clad cargoes, sideways and backward, occasionally with someone in tears. The first lesson of a float trip is that the world has force beyond your abilities to manage. Flail or adapt.

For most of human history, rivers were highways. In my novel Slant of Light, James Turner arrives at his settlement by flatboat up the St. Francis from Arkansas, a fictional journey that is plausible enough. If steamboats could navigate the Osage all the way to Osceola, why not a flatboat up the St. Francis? Railroads supplanted waterways for commercial traffic after the Civil War, leaving the rivers to the locals and the occasional adventurer from outside. In their rich book James Fork of the White, the photographer-writer team Leland and Crystal Payton describe how float trips transformed from rugged sportsmen’s outings to relaxed, four- or five-day affairs aimed at the leisure class, spurred by railroad brochures from the Missouri Pacific. And even in the 1950s, when Leonard Hall, the great popularizer of the Current River, pretty much brought about the creation of the Ozark National Scenic Riverways, floating was still largely a genteel angler’s pursuit. His trips down the river are like those old-time travels, with a guide floating ahead to set up camp, cook dinner and prepare the toddies while Leonard and Ginny fish their way along. In Hall’s day, the Current was a big, beautiful, unregulated river that needed protection not just from the Corps of Engineers’ dam mania but also from the locals, who didn’t treat it with sufficient reverence. They ran cattle along its banks and plowed its bottomland. They engaged in environmentally problematic practices like open range and the annual burning of the forest floor. All in all, Hall was right, but the federal government’s acquisition of the scenic riverways land left resentments that still ache.

Many of my fellow camp counselors were MU students, so I arrived in Columbia in 1973 with an unrealistic vision of its glories, expecting both the Library of Alexandria and Kubla Khan’s pleasure dome. It’s no surprise, then, that my undergraduate years resembled the experience of those camp kids, with a lot of wild effort in dumb directions and striving after goals that I had no business attempting. But eventually, you learn to navigate, to sense and anticipate the forces that are driving you in a particular direction, forces that cannot be overpowered but can be used to accelerate toward the desired end. Once the nose of the boat reaches safe water, the rest of the craft will usually follow.

Eddies and Springs

But whatever their level of luxury, whether they arrive at the Current River with a kayak strapped to the roof or roar up from Van Buren in a custom motorboat, I can’t kick too much about floaters of any sort, for they are on their own versions of the same quest — the search for something outside themselves, something authentic and natural. I avoid the weekenders because their version of nature differs so radically from mine, but I sense a kinship. Like me, they want to step out for a little while, to thrust a hand into the water where a spring branch comes in and feel the raw chill, to pick up rocks from the gravel bar and skip or kerplunk them back into the stream.

My family divides the world into two kinds of people — the ones who adapt to the float’s slow pace and simplicity versus the ones who talk incessantly and paddle as if they have an appointment to keep. For us, the question, “Can they go on a float?” has taken on almost moral dimensions, implying a certain attitude, an openness to experience and a willingness to go with the flow in the most literal sense. When I brought my future wife home to the farm for the first time, she eagerly stepped into the canoe and fell into the river’s serene rhythms, pretty much sealing the deal.

We were graduate students in MU’s English department then. One year, we helped organize an ill-fated float with our fellow scholars that taught us not everyone is suited for a river trip. An overambitious itinerary, a group of novices and a steady downpour tested us all. Some relationships managed to find sweet water despite the obstacles; some dragged on the rocks and some got swamped.

But for those who feel the pull of the river, the rewards surpass calculation. The feeling of an alternate way of measuring time and space leads thoughts toward the mystical. Prosaic old Schoolcraft only recommended the Current River to “the planter and speculator,” but the rest of us see the sacred. Ward Dorrance, slicing through predawn mist into a deep hole, with sunlight filtered through sycamores and cardinals singing overhead, felt the urge to fall to his knees, and he wasn’t wrong. When I think of human-created holy places, I think of the vaults of cathedrals and capitol domes, their oversized scale inspiring awe, and the same is true of many natural places we call sacred, our Half Domes and Grand Canyons. But the wonders of a float trip are fleeting, caught out of the corner of an eye.

The stillness of a fish resting in the still water below a boulder, the imperturbable gaze of an eagle from the top of a shortleaf pine, the bobbing of a submerged tree branch according to its own mysterious physics: A float trip is a compendium of little miracles for those who have eyes to see. And it’s a lesson that miracles don’t need to be grandiose to be profound. Perhaps the greatest gift of the river is how it opens a place for silence, such a rare commodity today, and one that is needed most by those who do not even notice its absence. The trip begins with chatter and conversation, but those everyday topics gradually fall away. We drift for miles without speaking, or speaking only of necessary things, a barely visible rock ahead, an uncertain fork, an animal on the bank. Then, like the dome of water that rises when you pass over a riverbed spring, the silence breaches and another kind of essential subject bubbles up: memories, insights, aspirations, deep thoughts for deep water.

And the springs! Is it any wonder that the ancients built temples beside them? But no temples flank Ozarks streams, just hydrologists’ carefully crafted posters that tell us of the geology below. Water migrates through the limestone under every hill, shaping the landscape. Streams disappear in one county and gush out at the base of a bluff 20 miles away. But when I gaze into the mesmerizing depths of Blue Spring, or stand above the massive outflow of Big Spring, or take the long walk down to Greer Spring to see its mossy tumble, I lose track of science. I drop into the elemental mystery of water springing from rock, creation seemingly from nothing. Over the years, I’ve been invited to several river baptisms, and though my own religious tradition doesn’t require full-body immersion, I understand the impulse. If I should ever be baptized again, I’d want it to be in the cleansing waters of an Ozark stream. I already experience a spiritual regeneration every time I push out from the shore.

But alongside this pleasure is the pleasure of togetherness, the family regathering from far places, old friends joining forces again and new friends being welcomed. When I think of the cascade of people I have ridden the river with, my entire life passes in front of me. And the craft mark the passages: inner tubes and johnboats, kid-friendly and cheap. Canoes for campouts and twosomes. As the parent of youngsters, big rubber rafts for ultimate safety. Nowadays, a rented kayak for spontaneous, fuss-free day excursions. With newcomers, my family used to have an initiation ceremony that involved bowing to the gods of the river and chanting, “Owah tagu siam” repeatedly until the prank became clear. But nowadays we mainly just ask about food preferences and keep an eye out for incompatible personalities among the invitees.

Second Shoal: Catastrophe

“Have they found the drownt boy?” is the refrain of Art Homer’s 1994 book The Drownt Boy, published by the University of Missouri Press, a dark memoir of a difficult float trip down the Current in high water and an equally difficult childhood in Reynolds County. It’s a reminder that catastrophes happen on floats. People break bones. They drown. I once walked with friends to the scorched place on a gravel bar where a husband and wife had been killed by lightning the day before, just yards from shelter. We studied the spot and discussed what the couple should have done differently, quietly avoiding the fact that any one of us could have suffered the same fate.

Of course, the drunk and the careless get more than their share of trouble. But catastrophes happen even to the most cautious among us, and one hopes mainly to avoid the ultimate ones, like drowning or being shot by an angry landowner, as happened on the Meramec a few years ago. Rationally, we know that the most dangerous part of a float trip is the drive to the river. Even so, the thought lingers: Things go wrong. Floating the placid Huzzah with my wife, Sharon, a few years ago, we bumped an underwater log, which momentarily pushed us sideways. Nothing to worry about. But the tail of the boat caught the current, and in the blink of an eye we swept toward a jutting stob that, had she not ducked instantly, would have struck her in the chest with the full force of two bodies and a canoe. We shuddered, exchanged looks and floated on down.

In my novel The Language of Trees, one of the characters commits the ultimate act of foolishness. He imagines he can master the river. He builds a dam across the St. Francis, high upstream, to power his mining operations. And when the river breaks through — as rivers always do — the flood nearly destroys a village downstream. This incident is loosely based on an actual dam and an actual mine, though the final calamity is my invention. Children still swim, as I did, in the cool waters below the remnants of the Silver Mines dam, oblivious to the history that gave them their fine swimming hole.

What else is there to do with catastrophe, besides anticipate as best you can, brace yourself, try to duck and deal with the consequences? Even the best paddlers dump their boat now and then. I wrote an entire novel in graduate school, before I knew what the heck I was doing, and handed it to a trusted friend to read. The stricken look on his face a few days later, when he returned the manuscript, told me all I needed.

Take-out

Take-out

Eventually, one rounds the final bend. The take-out point lies ahead, the current always a little swifter than you would like, making for one last scramble to the bank and a fresh shoeful of gravel. And the emotion is always mixed. There’s satisfaction, of course, for few pleasures match a completed float, with dry clothes waiting in the car and a meal ahead. But also unfulfilled anticipation. What shall we do next time? A different stretch of river, or perhaps a spring float, or one in the late fall? Who needs an invitation next time? Or maybe it’s time for a solo trip, just one or two people on a new and lonesome stream.

I felt the same way when I published my first “real” novel, my first honest-to-goodness novel, in 2012, at the age of 56. The act was complete, and yet it was not. The successful completion of one trip only spurs the longing for the next.

But perhaps other stories await instead. The last time I floated the Black River down from Lesterville, I noticed a little plaque on a tree just below the junction with Peola Branch. It bore a man’s name, and I surmised that the spot was an ash-scattering place for someone who, like me, had found his own personal blessing in a spring-fed, cool-running river. “At the river forever,” it said, and I couldn’t envision a better fate.

About the author and publishers: Steve Wiegenstein, BJ ’76, MA ’82, PhD ’87, is a 2021 PEN/Faulkner finalist for his short story collection, Scattered Lights (Cornerpost Press, 2020). Phillip Howerton, PhD ’11, and Victoria Howerton, BA, BJ ’89, MA ’01, are co-owners and editors of the press.

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.