Sept. 8, 2021

Contact: Kenny Gerling, gerlingk@missouri.edu

Unless you attended the University of Missouri before the 2000s, chances are you haven’t heard of Dunklin House — the name of the bottom floor of Graham Hall. Although floors are no longer called “houses” and you can’t find Dunklin House on a university map, its legacy of accessibility is still being felt across campus decades later.

In 1961, Dunklin House became one of the first residence hall floors on campus designed to be accessible for students with disabilities. It was a development that came long before legislation such as the Americans with Disabilities Act (1990) made equal access commonplace at every university. It’s also just one of many groundbreaking milestones in Mizzou’s history of accessibility, which begins in the 1920s and continues to the present day.

In honor of Disability Culture Month, Show Me Mizzou talked with several former residents of Dunklin House. What follows is a small snapshot of a much larger story — one that explores Mizzou’s almost century-long long tradition of accessibility.

Before and after

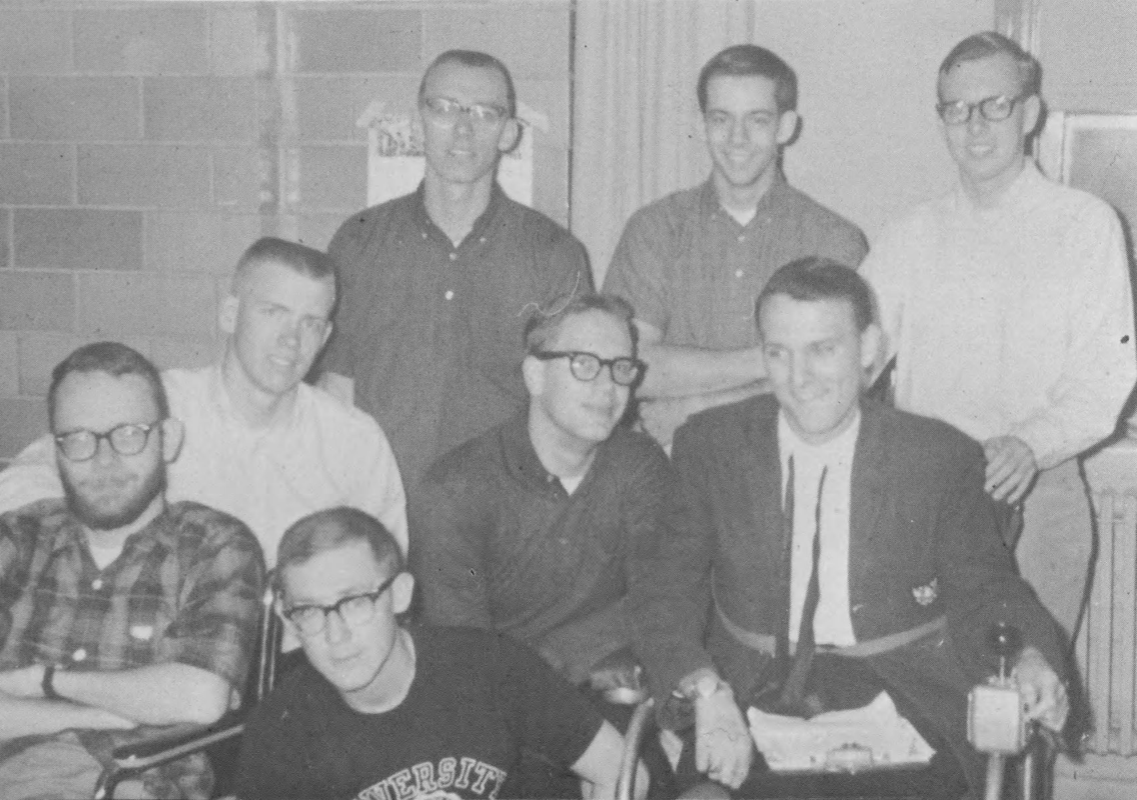

When Art Christie moved into Dunklin House in 1960, he said it was a floor like any other across campus. A year later, though, when he returned after the summer of 1961, Christie said he found a new ramp, rails, a water fountain, a phone booth, modified bathroom space and a door where a north-facing wall used to be. A new era had begun, even if life in Dunklin House went on mostly as normal.

“It was no problem whatsoever integrating men with disabilities into our mischief,” Christie said.

Christie’s roommate at the time was E. Richard Webber. Now a longtime senior district judge for the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri, Webber survived a severe tractor accident when he was 12 and credits a visiting nurse with telling him about a state program that could help with both medical bills and a scholarship to Mizzou. He eventually made it to Columbia in 1960 and, after first being assigned another residence hall, was ultimately moved to Dunklin House. It was the beginning of what he called “a real brotherhood.”

“No one considered it a special unit for students with disabilities,” Webber said. “It was home to us, and we got along with each other very well.”

History of accessibility

Mizzou’s history of accessibility largely begins with student veterans who were wounded during World War I. Once on campus, they established the Disabled American Veterans of the World War, one of the first organizations for students with disabilities in the country. As more students with disabilities sought out higher education, Mizzou continued to expand facilities to accommodate their needs. By 1968, archival documents show that Graham, Stafford, Cramer and Johnston Halls had more than 30 rooms to accommodate both male and female students using wheelchairs.

Around that time, MU was one of just three accessible universities in the Midwest. It was also named a designated education center for students with disabilities from Missouri and six surrounding states.

“It’s like there’s this secret history of Mizzou because no one knows about it,” said Amber Cheek, the current MU director of accessibility and ADA coordinator. “It’s not that we were perfect, but we can always be aspiring to create that next level of access — and we have more momentum for that when people know more of the history.”

Ahead of its time

Dunklin House included students with disabilities among the rest of the residence hall population — an approach Cheek described as “unique for the time period.” This configuration made it easier for students, both with disabilities and without, to interact and participate in campus life together.

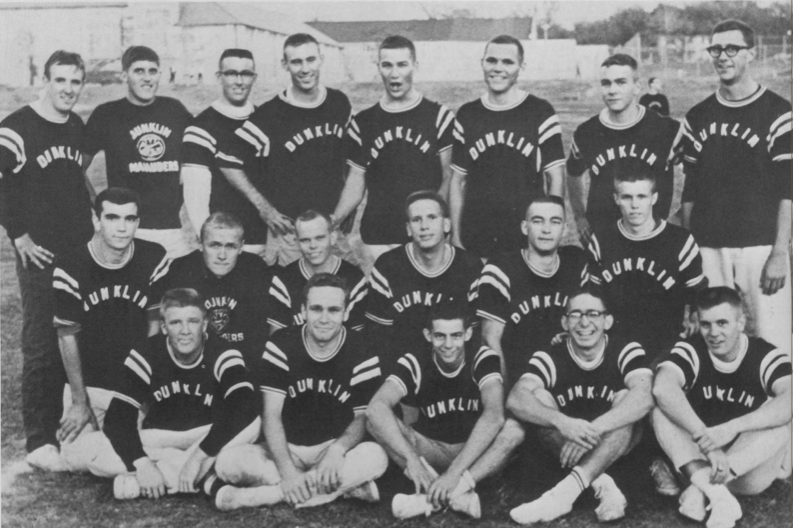

Joe Hoeddinghaus — a retired journalist, 1966 MU School of Journalism graduate and Dunklin House resident — said sports (particularly football) played a key role in the Dunklin House community. “We’d carry guys’ wheelchairs to the field because they couldn’t get there well through all the high grass,” he said. “We’d try to make everyone part of it.”

Lindell Dunivan, a fellow Dunklin House resident, graduated in 1966 with a degree in education and then later with a law degree in 1983. Dunivan said he came to Mizzou through a state program for people with disabilities seeking further education. He remembers his peers’ shared interest in intramural sports (and a particular rivalry with Fletcher House), as well as some of the unexpected perks of Dunklin House living. “I remember one person was diabetic and needed insulin daily, so he had a refrigerator,” Dunivan said. “That made him very famous around Dunklin House.”

For some residents, living in Dunklin House was their first introduction to issues of accessibility. “When I went to Mizzou, that was probably the first time I saw a wheelchair ramp,” said Al Akerson, a retired journalist and 1967 J-School alum who lived in Dunklin House at the same time as Christie, Dunivan, Hoeddinghaus and Webber. “In hindsight, if they’d told us about it, it would have engendered a lot of pride.”

Accessibility today

Definitions of accessibility have expanded since the time of Dunklin House. “Last academic year, we had 1,700 students connected with our office, and 90% of those had non-apparent disabilities (such as ADHD, mental illness and chronic illness),” said Ashley Brickley, director of the MU Disability Center. “We are seeing more understanding of how the classroom environment creates barriers for disabled students, so we’re looking at ways to reduce or eliminate barriers, allowing students to show their true potential.”

Sophia Martino is a senior human development and family science major and president of the Mizzou Disability Coalition, a student organization that promotes awareness and advocates on behalf of Mizzou’s disabled community. Martino says she and her group continue to work with the university to identify barriers to accessibility.

“When you think about accessibility, you may think about wheelchairs, or someone using a walker, or if they need a ramp, but it’s morphing into something different,” she said. “Now, it could include anyone who has bad anxiety or depression, or sensitivities to light and sound. It’s not just physical barriers, it’s equal access for everyone no matter where you are or who you are.”

Martino said she’s interested in possibly planning events to celebrate the history and impact of past students with disabilities on the campus community. “We’ve been talking about maybe having alumni come back for Homecoming, or do something like a Zoom call,” she said. “It’s cool to hear what their experience was like and how much has changed.”

September is Disability Culture Month on Mizzou’s campus, and there are plenty of ways to get involved and celebrate. Check out a full schedule of events and find more information on the Disability Center website.